The rural route to recovery

The agri-focussed rural economy picked up as migrants returned home, but it will be a while before the benefits of the recent agri reforms reach all

A bountiful monsoon has boosted reservoir levels and crop sowing activity

A bountiful monsoon has boosted reservoir levels and crop sowing activityImage: Amit Dave / Reuters

Saab, sara anaaj khatam ho gaya hai (Sir, we don’t have any grain left in stock),” repeats JP Tiwari, a farmer from Tarabganj in UP’s Gonda district, for the fifth time that day. Tiwari gets regular calls from clients inquiring about his organic produce. The 60-year-old has been farming on his 8-acre plot for 20 years but it is only recently that he has moved to organic farming. “The demand for organic farming has shot up due to the pandemic. People now understand the importance of nutritious produce,” he says, adding that all the crop he has harvested has been sold. And he doesn’t have enough supplies to meet the lingering demand.

Unlike most other industries that have taken big hits, the coronavirus outbreak hasn’t broken business for the likes of Tiwari, who earns close to ₹6-8 lakh a year from farming. In fact, the reverse migration of labourers from big cities to their home towns helped Tiwari overcome workforce shortage. “Personally, I know 15 people who have refused to go back to cities. They want to stay here and are looking for land to start farming,” he says. Currently, he either goes to the Lucknow organic mandi or sells directly to customers who travel to his farm to purchase his produce. Through the PM Kisan Samman Nidhi Scheme, he gets about ₹6,000 every month directly in his bank account that he uses to purchase raw materials. “Given the increase in demand for medicinal plants, we have recently started harvesting moringa and shatavari,” he adds.

Like Tiwari, the sentiment in the agricultural market is positive for a number of reasons. The reverse migration prompted the government to announce an increase in its budget for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) by ₹40,000 crore, over and above the existing allocation of ₹61,500 crore. “Moreover, the farm sector hit a high during the pandemic with FY20 rabi production rising by 4.5 percent and a sharp rise in public food procurement,” says Prithviraj Srinivas, chief economist, Axis Capital.

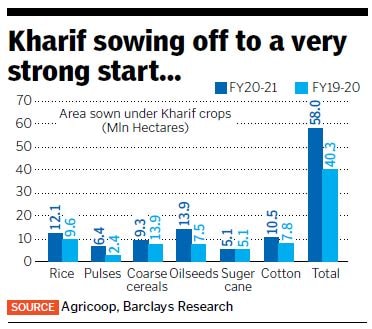

Besides, a bountiful monsoon has brought good news for farmers. According to a Barclays research report, the rains have boosted reservoir levels, with average storage running at 167 percent and 146 percent above levels seen last year and the 10-year average, respectively. Due to this, crop sowing activity has been significant. As of July 10, the area sown had already crossed 50 percent of overall arable area. Additionally, the announcement of the agri reforms along with the ₹1.5-lakh-crore package for agri infra that was announced in May—allowing barrier-free inter-state trade of farm produce, amendments in the Essential Commodities Act and farmers to engage with large retailers and exporters—are clear indications that a boost in agriculture, and consequently the rural ecosystem, might be key to India’s economic revival.

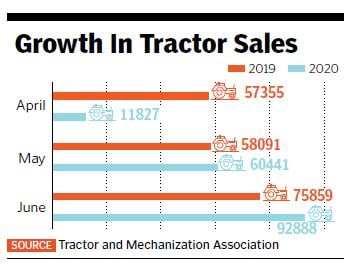

The increase in sales of tractors and FMCG products in the rural markets reiterate how agriculture is ready to turn the corner. In June, tractor sales (excluding exports) increased to 92,888 units, up from 75,859 sold last June (according to data from the Tractor and Mechanization Association), while domestic sales for Mahindra & Mahindra farm equipment in June saw a surge of 12 percent to 35,844 units, as compared to 31,879 units in June 2019, with good growth being seen in Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. “These underlying factors along with better cash flows in rural markets have helped boost tractor demand during June. It is expected this demand will continue to remain buoyant in the coming months,” says Hemant Sikka, president, farm equipment sector, Mahindra & Mahindra, adding that good reservoir levels and prospects of a good monsoon bode well for a good output of the kharif crop as well.

