US visa struggles push Indians beyond American dream

Indians in the US have struggled with H-1B renewals and decade-long Green Card queues for a few years now, living in constant uncertainty. What next for them, and how can India attract this talent back?

Praneetha Korlepara joined her husband Vinay in the US in 2008. They moved back with their daughter Tanvi in August 2019

Praneetha Korlepara joined her husband Vinay in the US in 2008. They moved back with their daughter Tanvi in August 2019

Praneetha Korlepara moved to the US in 2008 once she got married, to join her husband, who had lived there since 2003. With a BTech degree and no master’s, she had scant job options while the country was struggling through recession. An employer would have to sponsor her visa. However, her husband’s company had promised a Green Card filing by 2009. Anticipating this, Korlepara enrolled into a master’s programme, dipping into savings, and sacrificing on travel and socialising in their early days of marriage.

“By the time they filed the application, it was 2011. I had graduated,” she recalls. This meant that she was now on the post-study Optional Practical Training (OPT )visa, which runs on a time limit. Two years later, she was pregnant with their daughter, and her husband, who works in the medical devices industry, decided to switch companies for better growth—he joined an early-stage startup. “A month after my daughter was born, he was given a two-month notice and laid off,” she says. “We were truly stuck; his H-1B visa would run out soon if he didn’t find another job.”

Luckily, he did just before their deadline ran out—but in a remote part of Indiana (many core health care jobs are outside of cities), where even a ride to the mall was an hour and a half away. “We accepted a pay cut and moved there, in the peak of winter with a month-old baby, because we had no choice,” she recalls. “I was going through post-partum depression and matters didn’t help. I was so stressed, I couldn’t feed the baby, and she would keep falling ill.”

Korlepara, herself on an H-1B visa by now, had to return to work at a consultancy firm when her daughter was three months old, and was called in for in-person training to Ohio. For a month, she had to spend the week there while her husband would manage work and the baby by himself, and travel back home over the weekends. “Even then, I would spend most of the time cooking, so they would have food to last the week,” she says.

“We couldn’t choose where to live because we were so visa dependent. We had to go where the employers were, and where they would be willing to sponsor our visas. I couldn’t give up my job either,” she says. “My husband had patents pending, so leaving the country was never a thought back then.”

The constant uncertainty caused their marriage to suffer too. They found themselves stressed all the time. Relations with their families had soured over time, so they had no shoulder to cry on—“I always considered my career that shoulder, that crutch,” says Korlepara.

In 2016, she got involved with policy groups that deal with immigration advocacy. “This gave me an understanding of the politics behind some of these decisions. With this new knowledge, my husband and I started to question whether this stress-filled life was really worth it,” she says. “Our daughter was five years old by now, but still young enough to be able to adapt to life in India. The opportunities in India had opened up, unlike when he moved to the US in the early 2000s.”

Her husband interviewed for jobs in Germany, Singapore, Gurugram and Bengaluru—until he landed an appropriate profile in Pune. “The day we made the decision to go back to our country, I felt like I had been released from jail,” Korlepara says. “We came back in August 2019 and feel so good being back home. And if you ask my daughter—who faced some level of racism being among the only Indians in a remote town—she will immediately say she prefers India!”

*****

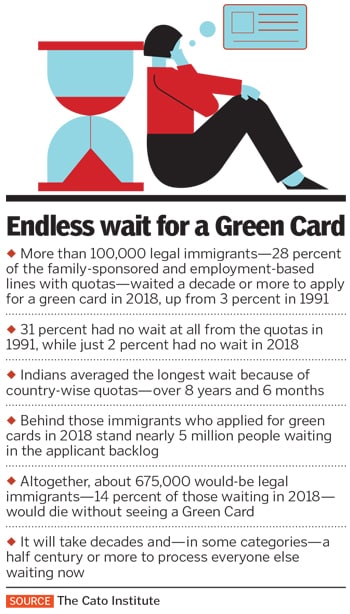

The Korleparas are among thousands of families who live in fear, chained to jobs they don’t particularly want, or stuck in Green Card queues that last decades.

In 2020 alone, the US received nearly 275,000 unique registration requests for the 85,000 H-1B visas available for foreign technology professionals; of these, more than 67 percent are from India. H-1B is the most popular category with Indians in the US.

In 2019, the US issued 188,123 H-1B visas for both new applicants and renewals. Of these, 131,549 were to Indians; and 28,483 to Chinese.

According to the Department of State, while 13,678 H-1B visas were issued in May 2019, only 143 were issued in May 2020.

In the middle of June, US President Donald Trump announced a suspension on the entry of foreign workers (and therefore, issuance of new immigrant visas) until the end of the year. This move is largely seen as an election tactic to appease Trump’s voter base and unlikely to extend beyond the moratorium; even so, it is a telling sign that the climate around immigration has changed significantly over the past few years.

