Naveen Patnaik's two decades, and counting

As Odisha CM Naveen Patnaik completes 20 years in office, the state government is scripting another chapter in a series of developmental programmes for the state, this time focusing on knowledge-based industries and manufacturing

An iron ore mine in Kheonjhar district. The government is now aiming to earn more from its rich mineral deposits, and not merely statutory dues

An iron ore mine in Kheonjhar district. The government is now aiming to earn more from its rich mineral deposits, and not merely statutory duesImage: Adam Ferguson / Bloomberg Via Getty Images

Odisha was in darkness when the world was celebrating the dawn of a new millennium in 2000, says R Balakrishnan, an IAS officer who was then posted in Odisha. A cyclone had uprooted electricity poles and millions of trees; it had destroyed homes, swept away entire villages and killed over 10,000 people. In the preceding years, the parched district of Kalahandi in south-west Odisha had become globally infamous as a symbol of starvation, malnourishment and poverty. It was under these circumstances that the state had elected Naveen Patnaik as chief minister (CM). A man who, until then, had lived in the US, written three non-fiction books, and was a reluctant inheritor of the political legacy of his father, Biju Patnaik.

“People’s self-confidence was at its lowest when Naveen Patnaik took over. The rest of the country bracketed Odisha as a backward state suffering from starvation, poverty and natural calamities,” says Balakrishnan, now an advisor to the Chief Minister’s Office (CMO). “In the last 20 years, breaking those stereotypes has been this man’s greatest achievement.”

At 74, Patnaik is today one of the longest-serving CMs in India. Through consistent welfare schemes, a clean governance image, sidestepping controversies and following development narrative, his party Biju Janata Dal (BJD) has defied anti-incumbency and people have re-elected him for five consecutive terms. In the 2019 Assembly elections, the party secured 113 out of 147 seats; the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was a distant second with 23 seats.

Patnaik commemorated 20 years in office on March 5. In an exclusive interaction with Forbes India at his residence in Bhubaneswar, he admits that the longevity of his tenure has helped sharpen his focus over the years. An important principle, he says, is to consider winning elections as just a byproduct of the work that a party is supposed to do for people.

He has now started planning ahead, which is evident in the first political appointment he has made after being re-elected as party president for the eighth consecutive term. In March, he elevated Pranab Prakash Das to the post of organisational secretary, which means the 45-year-old Jajpur MLA will be second-in-command after the CM on taking decisions about the party’s organisational affairs. Patnaik, however, continues to dismiss talks of succession planning, maintaining that “the BJD’s successor will be chosen only by the people”.

“When we came to power 20 years ago, the state was known for its bad disaster management, high poverty level and corruption. We have now set global benchmarks to handle disasters, have lifted 8 million people above the poverty line, and are known for our transparency,” he says. His vision for the next few years, Patnaik explains, is to “take Odisha to the next level”.

What he means is that besides concentrating on the minerals that the state is rich in, the BJD is setting ambitious new benchmarks to push tourism, heritage and sport. A step further in this plan of action will be to diversify and remodel Odisha as a destination for knowledge-based industries like technology and financial services; or, as certain senior officers of the CMO call it, “creating policy measures for the new world economy”.

