Tech tools to teach children

Vineet and Anupama Nayar are betting $100 million that their low-tech tools will get students to learn in India's notoriously ineffective rural schools

A big part of the solution to getting young children to learn math in the poorest, most educationally backward parts of the world may be just simple items such as coloured rings on strings, plastic blocks of different sizes and multihued circles, triangles and squares. “The kids take a lot of interest when we use these things. They don’t see it as work then,” says Revati Mathyal, a teacher in a northern India school who’s working with a class of 16 students in a mix of grades one through five. “When we use traditional methods of teaching math, it takes time for them to understand. This is all so colourful and attractive.”

The strategy seems to be working. Before it was adopted, only 41 percent of second-grade students surveyed in Uttarakhand, the Himalayan state where the school is located, could do simple addition. This has now risen to 91 percent. Similarly, the share of students who can do simple subtraction jumped from 33 percent to 89 percent; for multiplication it went from 25 percent to 83 percent; and for division, 15 percent to 73 percent.

Vineet Nayar, a former vice chairman and chief executive of the information-technology giant HCL Technologies, and his wife, Anupama, are behind this effort. Their New Delhi-based Sampark Foundation is rolling out kits with these child-friendly teaching aids to 50,000 government schools and 3 million students across Uttarakhand and another poor state southeast of there, Chhattisgarh. (A smaller-scale programme is also afoot in Jammu & Kashmir.) The kits cover 23 basic math concepts.

Sampark is also training 100,000 teachers in government schools to use the aids. And it plans to add 100,000 schools and 7 million children in the next few years. The foundation boasts $100 million in funding, supplied entirely by the Nayars and representing more than half their wealth. “The business of philanthropy is the business of change, and this is large-scale social change,” says Nayar, 54. “I want to be at the centre of innovation.”

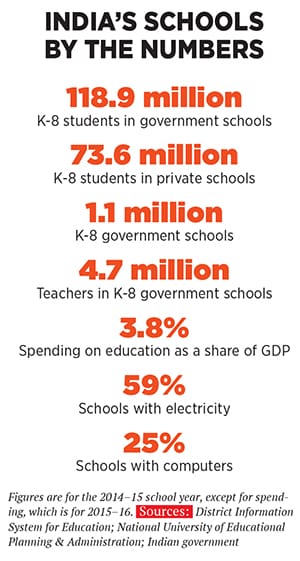

Many of India’s government schools in rural areas fail to teach their students very much. Some 76 percent of children in grade five can’t read simple sentences in English, and one out of five can’t recognise numbers above nine, according to the 2014 Annual Status of Education Report, compiled by Pratham, an Indian non-profit. Moreover, the government’s “no detention” policy allows students to move up from grade to grade, until eighth grade, regardless of whether they learnt anything in the previous grade.

“Currently, primary education doesn’t create the foundation necessary for further learning,” says Rukmini Banerji, Pratham’s CEO. “Half the children in grade five aren’t at even the grade-two level. They cannot make meaningful progress after grade five, when the textbooks get bigger and the curriculum gets heavier. More and more children lag behind.”

Nayar’s vision is to dramatically raise the level of math—and also English—skills of primary school students. He believes that this can be done by making the classroom more exciting, using toys, folklore, stories, games, audio lessons, songs and hands-on activities to increase the students’ attention spans. (In a typical classroom, the teacher uses only textbooks and the blackboard.)

For instance, for teaching English, Sampark launched an audio device with a voice mascot called Sampark Didi (“older sister” in Hindi). It needs to be charged only once in 15 days, important because of frequent power cuts in rural areas. When the device is switched on, a zesty female voice starts off with a hearty, “Good morning, children,” reminiscent of a Bollywood actress in a hit movie. She then belts out stories and rhymes that are primarily in Hindi but gently introduce new English words. In one story, a fish called Nimmy brings up new words such as “tortoise”, “crab” and “sea”. These lessons are also for the teachers, who often are not confident about speaking in English. (The bulk of the teaching in government schools in northern India is in Hindi.) At the end of the lesson, the kids are quizzed on the new words they’ve learnt.

Nayar chose the device because audio doesn’t engulf the senses and leaves more room for imagination. It’s also less intimidating, inexpensive and easier to handle in schools with little or no infrastructure. He says he was inspired by how he grew up listening to dialogue from movies on tape—popular Hindi movies such as Sholay and English movies such as Mackenna’s Gold.

