Mobileground India: The Chinese invasion

The first wave of internet businesses may have belonged to America, but China's startups and investors are now leading the wave to dominate the mobile internet in developing markets. What does this mean for India?

Illustration: Smaeer Pawar

Illustration: Smaeer Pawar Investor Venky Harinarayan is that rare raconteur whose storytelling flourish is led by what the data shows. In late 2017, the founding partner of venture capital firm Rocketship.VC, who lives in Saratoga, California, spotted something about India. His team had been monitoring apps that were growing quickly in India, a year after 4G data prices had dropped to record lows. “We just woke up and said, ‘What the heck is going on here?’,” Venky recalls.

“We’d pick up the phone, make contact (with the app headquarters), and call these guys. Three or four in a row, we got companies from China.”

On January 12 last year, he wrote as much on online Q&A platform Quora, when asked about data-driven surprises. “Let me talk about the biggest surprise we have seen: The rise of the global Chinese start-up,” he wrote. “They are building products that are aimed at the world, not China. In particular, we were surprised to find Chinese app-makers focussed on the Indian market and having a huge success.”

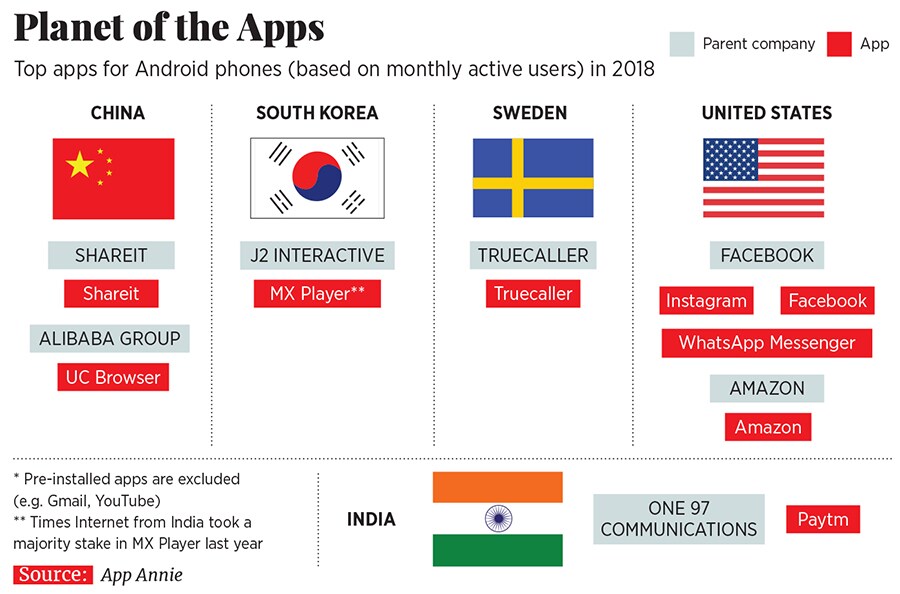

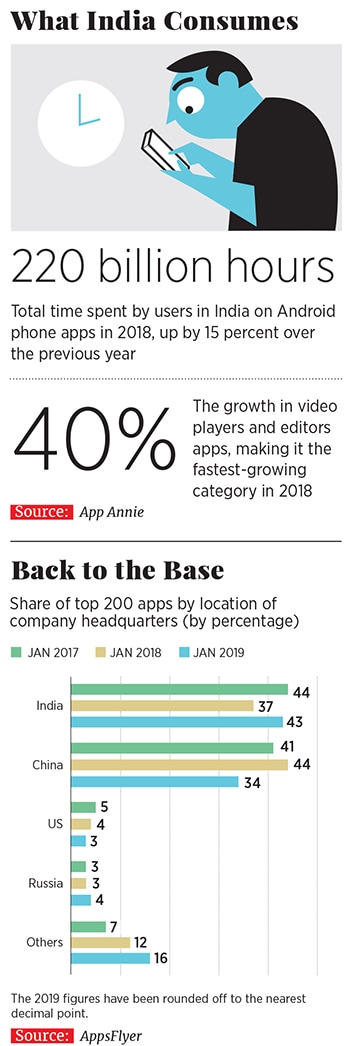

The 2017-18 trend in India came up on another radar of American origin: AppsFlyer, a mobile marketing measurement tool to track users. Mobile app advertisers and developers in India use AppsFlyer’s software development kit to track the effectiveness of their ad-spends. Every year, AppsFlyer tracks the top 200 apps in India. “If you looked at the total number of installs happening in India, 60 percent were from China, America, and the UK,” says Sanjay Trisal, country manager of AppsFlyer India. “On AppsFlyer’s platform, nearly 50 percent of the apps tracked in India in 2017 were originating from China.” he adds.

Here is the exact share of the top 200 apps in India. In January 2017, China’s share was at 41 percent, just behind India (44 percent) but well ahead of the US (5 percent). A year later, it increased to 44 percent, with India dropping to 37 percent, and the US apps share too falling marginally. This January, the share of the apps originating from India recovered to 43.5 percent, with China’s share just under 35 percent.

Venky was on point. In a call from the US, he says: “The first run of the internet apps was won by web services from America—Google, Amazon, Facebook—which have morphed into the app era. But they are not as rampant in this next wave (mobile) as the Chinese apps are in the emerging markets.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Venky Harinarayan, the founding partner of venture capital firm Rocketship.VC, says India is on top of the list for Chinese entrepreneurs

Venky Harinarayan, the founding partner of venture capital firm Rocketship.VC, says India is on top of the list for Chinese entrepreneurs