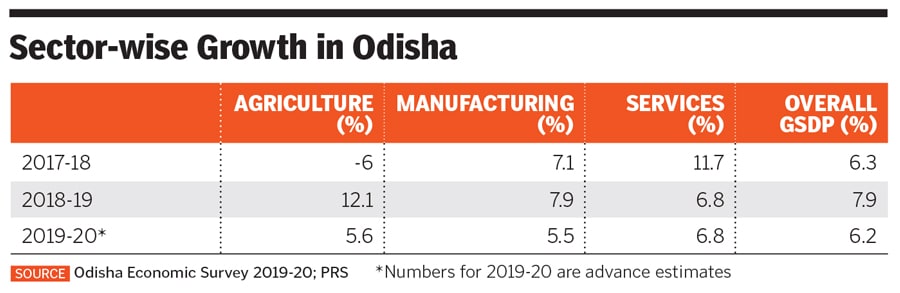

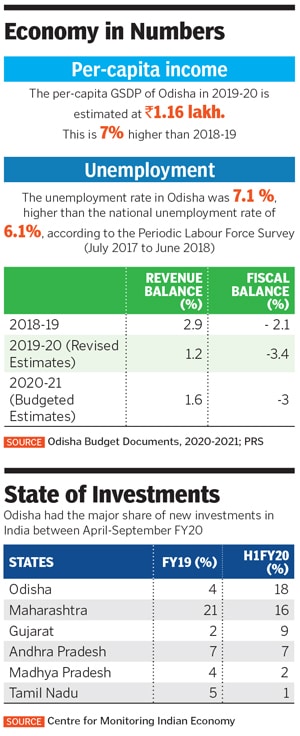

The state budget presented in February pegged Odisha’s Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) for 2019-20 at ₹533,822 crore, an increase of 7.7 percent over the previous year. The budget estimated a revenue surplus of ₹9,509 crore in the next financial year. According to Patnaik, the renewed focus on industry and manufacturing is expected to add further impetus to Odisha’s revenue generation capacity.

Naveen Patnaik, Chief minister, Odisha

Naveen Patnaik, Chief minister, OdishaIntent on industrialisation

Experts believe that Odisha needs to leverage its rich mineral assets to strengthen its manufacturing backbone instead of just becoming a raw materials supplier. The state has enviable coal, iron ore (accounts for more than 50 percent of the total production in India) and bauxite deposits, along with a long coastline.

Gyanranjan Swain, political analyst and assistant professor at Ravenshaw University, Cuttack, adds that the government’s push toward industry has intensified only over the last 15 months. The reason for the “delay”, according to him, is that for many years after the BJD’s 2000 win, its priority areas had mostly been mitigating natural disasters and consolidating power through flagship welfare schemes like food subsidies that distributed rice at ₹1 per kilo.

“Somewhere along the way, many crucial industrial deals just fell through,” says Swain, pointing to how the South Korean steelmaker Posco pulled out of a memorandum of understanding with the Odisha government to set up a 12-million-tonne capacity steel project in Jagatsinghpur district in 2017, following public resistance and regulatory hurdles. The deal, worth $12 billion, was the biggest foreign direct investment in India at the time. There was also Vedanta’s ₹50,000 crore aluminium project in Lanjigarh that struggled due to the lack of availability of raw materials like coal and bauxite on time.

“Most problems [with execution of industrial projects] happened because the government lacked negotiation skills and could not strike a balance between the needs of the local people and the companies,” says Swain. “But in the last one year, the government has adopted a remarkably different, holistic approach, where it seems to focus not only on industry, but also on policies for education, job-creation and health care.”

The state also has drawn up the numbers to back its intent. The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) stated that during the April to September or the H1 period of FY20, Odisha received an 18 percent share of all fresh investments across states, the highest in the country, followed by Maharashtra at 16 percent. This was a jump from the meagre 4 percent share Odisha had cornered in FY19. A report by Care Ratings pegs the aggregate value of fresh investments received in H1FY20 at ₹1.9 trillion.

After coming back to power last year, Patnaik sought to reinvent the state’s Industrial Policy Resolution, 2015, to unveil a new legislation that focussed on drawing fresh investments and boosting job creation. In the run-up to the annual Make in Odisha conclave to be held in November, he is planning new townships in the industrial regions of Kalinganagar, Jharsuguda, Paradeep and Angul-Dhenkanal.

In early March, the CM also inaugurated 23 new industrial ventures in the state, which he claimed will employ over 9,100 people. He launched three projects at the time—a solar power plant of Aditya Birla Renewables in Boudh, a vegetable oil manufacturing unit of AKM Agro in Khurda and the expansion of Jindal Stainless Limited’s (JSL) cold rolling unit in Jajpur—collectively worth about ₹709 crore.