The emphasis in Sampark’s project is on what Nayar calls “frugal innovation,” so no fancy iPads or laptops. The cost is just $1 a year per child, totalling $15 million for the duration of the project. “If it’s not frugal, it’ll not scale,” he says. “We can only be the incubator for the idea. The scale has to come from the state.”

The aim is to ensure that within one year of implementation, at least 80 percent of the children can speak and write 500 new words in English and form 100 sentences. They should also be able to do basic addition, subtraction, multiplication and division.

There’s nothing revolutionary about the materials, but they’re easy to use and structured around the curriculum, so the students steadily build up a knowledge of the concepts. Take 10-year-old Sawan Kumar, one of Mathyal’s students at the Model Government Public School in Mehragaon. He uses a wad of plastic play money in his classroom to understand addition and the concept of money. He can touch, feel and play with the money, so he picks up the idea easily.

Sampark has around 100 employees based in the two states—many are graduates of the premier Tata Institute of Social Sciences—and they regularly visit classrooms to monitor the children’s progress and make sure the kits are being used effectively. Sampark, which means “connection” in Hindi, has also set up a helpline at the states’ education departments for teachers to call with questions or requests for guidance. If a high number of calls originates from a certain school district, the foundation provides refresher training. The project started off as a pilot programme for 500 schools in 2013; it was scaled up to 5,000 schools in 2014, and it now reaches 50,000 schools.

Key to its success is the support of the chief ministers of the two states, which together will spend millions on education this year. Sampark makes a presentation to the ministers every quarter, and they each do a quarterly review of the project. The progress of the 3 million children is tracked through an Android application. A five-year agreement with the states focuses on an ambitious goal: Getting these two school systems—among the country’s worst laggards—into the top five in terms of test scores.

Nayar learnt his lesson in 2011 when Sampark rolled out a similar programme for 5,000 schools in Punjab. “We spent a lot of money and got nothing out of it,” he says. “Learning outcomes didn’t improve. The state wasn’t behind the programme. So we added three key components: The audio device, people on the ground and a tightly knit partnership at the chief minister’s level to monitor and guide the programme.” Now, he laughs, “I have two chief ministers who are after my life, and both are angry that we are not rolling out the English programme fast enough.”

Nayar isn’t alone in his quest to tackle the problem of primary education. Pratham, with its motto of “every child in school and learning well,” focuses on reading comprehension in the child’s own language and problem-solving in math. The Azim Premji Foundation, supported by billionaire Azim Premji, works in some of the poorest districts in seven states and is involved in everything from textbook and curriculum development to improvements in student assessment.

The Agastya Foundation reaches rural kids via motorbikes equipped with laboratories in a box that cover various science concepts. In another effort, Infosys co-founder Nandan Nilekani and his wife, Rohini, recently started EkStep, a digital technology platform that uses games, apps and other tools to increase learning. “In spite of so many efforts, we’ve still not achieved universal foundational literacy and numeracy,” rues Rohini, who has co-founded several education initiatives over the past 15 years. “It’s frustrating and perplexing. We have to use all the technological tools we can to ensure that we can give students the extra help they need.”

The other problem is making sure the educational progress is maintained. “Learning outcomes typically spike during an intervention when the extra attention is there,” says Rohini. “The kids do well when the programme is on. But after that the outcomes drop off. There has to be consistent follow-up. The children need a lot of time, attention, care, energy and resources.”

A bigger challenge is that children don’t come to school regularly. Nationwide, more than 96 percent of children are enrolled in school, but many don’t attend on any given day even though the government provides free lunches, books and uniforms (for girls). The reasons are many—they live far away, they’re needed at home to do chores and watch younger siblings, and parental involvement is low.

Take Geeta Bhatt’s public school in Bhimtal district in Uttarakhand. On a recent Monday, only 12 of the 19 students in the school have turned up. “I would say about 7 or 8 of them are truly learning because they come regularly,” she says. The children lose their notebooks and uniforms. There’s little reinforcement at home, where the parents are often labourers, maids, cooks and drivers in the area. “The frustrating part is that you teach them a concept one day and the next day they don’t show up, so you have to start all over again.” Adds Nayar, who visits the schools at least once a month: “You go into a class. One guy doesn’t know addition; another doesn’t know division and another hasn’t attended school in ten days.”

Nayar grew up in Uttarakhand, but he went to the private Campus School and then earned an engineering degree from the University of Pantnagar. After an MBA from XLRI (Xavier School of Management) he joined HCL Ltd in 1985. He quit in 1992 to co-found Comnet, which specialised in managing remote infrastructure. Then in 1998, it merged with HCL Tech, and his stake in Comnet was converted to shares in HCL Tech.