On July 6, the US also announced that foreign students whose classes had moved online in the fall semester because of the coronavirus would be forced to leave. The State Department “will not issue visas to students enrolled in schools and/or programmes that are fully online for the fall semester nor will US Customs and Border Protection permit these students to enter the United States.” Most US colleges and universities are yet to announce their class plans for Fall. On July 14, Trump revoked this order, after a lawsuit from universities including Harvard and MIT.

“My business has been focussed on EB-5 [an employment-based visa route by which immigrants must invest $900,000 into the US and its businesses], which was a sleepy programme, but became red hot after the 2008 recession as businesses looked for capital,” says Suresh Rajan, executive chairman and founder of LCR Capital Partners, a private investment and advisory services firm. “It’s not a permanent programme. In 2012, it got renewal in the US Congress by a unanimous 98-0 vote. Three years later in 2015, it almost didn’t get a renewal. The environment here around immigration had become so toxic in such a short period of time. It was shocking.”

When Trump campaigned for the 2016 elections, one of his main points of posturing was to create American jobs for Americans, limiting those for immigrants. “I will end forever the use of the H-1B as a cheap labour programme, and institute an absolute requirement to hire American workers first for every visa and immigration programme. No exceptions,” he said in March 2016. For the upcoming November election, too, his agenda remains the same.

“What’s happening is absolutely political,” says Anil Advani, founder, Investus Law. Advani is also a member of the USISPF Startup Connect programme, which focuses on cross border startups across the US and India. “There’s a divide in the country, but also in the administration on what’s good for America.”

The Trump administration, he says, seems to think that Silicon Valley is not the driver for the American economy, whereas the rest of the world does. “There’s a disconnect on where the economic impetus should be. The government thinks agriculture, old industries are the way to return to the old American superiority, but the world has shifted. The reason the US is a superpower and has an advantage over other countries is because of the tech companies. There’s good evidence to show that immigrants play a large role in this.”

Experts say not much will be lost with this year’s visa restrictions; with Covid-19, hiring has plummeted, as have travel plans. The new restrictions won’t affect those who are already in the US, but fresh applications—most of whom won’t be able to travel until the end of the year in any case.

The fear, though, has set in.

Advani says it has become difficult for him to advise Indian founders to invest in the US when they think the US doesn’t want them. “But I tell them that if they have long-term plans beyond this year, I can’t imagine these current restrictions will continue. The president’s followers are about the optics and theatrics; even if he were re-elected, he would face economic pressure from tech companies, many of whom contribute to his campaign. Either ways, the administration would roll it back,” he says.

This is not a new problem, but it has exacerbated over time.

“People have been stuck with companies and been in limbo for a while as the Green Card situation has been bad,” says Anand Akela, a seasoned Silicon Valley marketing professional and startup advisor, and a member of the board of TiE’s Silicon Valley chapter. “In fact, even if they travel to India, they worry about whether they will be able to come back. They haven’t seen their families back home for years, thinking they will plan their trips after the Green Card is settled, but that’s a moving target. Their parents are getting older, but they cannot visit. They want to keep their dream alive here too.”

When Jyoti Bansal, founder of Silicon Valley tech firm AppDynamics, moved to the US as an engineer on an H-1B in 2000, he had to wait seven years for his Green Card to be processed to be able to start his own company.

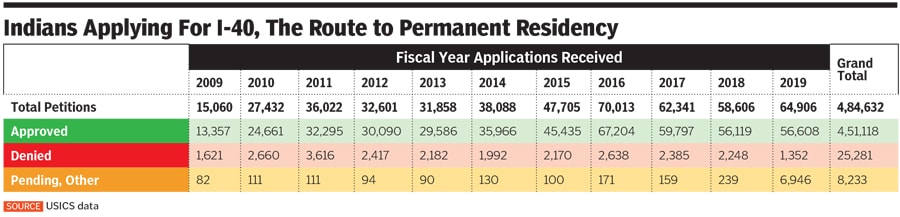

“I could’ve started my company three years sooner than I did because of these issues,” he says. “These days, instead of seven years, it could take decades. It could be a loss to the US startup ecosystem, but a gain to India’s, as people may move back to start their companies up.” Data shows that the number of pending Green Card applications went up from 239 in 2018 to almost 7,000 in 2019, a jump of almost 35x (see box).

Reverse brain drain?

A lot has changed in India since the early 2000s, especially for entrepreneurs, but it may not be the top choice for those who have lived overseas for a long time.