(From left) Girls from the Dongria tribe study at a government ITI college, while others attend the Skill Enhancement Workshop at Chatikona village in Rayagada district

(From left) Girls from the Dongria tribe study at a government ITI college, while others attend the Skill Enhancement Workshop at Chatikona village in Rayagada districtImage:Vipin Kumar / Hindustan Times Via Getty Images

“The Odisha government is showing a renewed interest in handholding businesses and is trying to speed up its thinking to be in line with other leading manufacturing hubs. The bureaucracy is working hard to change the image of the state,” says Vijay Sharma, director, JSL.

The Delhi-headquartered company has made a total investment of about ₹10,000 crore in Odisha, and believes that while the detailed and transparent policies of the state instil confidence in investors, the government will continue to work on improving ease of doing business, take quick decisions, and improve the supply and demand-generation ecosystem.

Patnaik claims that Odisha “tops the country in spending sanctioned funds across various sectors”, primarily agriculture, rural housing, sports and skilling, countering the BJP’s allegations that the state government does not spend funds released by the Centre. “Odisha was a rice-deficit state when we took over, and now we are the third-largest contributor to the Public Distribution System in India,” he says.

While capital Bhubaneswar has been hosting a number of international events in hockey, tennis, football, rugby and athletics, as far as skilling is concerned, the state has reportedly trained 1.1 million people between 2014 and 2019, excluding engineering colleges and other higher education institutions, according to Mindtree Co-founder Subroto Bagchi, chairman of the Odisha Skill Development Authority (OSDA). It aims to train 1.5 million more youth in the next four years.

Odisha has earmarked nearly ₹1,400 crore to build a World Skills Centre to attract potential employers. “People get surprised to know that the Software Technology Parks of India [an autonomous society under the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology] reports more exports from a 10 km-radius in Bhubaneswar alone than from Delhi,” says Bagchi.

In the next few months, Bagchi will spearhead a Skill Vision, Strategy and Implementation Plan for the state, which will “predict where the world might be in 2030, what are the opportunities and discontinuities, how these will impact the notion of work, employment and entrepreneurship; and drawing from that, what preparedness do we need to build at a policy and implementation level”.

To bridge the gap between skilling and industry requirements, the OSDA has set up Centres for Excellence in areas like artificial intelligence, augmented and virtual reality and Internet of Things.

Beyond mining

Minerals and metals have conventionally been Odisha’s biggest revenue generators, and senior officials admit that the government was getting a raw deal by just collecting statutory dues (like royalty, taxes, contribution to district mineral funds etc) from mining operations. “Miners, on the other hand, were earning supernormal profits,” says an official close to the CM.

So mining companies whose leases expire on March 31 participated in an auction where the government invited online bids through the tendering process. The technically qualified bidders quoted an initial price offer, which is the percentage of premium/revenue to be shared with the government. The final amount is calculated on the basis of the sale price of the mineral as prescribed by the Indian Bureau of Mines.

“We received a revenue sharing premium as high as 95 percent. So if the market rate of the mineral is ₹100, the government will get ₹95. This is over and above the regular statutory dues. A mineral-based industry with value addition is our biggest hope,” the official explains. “With mining alone, we stand to earn ₹15,000 to ₹20,000 crore annually. This revenue will help us diversify into other businesses in the new world economy.” In that sense, the official adds, it’s like a hedge to move beyond mines, minerals and power, which are environmentally unfriendly businesses.

Senior journalist and political analyst Rabi Das cautions that while many of Odisha’s mining operations have affected the local people—who are vulnerable tribals in most cases—the new auction process that classifies entire mineral blocks for specific end users might push away smaller standalone miners. “Ideally, the government should have conducted a capacity analysis to see how the mining activities will burden the respective districts, the tribals and local players,” he says.

