NEP 2020: Can India attract foreign universities?

The National Education Policy opens doors for foreign universities to set up campus in India—a policy that has long been in limbo—but its success depends greatly on the next steps of implementation

European fashion and design school Istituto Marangoni set up a campus in Worli, Mumbai, in 2017

European fashion and design school Istituto Marangoni set up a campus in Worli, Mumbai, in 2017Image:Courtesy Istituto Marangoni

Come August and each year, lakhs of teenagers across India get busy sorting out paperwork, brushing up on (microwave) cooking, readying for a series of teary farewells. In 2019 alone, more than 7.5 lakh students boarded flights to universities abroad—a staggering rise over the 66,000-odd of a decade ago.

While Covid-19 has put a pause on students’ plans to go overseas this year, this trend may not be deeply hit in the long term. As more and more students aspire for a foreign education, the new National Education Policy (NEP), announced on July 29, hopes to fulfil some of these dreams even while at home.

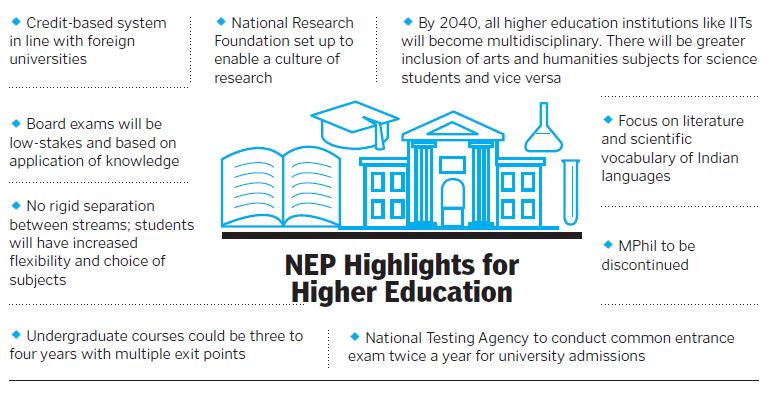

As per the NEP, ‘selected universities, for example, those from among the top 100 universities in the world will be facilitated to operate in India. A legislative framework facilitating such entry will be put in place, and such universities will be given special dispensation regarding regulatory, governance, and content norms on par with other autonomous institutions of India’.

This means that foreign universities, filtered via certain parameters, will be able to set up operations and campuses in India. The policy framework adds that credits acquired at foreign universities can be counted towards a degree within India, and that student and research exchanges will also be facilitated between Indian and global institutions.

The framework isn’t new; in fact, the UPA-2 government had introduced a detailed bill in Parliament a decade ago, called the Foreign Educational Institutions (Regulations of Entry and Operations) Bill of 2010. However, the Bill, then criticised by the BJP, saying it would increase the cost of education for students, eventually lapsed when the 15th Lok Sabha was dissolved. This component of the NEP is being seen as a reversal of that stance by the ruling party.

Back then, there were talks that A-grade universities such as Carnegie Mellon, Duke University and Georgia Tech, all from the US, were interested in setting up shop in India, apart from those in the UK, Canada and Australia. Others, including Canada’s Schulich School of Business (part of York University) and Italy’s Bocconi University, did open Indian campuses, but with no movement on the legislation, have had to operate with restrictions.

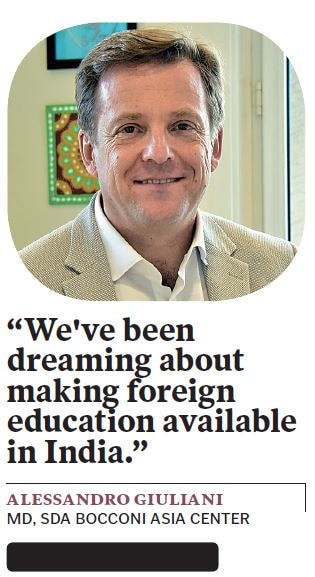

“We’ve been dreaming about making foreign education available in India, and actively pursuing that dream for the nine years we’ve had operations here,” says Alessandro Giuliani, managing director of SDA Bocconi Asia Center, an offshoot campus of the Italian business school that operates in Mumbai’s Powai. “The Foreign Education bill never saw it through to notification. So all this time, we have been delivering quality education within India, but haven’t been able to deliver degrees or diplomas. I hope that this time, this is seen through.”

