NBFC crisis: Running on empty

Half a decade of slowing demand, regulatory changes and tight financing have taken the real estate sector—and those lending to it—to the brink of a shakeout

Mumbai is estimated to have nine years of inventory left and the number of units that may never be constructed runs into tens of thousands

Mumbai is estimated to have nine years of inventory left and the number of units that may never be constructed runs into tens of thousands

Image: Ele Rein / Getty Images

Ten minutes into our conversation, Khushru Jijina’s warning jolts us. “The truth is that you will see a lot of projects lying unfinished,” says the managing director of Piramal Capital and Housing Finance. “Thanks to consolidation, there are several developers doing well whereas some are in distress,” he adds. He’s well placed to know. After all Piramal has ₹38,700 crore lent to the country’s developers and Jijina admits that he’s recently taken a close look at his loan portfolio. Visible from the conference room of the Piramal Capital offices in central Mumbai is the outline of a vast decade-long project—the Lodha World Towers. It’s Exhibit A of a decade that saw inflating asset prices that investors piled up, based on the Greater Fool theory (there’s always a sucker around the corner willing to pay a heavy price). Circa 2018 we’re left with slow user demand and an overleveraged industry grappling with a changing business model.

The last five years have seen India’s home builders hurtle from one crisis to another. Each time they’ve kicked the can down the road and borrowed money to stave off the inevitable. As a result, most developers survived on what can at best be described as an oxygen mask of money at high interest rates. There is every indication now that this mask is being pulled off all but the very best. Jijina’s second prediction is that only 10 percent of developers, who have a clear focus on execution and sales, will survive.

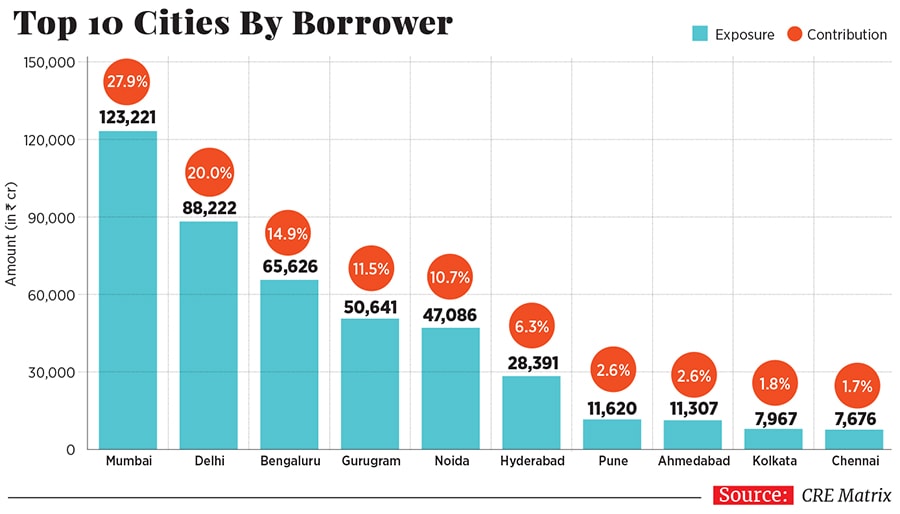

The length and severity of this slowdown has confounded even the most ardent optimists that Forbes India spoke to. Let alone predict the next upcycle, they acknowledge that they’ve consistently picked the bottom incorrectly over the last three years. Over the last decade the leverage in the sector has increased from about ₹125,000 crore to ₹500,000 crore according to a cross section of industry professionals. The result: An industry that is up to its neck in debt with cash flows that have dried up and limited their ability to service the debt.

Which way the cookie finally crumbles decides who—the buyer, the developer or the financier—escapes with the smallest haircut. “It is not fair for lenders to insist on such quick deleveraging. The sector has slowed down and everyone has to accept reality,” says Sudhin Choksey, managing director of Gruh Finance, an HDFC subsidiary.  Jijina’s counterpart at Kotak Investment Managers, S Sriniwasan, points out that, “There has to be a complete restart in this business with well capitalised developers who have financial discipline.” The silver lining is that this once-in-a-generation shift in the business model is likely to result in a lot more efficient industry—one with moderate but steady price appreciation. But first a look at how we got here.

Jijina’s counterpart at Kotak Investment Managers, S Sriniwasan, points out that, “There has to be a complete restart in this business with well capitalised developers who have financial discipline.” The silver lining is that this once-in-a-generation shift in the business model is likely to result in a lot more efficient industry—one with moderate but steady price appreciation. But first a look at how we got here.

A Once-in-a-Generation Boom

The half decade-long real estate boom from 2003 to 2008 meant that the industry and buyers both ceased to remember what a downcycle looks like. Industry executives look back not too fondly to the days when a new generation of swashbuckling fund managers deployed millions of dollars in projects from Guntur to Mamallapuram, and realty developers never missed a chance to flaunt their Armani and Ermenegildo Zegna suits. At industry association conferences, no expense was spared with developers, brokers and at times high net worth clients being flown to some of the most expensive hotels in the world. Seven-star The Atlantis in Dubai was a favourite. Those were the days when anyone who owned a land parcel or had built even one building called himself a real estate developer.