By 2005, Nayar was all set to give up his corporate career and jump into social development. He started Sampark that year. But Shiv Nadar—the IT billionaire who co-founded HCL Tech (see box, page 41)—asked him to run the company. In the next eight years, Nayar boosted revenue sixfold, taking it up to $4.7 billion a year. “In 2005, I wasn’t rich and famous. I was okay and not famous,” he says.

The transformation at HCL and his 2010 book, Employees First, Customers Second: Turning Conventional Management Upside Down, which sold 100,000 copies, catapulted him to corporate stardom. “I left the corporate world after demonstrating my intellectual powers, after demonstrating that I could build a $1 billion startup and after demonstrating that I could transform a legacy company,” he says. “But after you’re intellectually satisfied it looks like a meaningless chase. The purpose of making higher and higher profits wasn’t alluring to me. I got tired of the quarterly earnings reports and the corporate environment. Where’s the purpose of your existence?”

In 2013, he quit HCL and defined his purpose as bringing smiles to a million children. The vision now is for 10 million. He devotes 80 percent of his time to philanthropy while also doing corporate consulting work; he puts that income into the foundation. (He’s also an avid Himalayan trekker who treks up to 14,500 feet. His goal? 19,000 feet.) “My wife and I have always wanted to do [philanthropy],” says Nayar. “We were never lured by the razzamatazz of corporate life.”

Anupama—she and Vineet were high school sweethearts—has a background in special education and brings insights into pedagogy and attention spans Vineet says his philanthropic ethos stems from his mother, Janak, a 12th-grade English teacher who raised three boys—he was the middle one—on her own after her husband’s early death. He says his mother always put aside money for charity. “I don’t need Warren Buffett and Bill Gates to teach giving to India,” he says heatedly. “We Indians have been giving for years even when we don’t have. To give when you don’t have is bigger than to give when you have. Giving is in our blood. Stop preaching to India. Start learning from India.”

So it’s unsurprising he’s not a fan of Giving Pledge, a campaign launched by Buffett and Gates in 2010 to encourage rich people to donate at least half their wealth. “The giving pledge is input-focussed. Just by giving away 50 percent you’re not solving problems,” he thunders. “I want 50 percent of your mind. Philanthropy has to be very deep and very innovative. It must create a larger impact, and that’s not measured in millions of dollars.”

Unlike most foundations, Sampark has an expiration date. It will shut down by 2025, he declares. He’ll also spend every last rupee in the endowment by then. “In HCL, I was building a company to last; here I am building a company to die,” he says. “Its work should stay. It should not stay. This is a different experiment. It’s like this: If you knew you had only three months to live, you’ll live your life differently.”

Sampark’s immediate goal is to expand the math and English programmes to three more states. After that, Nayar will make everything he’s learnt publicly available to whoever wants to introduce the project in a new location, but under Sampark’s guidelines. Then the plan is for science programmes for middle school children. By 2020, Nayar wants to take his model to schools in Africa. “We are pushing ourselves intellectually, and the purpose is the smiles on the faces of the children,” he says. “This is a recipe for bliss.”

THE BEST AND THE BRIGHTEST

Shiv Nadar has committed $1 billion to philanthropy

Vineet Nayar’s aim is to get millions of children to master the basics of math and English, while his friend, fellow philanthropist and former boss, Shiv Nadar, takes another approach to tackling India’s education crisis. Nadar, who pledged $1 billion to his foundation in 2013, provides a completely immersive experience to a select few middle and high school students.

The Shiv Nadar Foundation started a leadership academy in 2009 called VidyaGyan, a boarding school at which poor yet brilliant students from rural Uttar Pradesh are given access to a world-class education complete with exposure to theatre, the arts and sports. The first batch graduated this year, and of the 187 students, 139 averaged above 80 percent in their 12th-grade exams. Of these, 53 scored higher than 90 percent. The students—whose parents earn less than $1,500 a year—were selected seven years ago from 250,000 children in primary school. Four are now headed to the Indian Institute of Technology and four were admitted by the London College of Fashion. Many others will be pursuing university studies in courses ranging from science and engineering to hotel administration. Today VidyaGyan has 1,900 students at two campuses. The students typically do not speak English when they enter, but among the first graduates, 71 scored more than 90 percent in English. Nadar’s vision is for his school to mould leaders from rural India—maybe even a prime minister.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)