To overcome this hurdle, Bocconi’s India students must take a final semester at the university’s main campus in Milan to acquire a diploma. Similarly, Schulich’s campus in Hyderabad, operated in partnership with the GMR School of Business, offers a two-year MBA programme, also with a twinning arrangement. Students study the first year at the Hyderabad campus, taught by faculty from the headquarters, and the second year in Toronto. The four-term MBA costs about $20,000 per semester, while MBA in India students are granted $10,000 in financial aid for the first year. At top-tier US universities, a year of tuition could set you back up to $60,000.

Like Giuliani, the director of the Schulich School of Business, India, Viswanathan Raghunathan, says he has long nurtured the thought of delivering foreign degrees in India—“but as of now, it is still only just a thought”, he says. “The stillborn Foreign Education bill yielded little result, and this document is largely silent on the way forward, except what one could garner from the interview of the Higher Education Secretary in the media.”

SDA Bocconi Asia Center, an offshoot campus of the Italian business school, operates in Powai, Mumbai

SDA Bocconi Asia Center, an offshoot campus of the Italian business school, operates in Powai, MumbaiImage: Courtesy SDA Bocconi

There is no word yet on if and when Parliamentary approval for foreign campuses in India will come through, so for all practical purposes, it is still status quo, he adds. “It seems that for now, one should remain satisfied with twinning programmes, which are already permitted under the norms of All India Council of Technical Education (AICTE)—albeit with many constraints and designed in an era where perhaps the intent was more to discourage than encourage such twinning,” he says. “Popping the champagne bottles on this account will have to wait.”

As Raghunathan points out, a lot rides on the actual implementation of the policy this time. “For example, try as I did, I could not find any yardsticks of measurement to assess the extent of success of the last National Policy on Education unrolled in 1986,” he says. “Were all parameters achieved? If not, how many? Who was accountable for which part of implementing the policy? Did any head ever roll for not successfully attaining the end-result? We do not know.”

Even so, experts agree that the advantages of inviting—and encouraging—foreign universities to have Indian campuses, are a no-brainer. “Not only will they catalyse the process of transforming our age-old education system, but will also help us retain good faculty talent in India,” says Sanjay Padode, founder of IFIM Business School, president at Vijaybhoomi University and chairman of the CDE (Centre for Development Education). “With enhanced collaboration between Indian and foreign universities, our standards of teaching, learning and the research process will rise; and of course, we can retain the forex outgo due to Indian students pursuing education abroad.”

Indian students have reportedly spent an estimated ₹40,000 crore each year on foreign education in recent years. For students who eventually intend to stay and work in India, the investment is not always worth it.

“I wanted to pursue a management course with an international curriculum, but to move abroad just for that, and eventually come back to India, didn’t make sense,” says Kaustubha Panda, a 2020 graduate of SDA Bocconi’s MBA programme. “The SDA Bocconi Asia Center ticked all the right boxes for me—allowing a global education in India. It offers perspective on both the Indian and European business scenarios, with a mandatory immersion in Milan.”

The study experience in India and Milan, says Panda, was similar. “It’s the same curriculum being delivered by the same faculty,” he says. “There was also an exchange term to Bocconi India, where students from partner B-schools visited for an exchange semester. This helped us immensely in creating a meaningful ideas exchange with international students.”

European fashion and design school Istituto Marangoni set up campus in India in 2017, in a posh Worli building. Its other campuses are in cities such as London, Paris, Milan, Florence, Shanghai and Miami. “With its cosmopolitan culture, vibrant cinema and burgeoning fashion industry, Mumbai was a natural choice to set up Istituto Marangoni’s first campus in India,” says Tarun Pandey, COO, Istituto Marangoni in Mumbai. “Our faculty consists of full-time staff from the European schools but also regular ‘flying tutors’ who come to deliver specialist units on the programme from Milan, Paris and London. To facilitate international exposure, the three-year programmes also offer students the option to spend their second or third year at our European campuses.”

Course Correction

The status quo for such foreign schools in India is riddled with regulation. For instance, Raghunathan of Schulich says that problems arise from the fact that the regulatory requirements almost exclusively focus on physical infrastructure—acreage of land, square-footage of built-up space, size of the canteen, library, computers per student and so on.