According to Sikka, the timely relaxation of the lockdown has enabled speedy recovery of the agriculture sector, which means production is now up to pre-Covid levels. “The recovery in tractor sales in May 2020 suggests rural consumer confidence was relatively insulated during the lockdown,” says Aditi Nayar, principal economist, ICRA.

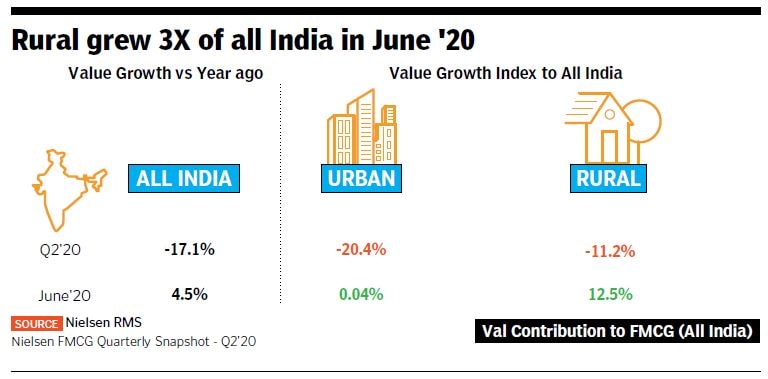

The FMCG sector has also seen an indirect benefit of the agri boost in the rural economy. “The reverse migration suggests a shift in where consumption will take place at the bottom of the pyramid,” adds Nayar. According to data analytics firm Nielsen, the FMCG sector has touched pre-Covid-19 level sales in June primarily due to a rebound in rural consumption and sales from traditional channels. Rural markets, which account for 36 percent of FMCG sales in India, grew three times the all-India sales (see graphic). “Given the reverse migration of labour, government stimulus, a good rabi season and no adverse impact on agricultural output during the ongoing Covid-19 crisis, rural grew 20 percent in the first quarter of FY21, compared to the FY20 average,” says a Marico spokesperson.

Tractor and farm equipment sales have seen a surge and good growth is being seen in Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh

Tractor and farm equipment sales have seen a surge and good growth is being seen in Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Telangana and Andhra PradeshImage: Bharat Bhushan / Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Given that rural consumers have shown a clear pattern of preference towards categories like personal hygiene and natural health care, many FMCG companies are making forays into this space. “Currently, the growth momentum is encouraging and this positive traction is expected to sustain over the next one or two years. In comparison to urban, rural demand has been more stable. The growth in the rural market is, however, largely driven by smaller packs as has been the case always with rural consumers, who are more cautious in their spends,” says Harsha V Agarwal, director, Emami. For instance, Emami launched BoroPlus sanitisers and also introduced Kesh King Shampoo in sachet format to give it a rural push.

During the lockdown, CavinKare launched a range of sanitisers—also sold in a sachet size for rural markets—as well as of disinfectants and a fruit and vegetable wash. Says Venkatesh Vijayaraghavan, CEO & director, personal care & alliances, CavinKare, “It appears that rural seems to have more external stimuli of cash or growth and we do hope it sustains though the subsequent quarters.” ICRA continues to expect agricultural GVA to rise by 3.5-4 percent in FY21, supporting rural sentiment, equivalent to the 4 percent that the country’s agriculture and allied sectors grew in FY20.

Reverse migration has contributed to the growth of the FMCG sector in rural areas, with the growth largely driven by smaller packs

Reverse migration has contributed to the growth of the FMCG sector in rural areas, with the growth largely driven by smaller packsImage: Tim Graham / Getty Images

While the sales of essential products are back to pre-Covid levels, those of non-essential products are yet to recover fully. “While factories are coming back to normal albeit with lower manpower, logistics continue to be a challenge with last-mile connectivity being affected by micro lockdowns across the country,” says Vijayaraghavan.