In the 2000s, the idea of building a project was simple. Landowners (developers) would take money at high rates (18-20 percent) to get permissions. With the approvals in place the business was one with negative working capital. Here’s how: Developers would launch projects aggressively and the money raised through initial sales was used to start the project. Once the basic structure was complete the developer would have collected 90 percent of money from buyers but would have spent only a third. The rest of the money was diverted to buy land parcels elsewhere. The cycle repeated itself across projects. With the market booming and projects selling out within days of launch, it turned out to be a virtuous circle.

As land prices skyrocketed, most developers paid exorbitant amounts to acquire these parcels. The initial sales came from investors who wanted their fingers in the lucrative pie of Indian real estate; the exuberance resulted in developers losing sight of the end customer and building homes for which there was little end-user demand. Exhibit A mentioned earlier is a good example. Greater Noida, where there are no takers for constructed homes, is another. And then came the final nail in the coffin: The global financial crisis. It was also the time when Lehman did its last transaction in India by investing in Unitech Ltd’s Mumbai project in May 2008. Unitech, then the second largest developer by market capitalisation, now trades at ₹2 per share (down from ₹500) on the Bombay Stock Exchange.

And thus began the game of ‘passing the parcel’ of loans to each other. Developers were busy shifting loans from one lender to the other, seeking favourable terms and lenders rescuing each other and passing the baton. But, lenders and NBFCs now believe that this time around it may well be the end of the road.

In the absence of sales it has become crucial to tie up working capital. Demonetisation dealt a body blow, with investors who did a lot of deals with cash pulling out. Then came the Goods and Services Tax (GST) that levied 12 percent on under-construction projects. The Real Estate Regulation and Development Act (RERA) meant that developers had to put aside 70 percent of money collected in a project in a separate account. As capital turns scarce for developers the industry will move towards well capitalised players, like the large corporate houses.

“Globally real estate is a capital-intensive business and those with strong balance sheets participate in it. In India anyone with a land parcel could start development. With all these regulations coming into play and NBFCs becoming serious about who they will lend to, only developers with capital to see through the end of the project will be able to survive,” says Mahesh Singhi, founder and managing director of Singhi Advisors.

What Next

The debt-fuelled party of the last decade masked the fact that there is very little equity left in a large number of residential real estate projects. If the developer walks away from the vast majority of unfinished projects across the country or files for bankruptcy, he has very little to lose. It’s a point that Amit Bhagat, managing director at ASK PIA, has been making for over a year now. “The better known developers can still raise equity capital but the lesser known ones will need to find partners soon,” he says. Else there is a very real fear of projects not being completed.

Meanwhile, financiers have now turned wary. Ask any developer how life changed after September 6 when IL&FS defaulted and a shudder may well run down his spine. India’s government banks with lower than required capital found themselves in a position that forbade further lending. Their deposits were however sticky and had increased as a result of demonetisation. This resulted in a regulatory arbitrage and banks and mutual funds rushed to lend to NBFCs with their less stringent capital requirements.

According to a note by ratings agency Crisil on December 5, growth in assets under management of non-banks (NBFCs and housing finance companies) is expected to halve to nearly 9-10 percent in the second half of fiscal 2019 because of funding-access constraints, after clocking a robust 20 percent increase in the first half.

Commercial papers (duration one year or less) were used to raise money that was lent for longer tenures. With the IL&FS default, credit markets froze and the commercial paper rollovers became difficult. Developers who Forbes India spoke to said that disbursals stopped for projects where credit lines had been approved. The situation is slowly getting back to normal with NBFCs accessing longer-term wholesale bank loans. These financiers also admit that they are using this period to remove the weak performers from their portfolios. Tier 2 and 3 developers will find it hard to access credit even when the markets get back to normal.

With the introduction of RERA there are also stiff penalties for missing deadlines. “The business will now split up with three distinct categories—developers, financiers and land aggregators,” says Mohit Malhotra, managing director of Godrej Properties. A large number of listed developers are also unlikely to keep large amounts of land on their books as unlike pre-2008 the market has begun valuing companies only for their execution capabilities and not for their land parcels.

In the next decade expect a lot more joint development agreements between developers and landowners. In exchange for a fixed share of top-line the developer doesn’t have to lock his capital into buying land. Permissions are also mostly the landowners’ headache. Developers are responsible only for designing and marketing the project. Big brands like Godrej Properties, Larsen & Toubro and Shapoorji Pallonji have aggressively signed on projects in the past year. “We have a large holding and about a year and a half ago we did a check on what we can develop and in what timeline. We did a study across the country and found that one developer in one location cannot do more than a million square feet,” says Dharmesh Jain, managing director of Nirmal Lifestyle, which owns some of the largest land parcels in the suburb of Mulund in Mumbai. Going forward he plans to do only joint development deals. He won’t be the only one.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)