“A business school with 300,000 books and journals available online would not cut the ice,” he says. “But a school that meets the criteria of X physical books or Y journals per student or some such absurd number does. In applying these constraints, our regulations overlook the fact that top international institutions are successful back home because they are more technology and intellectual-capital driven—not so much by physical attributes or very large campuses.”

Another debated criterion of the Foreign Education bill was its limit on profit-making, and whether that would deter universities from entering India.

“I’ve been advocating that the education sector requires huge expansion, and therefore, huge investment. This cannot come only from the government,” says Sandeep Sancheti, vice chancellor, SRM Institute of Science & Technology, Chennai, and former president, Association of Indian Universities, New Delhi. “The private sector has to contribute, but it can’t run only on charity if we want world-class institutions. We don’t have large alumni capacity like other countries. We’ll need another model.”

According to Sancheti, India should encourage institutions to generate large corpuses, possibly with certain limits on taking that profit out of the country. “The education sector is struggling under Covid-19. Had we created corpuses and had reasonable savings, we would be in a better position,” he says. “Education has now become an industry, a commercial sector like any other.”

“One of the key reasons western universities set up foreign campuses is to increase their reach to students in other countries and generate additional fee revenue,” says Akhil Shahani, managing director, Shahani Group, which runs the Thadomal Shahani institutes.

“The reduction in international student applications to these university’s home campuses due to post-study work visa restrictions has increased this trend. As mid-tier universities depend more on student fee revenue than universities in the global top 50, it’s mostly these that set up international campuses in countries like Malaysia, Singapore, the UAE etc. Very few top 50 universities have opened foreign campuses as they feel it reduces the exclusivity of the home campus.”

Shahani refers to a vague mention in the NEP, which says that universities that will be allowed within India should be from the top 100 universities—it does not specify which such ranking it refers to.

“In the absence of other criteria we could look at ranks, but that can’t be the only filter,” says Sancheti. “Suppose I want to develop a university for the railways, or a new mining department, both dire needs for the country—these may not be in the world’s top 100. Moreover, we have to match our aspirations with our own capabilities. To give a crude example, think of it like someone looking for a life partner—your minds must meet, your purpose should match. If we restrict entry to the top 100, why would other countries invite partnerships with even premier Indian institutes, which don’t fall within that range?”

Universities, while interested in India’s market size and talent potential, will ‘take their sweet time’ to announce Indian campuses, as they would want to consider every aspect of potential operation here, says Sharad Mehra, CEO-Asia Pacific, Global University Systems (GUS), a network of higher-education institutions that aim to operate around the world.

“Universities will first look at what they get out of it—in terms of profit,” Mehra says. “For India, however, inviting such education will really expand the talent pool for MNCs and other big firms. Many institutes that have set up campuses in China, Australia and other locations will look at India as a potential market, but they will be clear in the terms of how they invest.”

Will this drive up the cost of education and accessibility for Indian students, as previously criticised by the BJP?

“Cost is not necessarily driven by one element. It’s driven by hundreds of elements in the market, the first of which is the need itself,” says Sancheti. “However, once quality is assured, the cost can be easily recovered. Moreover, technology, as it progresses, always flattens the cost. This is true for the internet, mobile phones, energy and so on. It’s a one-time investment—and yes, it may not reach the rural population initially, but with technology—and as we have seen with telecom—it will get there eventually.”

Finally, will this encourage fewer Indians to fly overseas for education?

This depends on the finer points of execution—which universities will enter; the quality of faculty; whether industry will deem a degree from the Indian offshoot at the same value as that of the main campus. Students seeking foreign education base their decisions on factors including the university’s reputation, tuition fees and scholarships, quality of the programme, and most importantly, post-study work opportunities.

In fact, with US President Donald Trump’s crackdown on work visas, the number of Indian students going to the US reportedly fell from 447,836 in 2017-18 to 209,063 in 2018-19, according to a reply by the HRD Ministry (now called the Education Ministry), which could be a good opportunity for Indian education. However, whether an offshoot campus can replicate the experience and exposure of learning in a foreign country, as well as the opportunities, remains to be seen.

“Students aspire to go to developed countries not only to get a world-class education, but also to get a first-hand experience of living in a more advanced foreign country and gaining highly valued international work experience,” says Piyush Kumar, regional head, South Asia, IDP Education, a study abroad agency. “In my opinion, the main campuses of the world's leading universities will continue to have their own charm.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)