Sugar industry: A cooperative time bomb

In Ahmednagar in Maharashtra, the heartland of the sugar movement, political whims and natural calamities have created a precarious credit situation

In Shrigonda taluka, the Sahkar Maharshi Shivajirao Narayanrao Nagawade Cooperative Sugar Factory stands deserted ahead of crushing season|

In Shrigonda taluka, the Sahkar Maharshi Shivajirao Narayanrao Nagawade Cooperative Sugar Factory stands deserted ahead of crushing season|Image: Mexy Xavier

Satish Shinde is one of those rare farmers who hasn’t taken an agricultural loan in the past couple of years. With some deft management, the 40-year-old resident of Dhanore village in Maharashtra’s Ahmednagar district has managed to turn things around for his seven-acre farm.

Shinde, who is a member of both the local credit society and the Vithalrao Vikhe Patil Cooperative Sugar (VVPCS) Factory, the first sugar cooperative in Maharashtra, has bank accounts at the State Bank of India, Yes Bank and the Ahmednagar District Central Cooperative (ADCC) Bank. Even as directions have been placed by the Reserve Bank of India on at least five cooperative banks in the past two years—the latest being on the Punjab and Maharashtra Cooperative Bank last month—he is fairly confident of his deposits at the ADCC. Instead, Shinde chose to withdraw his money from Yes Bank after he heard about the concerns over its ill-health.

The ADCC Bank has 1,484 Primary Agricultural Credit Societies affiliated to it and 287 branches across the district. The sugar cooperatives have been the backbone of the economy here, with farmers, sugar factories, cooperative banks and politics closely intertwined in the development of the region.

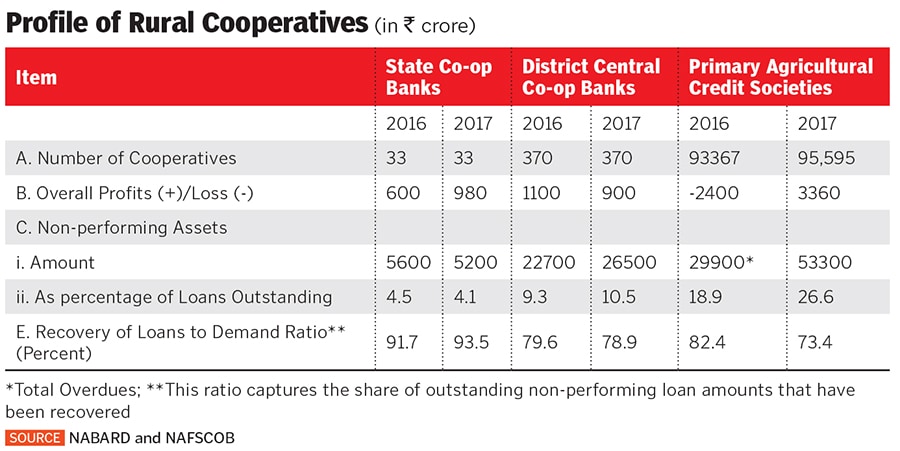

“Fifty percent of the economy here is related to sugarcane,” says Raosaheb Varpe, CEO of ADCC Bank, which finances the credit societies as well as gives loans to sugar factories. Farmers are members of the credit societies, while the societies and sugar cooperatives have to become cooperative bank members to avail loans. The third tier in the rural banking structure are the state cooperative banks, which are refinanced by the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD).

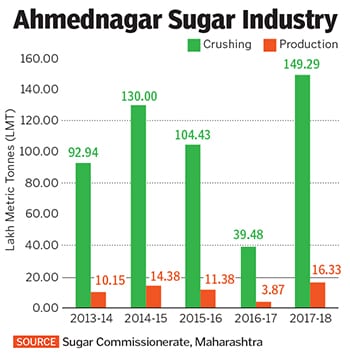

The ADCC Bank has a share capital of 237.84 crore with loans disbursed standing at ₹5,095.77 crore and profits of ₹37 crore in the financial year ended March 2019. “Ups and downs are part of growing the crop, and there is usually a cycle of one bad season every 5-7 years (see graph),” says Varpe. Last year’s drought in the region means there is not enough sugarcane crop for factories to open this season.

The Vikhe Patil sugar factory is likely to have just about enough crop to open for a couple of months this year as against the usual 5-6 months crushing season from November to April. While in Shrigonda taluka, on this day in early October, the Sahkar Maharshi Shivajirao Narayanrao Nagawade Cooperative Sugar Factory wears a deserted look. It is unlikely to open this year and no maintenance work is being done to prepare for the crushing season. A recently commissioned co-generation facility has gone through one trial and will function only when the factory reopens next season. Workers at the factory have been put on ‘lay-off’ mode, which means they will be paid only 50 percent wages. Most private factories lay off workers, with no wages at all.

Besides loss of income, lack of enough sugarcane means farmers would not have availed crop loans. And the factories will not need short-term loans to pay farmers for the crop and other expenses. Repayment of loans also takes a hit and credit societies are unable to pay interest to the cooperative bank. “For cooperative banks, it also means lower income because they have to invest their money elsewhere,” says Varpe.

The sugar sector, says Subrahmanyam Bhima, managing director of the National Federation of State Cooperative Banks Ltd, works on the whims of nature. “Good rains mean a bumper crop, more finance, repayment and profits. But drought means lesser crop, default, possible NPAs or restructuring.”

