The Whethermen

Indian scientists are trying out a new climate model to get monsoon forecasts right. If they can get it to work, expect it to rain when they say it will

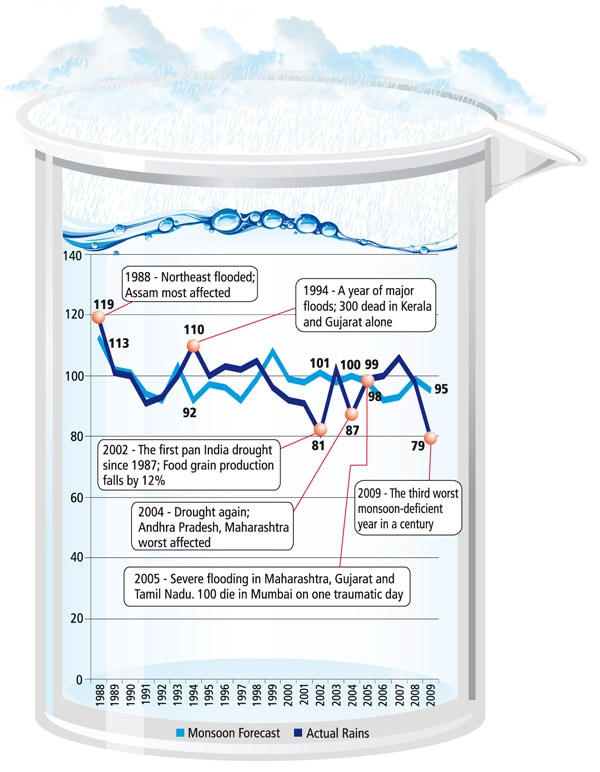

It was going along quite swimmingly till 2002 for the weathermen of India. The Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) forecast a normal monsoon for that year. As the season wore on, it became clear that the monsoon would be anything but normal. It was 19 percent below normal and India experienced its first drought after 1987. This resulted in a 12 percent decline in food production. Weathermen couldn’t explain why they had been unable to see it coming. “There was little understanding of what had happened. And different institutes had different explanations for the deficiency,” says M. Rajeevan, scientist at the National Atmospheric Research Laboratory.

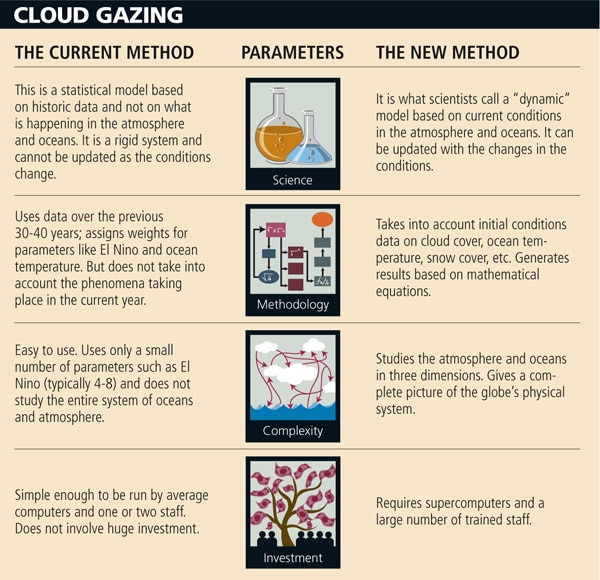

Given that 65 percent of Indian farmers depend on the monsoon for irrigation, a failure of this kind has serious economic and political consequences. The IMD went back and checked its crystal ball — the climate model, a mathematical formula that incorporates a large number of factors that cause the monsoon and predicts the total rainfall in a season. IMD’s model took into account 16 such factors. This model was tweaked. Things improved in 2003 when IMD’s forecast more or less matched the real thing. But in 2004, the forecast went wrong again. Another drought hit the country. Things have been up and down since then. After every year or two, the forecasts go awry. “When the monsoon fails, GDP falls by almost 2-3 percent. It has a huge cost on the agricultural sector. Even in 2009, agricultural production fell by about 7 percent from 234 million tonne in 2008 to 218 million,” says Dev Raj Sikka, an experienced meteorologist.

Say Hello to My New Friend

The government of India has had enough and wants the weatherman to get his mojo back. In India, there are more than 10 organisations that study climate. One of them, the Pune-based Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), has picked up the gauntlet. “Few institutes want to do it because it involves a lot of investment — in money, training of human resource and time,” says B.N. Goswami, Director, IITM. Goswami is 60 years old and stands maybe five foot four. He is light on his feet and scurries about the Pune campus to show off his Brahmastra. In a large building located 80 metre from his office sits the big IBM pSeries 575 supercomputer. It can do 18.8 billion floating point operations in a second. Goswami is now looking to hire more Ph.D.s who understand various aspects of climate and also programming talent to use the supercomputer to look into the future.

Infographic: Sachin Dagwale

But all the manpower and the hardware will be of little use if Goswami can’t improve the underlying logic of weather prediction. He is betting on a new method to predict the monsoon accurately. Scientists call it a ‘physical’ or ‘dynamic’ climate model. Since it is supposed to be more exact and rigorous, the ministry of Earth Sciences has agreed to foot the bill for the beast in IITM’s backyard. If Goswami can prove it works, this is the model that IMD will use for its forecasts.