Besides, the positive sentiment is mostly woven around products that boost health and immunity, buzzwords birthed by the Covid-19 crisis. Consider that Balasaheb Temgire, a ‘non-organic’ farmer from Ranjani in Pune’s Ambegaon, has been waiting for two years for things to look up. First, the floods in Maharashtra last year destroyed 75 percent of his potato crop. This year, the pandemic has sent his onion prices plummeting. “All my onion stock is just rotting away,” says Temgire. “Sometimes I go to the local mandi to sell it, but the prices are low.” Usually, he makes good money through exports to Gulf countries, but the demand has fallen this year. With exports and transportation stuttering due to the lockdown, stocks have either been rotting in godowns or are being sold off dirt cheap.

“In some cases, the exploitation is more in rural areas as traders are cashing in on the increased demand from cities without passing on the benefits to the farmers,” says Puneet Sethi, co-founder, Farmpal, a farm-to-market company. Temgire has been supplying to Farmpal for close to three years now. “Farmpal bought all my cucumber stock for ₹70,000, which I will be saving,” he says. But he claims he has no money to spare to invest in land or farm equipment.

Sethi adds, “Amid the current situation, farmer willingness to explore alternate supply models other than mandis increased significantly since their traditional selling mechanisms had been impacted.”

Demand is volatile, says Temgire. “Right before a phase of the local lockdown, there is a sudden surge and then no demand for a few weeks. Once the lockdown opens up, demand increases by 3-4x again,” he explains, adding that prices are also fluctuating between two extremes. Temgire, more than anyone else, is in dire need of good agri infrastructure to store his produce, especially during such times. “We hope the government considers setting a Minimum Support Price (MSP) for fruits and vegetables as well. It will help us recover the basic costs of cultivation, especially during a price crash,” he says.

Another agri entrepreneur, Parth Tripathi, CEO & director of BeeHively Group & Krishna Agro, feels the overall situation in agriculture has not been up to the mark since the past few years. Through Krishna Agro—a farmer producer company—Tripathi works with close to 50,000 farmers across Uttar Pradesh, helping them connect with mainstream players, from large FMCG companies to agritech. They have also worked on several large projects with the state government. “When the pandemic was announced, it was peak harvesting season for wheat. That caused a delay in harvesting even though permissions were later given,” he says.

Besides, as most migrants returned to their hometowns later since they were stuck in cities through March and April, it led to a labour crisis that hurt even the large players. “Some of these companies told farmers they won’t be able to buy the quantities they had earlier committed to,” says Tripathi. Due to the lack of storage facilities, the remaining stock had to be sold at local mandis at significantly lower prices.

Generalising that all farmers have benefitted due to the pandemic would be incorrect, according to Vilas Shinde, chairman, Sahyadri Farms. “Only some farmers, for instance, those who were growing citrus fruits such as oranges or sweet lime have benefitted due to a rise in demand. Others such as cotton or sugar farmers have suffered heavy losses,” he says.

While the government has put in place the new agri reforms, the increasing cost of cultivation—farm equipment, labour, fuel, logistics etc—has offset many of those benefits. “While the cost for each of these has increased, it is the hike in diesel prices that has caused the most damage,” says Shinde. However, coronavirus has helped encourage farmers to shift to organic farming. And with the increase in demand for immunity boosters including honey, a lot of Tripathi’s farmers have started farming medicinal plants and beekeeping. Additionally, Shinde of Sahyadri Farms believes an ecosystem is necessary to help small and marginal farmers. “It is not enough to have only reforms or finance-related policy.”

With the ₹1.5-lakh-crore package for agri infrastructure, Hemendra Mathur, venture partner at Bharat Innovation Fund, an early-stage venture fund that invests in agri innovation startups (among other sectors), believes we need a ‘Mandi plus’ model. “At a smaller scale, we are not only aggregating, but also doing quality grading and assessment. Based on the grade, prices can be set. This will also encourage farmers to produce better quality,” says Mathur. The shorter the supply chain, with only two to three intermediaries between farmer and consumer, the more the value creation, he adds.

Besides, there should be micro warehouses at the farm level and rural entrepreneurship should be encouraged by setting up primary processing units. “So far, the focus has only been on pre-harvest financing for farmers. Banks and NBFCs should also focus on post-harvest financing,” he says.

While agriculture is likely to drive rural growth, to what extent are the government’s schemes and policies impacting farmers at the ground level? Temgire says: “We hear and read about these schemes and packages in the newspaper. But we don’t know when that money will reach us.”