*****

The cooperative movement related to sugar is also subject to political whims. Elections to successive boards up the cooperative ladder, including in credit societies and banks, have been a natural route for founders of sugar cooperatives to power, clout and vote banks.

Former Congress politician and now BJP MP Sujay Vikhe Patil, whose great-grandfather founded the Pravara cooperative factory (now VVPCS) in Pravaranagar in 1950, has been busy all day with rallies held by Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis. We meet him late at night at Dr Vikhe Patil Memorial Hospital that the neurosurgeon-turned-politician runs along with other engineering and medical institutes in the region.

“When you’re running a sugar factory, there are farmers affiliated who are beneficiaries of the factory. They are also voters. So, for instance, when they supply sugarcane, they are usually paid in 15 days. But if I am chairman and he says there is a wedding in his house and requests for early payment, we help… and they see that we stand by them and offer a support system. In the end, you end up being a leader,” he says. The family has three sugar co-operative factories in the region of which it plans to open only one this crushing season.

Meanwhile, in an already-stressed sector, unpaid debts rise. While the long-term mortgage loans at the Vikhe Patil factory stand at about ₹82 crore, and other dues at ₹273 crore, the Shrigonda factory has loans to the tune of ₹55 crore and other dues of about ₹58 crore as of March 31, 2019, according to the annual reports.

One of the solutions to tide over the drought years has been to diversify. “Standalone factories taking only sugar crushing is risky for banks. But now co-generation of bio electricity, distillery, paper and particle units of sugar factory gives yield to sustain from the drought crises. In recent times, the government has been encouraging sugar units to produce ethanol instead of sugar which is being used as bio fuel,” says Bhima.

The Ahmednagar District Central Cooperative (ADCC) Bank has 287 branches across the district

The Ahmednagar District Central Cooperative (ADCC) Bank has 287 branches across the districtImage: Mexy Xavier

Vikhe Patil says banks should restructure the loans for factories that have been performing, been paying their dues and have no NPAs. “All banks under which these sugar cooperative factories function must be called for a meeting and the loans should be restructured with a repayment period of 15 years,” he says. “So you give the factories a chance to run and your money won’t be lost either.”

Meanwhile politics is playing out in a different way at the credit society level. Though some percentage of default by farmers is an intrinsic risk the credit societies function with, over the past two years, recovery of loans and interest has fallen drastically. Farmers have stopped repaying them in the hope of a loan waiver. The Maharashtra government sanctioned ₹24,000 crore for loan waivers of 51 lakh farmer accounts as part of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Shetkari Sanman Yojana in 2017. The amount was capped at ₹1.5 lakh per farmer on payment of the total outstanding loan. The waiver, however, did not benefit those who had regularly paid up their loans, according to farmers. “So people have stopped paying their loans expecting a loan waiver,” says a farmer on condition of anonymity. “Do saal se pack ho gaya hai (Things are at a standstill for two years),” adds Nilesh Pawar, secretary of a local credit society in Ghargaon village. “A total of ₹13 crore was distributed, but even 10 percent recovery is not happening.”

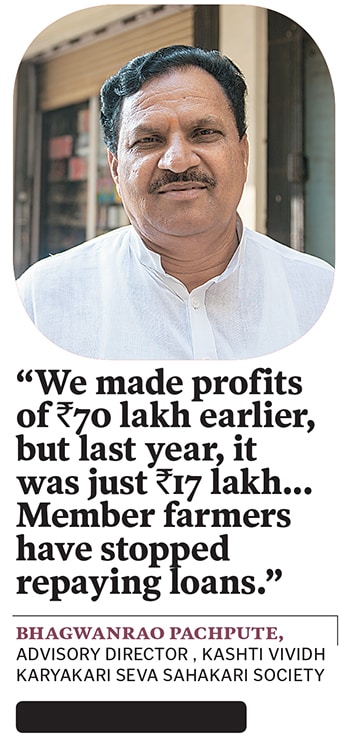

At the Kashti Vividh Karyakari Seva Sahakari Society in Shrigonda, which started a mall in 1981, years before malls became an urban feature, shops sell everything from consumer goods to grocery and textiles to shoes and medicines, all below MRP. The society initially functioned only as a cooperative credit society and then turned multi-purpose. “We made profits of ₹70 lakh earlier, but last year it was just ₹17 lakh,” says Bhagwanrao Pachpute, advisory director and ex-chairman of the society.

According to its annual report, while ‘member loan outstanding’ has gone up from ₹6.84 crore as on March 31, 2018, to ₹8.51 crore as on March 31, 2019, the interest received on member loans has gone down by almost 75 percent from ₹48 lakh in 2018 to ₹12.56 lakh in 2019. “Farmers have stopped repaying loans,” says Pachpute. With repayment at a standstill, it follows that no new loans are being disbursed.

“After the elections when there is no loan waiver, people will start paying. It will be slow, but it will start,” says Pawar.

Till then, the rural economy continues to pile up its debts even as founders of sugar cooperatives—whether they are contesting the elections or not—attend political rallies. “There is a saying in Marathi,” says social worker Amar Kalamkar, “Dev paavla nahin tar chalel, pan kopala nahin pahije [It’s okay if the Gods don’t bless you, but they should not unleash their wrath].”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)