While the government increases its revenue, whether the bidders will be able to sustain and scale operations by paying high premiums remains to be seen. Businesses, however, seem to be looking at the bright side. In an interview with The Economic Times in February, Sajjan Jindal, chairman of the JSW Group that bagged four iron ore mines by bidding a premium as high as ₹132 for every ₹100 of ore produced, said he will be able to “afford high premiums” since having control over more than a billion tonnes of iron ore reserves will eventually turn the economics in favour of the company. JSW declined to comment on Forbes India’s queries.

ArcelorMittal bagged an iron ore mine in the Keonjhar district of Odisha with estimated reserves of 179.26 million tonne in the recent auction.

Operating in the state for over a decade now, the multinational steel manufacturing corporation also has a 6 million tonne pellet plant in Paradeep, and is working to double it production capacity. “Our Odisha facilities are crucial to ArcelorMittal Nippon Steel [AM/NS] India’s steel operations as they meet almost 50 percent of the company’s pellet requirements,” says Dilip Oommen, CEO, AM/NS India.

According to him, apart from rich natural resources, working in Odisha’s favour are its deep draft ports, road and rail connectivity, and availability of reliable power. “The government is also supportive of strategic investments in the state,” he says.

Politics behind the policies

Patnaik calls his father a pioneer who inspired him to think differently about governance and the potential of industrialisation. In the late 1990s, following his father’s demise, Patnaik was asked by then prime minister IK Gujral to contest from his Parliamentary seat in Aska.

Then in his 50s, Patnaik was perhaps the only second-generation politician in the country to not have been groomed for politics by his family, and was not even fluent in the local language Odia. When he broke away from the Janata Dal to form the BJD, he initially won general elections in alliance with the BJP, but broke away in 2008 following communal violence against minorities in Kandhamal.

The CM believes that the current communal unrest seen in Delhi and other parts of the country has only “further reiterated his decision to not ally with the BJP”. He says, “Lack of jobs leads to a great deal of frustration among the youth and I see this [communal unrest] as a reaction to that.”

While he has refused to incorporate the National Population Register (NPR) as part of the Census process that will start in April and will follow the 2011 format, he supports the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) since it “only deals with outsiders”.

Analyst Das believes that Patnaik has remained in power for the last 20 years because “while there are no local leaders within or outside his party who match his level of charisma and popularity, he steers clear of commenting on national political controversies. He supports the Centre on key political issues—the scrapping of Section 370 in Kashmir, for example—which is why the BJP views him as less of a threat”.

The appointment of Pranab Prakash Das as the BJD’s organisational secretary reiterates how Patnaik has been testing the waters for the party’s future by letting young party workers, bureaucrats and officers take charge, the analyst believes.

A similar example of trusting young officers could be seen through Patnaik’s ambitious Mo Sarkar initiative to reduce red tape across all levels of state departments, and the Integrated Financial Management System that will take all government transactions online. The latter is expected to be rolled out for the next financial year.

Steering Mo Sarkar and the 5T (Teamwork, Technology, Transparency, Time leading to Transformation) initiative is 45-year-old V Karthikeyan Pandian. The IAS officer says the government’s strategy primarily involves collaborating with stakeholders across various areas of expertise. “Apart from Bagchi, we have Sopnendu Mohanty from the Monetary Authority of Singapore helping to build financial services systems, and various professionals, including Public Health Foundation of India’s K Srinath Reddy, providing insights on health care,” he says.

Patnaik considers his work in encouraging women’s participation across various levels of politics, and legislating for their education and health care as one of his major achievements in the last 20 years. “In a democracy, where you have to win over people’s trust every five years, the government in power is often known to undo the work of its predecessor,” notes Balakrishnan. “The sheer continuity of his tenure has helped Patnaik reshape the development narrative of Odisha to an extent that no other party will be able to reverse his work or overturn his legacy in the future.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)