“My guidance for people usually depends on what their goals are, where they are in their family situation,” says Akela. “It’s more difficult to move back when you have older children, who will find it harder to adapt to life in India, for instance.”

In general, he adds, the technology and software areas could see great potential in India. “The information side of health care will also do well—archival, retrieval and so on can be done remotely easily,” Akela says. “Animation and post-production in entertainment too. A lot of the things that are dependent on information systems will benefit from a return to India.”

Ashwini Asokan, founder and CEO of AI company Mad Street Den, moved back to India from California in 2014 with her husband Anand to ride the growth wave back home

Ashwini Asokan, founder and CEO of AI company Mad Street Den, moved back to India from California in 2014 with her husband Anand to ride the growth wave back home

Ashwini Asokan, founder and CEO of Chennai-based artificial intelligence (AI) company Mad Street Den and its product, Vue.ai, moved back to India from California in 2014, along with her husband, Anand—not because of visa struggles, but to ride the growth wave back home. When they moved back, their older daughter was three; a year later, they had their second child, and started up the company together.

“We had not lived here as adults. To come back with children, it took us a couple of years to adjust to the life,” says Asokan, who used to run mobile innovation at Intel back in Santa Clara. “We had a different view of what AI should be than what we were seeing in the Valley at that time. We were not interested in building a developer community. We had strong opinions of how we wanted to build the company. But more importantly, we wanted to do it in Chennai, in our hometown.”

The couple initially moved to Benglauru, but within six months, packed up for Chennai. “The deep tech and SaaS (software as a service) talent in Chennai is incredible. It was the perfect storm of B2B and deep tech coming together,” she says. “It’s a great college town. Anand and I were passionate about coming back, dipping into that pool and growing with that pool.”

There have, of course, been challenges along the way. One of the things India’s startup ecosystem—bustling with new, young companies—misses, says Asokan, is strong leadership. “When we started the company, it was really hard to find people qualified in product. India has been largely focussed on services. But all of that has changed in the past five years. You have some fantastic companies building fantastic technology here.”

“Historically, we don’t have many startups that have become truly big, the equivalents of the Googles or Facebooks of the world,” she adds. “It’s taken time for those companies to grow to where they are. We do need people with solid training, and working in the US, in Silicon Valley, gives you really valuable experience in growing companies.”

It’s a classic feed cycle—pipeline problem, growth opportunity problem, a talent problem—and once you start feeding that cycle, it’s an ascent to the top. “It all adds up, and starts to multiply, and begins to become exponential at some point. It’s taken us a good 10 years to get here, but we’re beginning to see a rise in the rate of growth, and the finance and expertise to support founders.”

The startup ecosystem in India also needs intervention in terms of legal and regulatory hurdles, experts say. “The system doesn’t protect founders, legally or tax-wise,” says Advani of Investus Law. “Angel tax came out of nowhere, and the fine print on it is still unclear. The biggest story coming out of India has been Flipkart, which is great for the founders, but the investors are now dealing with potential criminal action because of regulations. You can say what you want about Startup India, but these are realities investors and entrepreneurs are dealing with on the ground.”

The working culture back home could take some getting used to too, as 27-year-old Abhinav Gupta, who moved back from the US in 2019, is finding out. Gupta, who works at an oil and gas company headquartered in Canada, lost out on the H-1B lottery through all his attempts. He couldn’t transfer to Canada as he had not yet worked the mandatory one year at his current firm; he transitioned to their Mumbai office instead.

“I hadn’t worked in India before, and it was a bit of a shock on some days,” he says. “For instance, if you set a meeting for 10 am in the US, every person is in the room by then and the meeting starts even if someone is missing. Here, you wait 15, 20 minutes, then have to call people who are missing as though they need special invitation. Moreover, there is little focus on continuous growth; systems are rigid here, and it takes a lot of effort to change the way things work.”

While Gupta is glad to be by his parents in Nagpur during the lockdown, he is looking for avenues to return, either to the US or to Canada. “Work experience is definitely better there. Canada is a great option, but they don’t pay as much as the US does,” he says.

Another issue is that of funding—while the venture capital (VC) ecosystem in India is maturing, Silicon Valley still holds much of the world’s investment appetite. “Some startups can solve this problem with having one foot in India, one in the Valley—a lot of them already do,” says Sudhir Kadam, Silicon Valley entrepreneur, investor, professor and startup advisor. “I was once part of a startup that had 500 employees—and only 12 were based here in Silicon Valley. The support, implementation, services, can all happen from India. What you need here is sales and marketing people, who understand the local market and culture.”

The Covid-19 pandemic will help accelerate this opportunity. “We’ve been on digital steroids of WFH (work from home) for the past few months. Why do resources need to be on shore? They can leverage tools such as Slack and Zoom, stitch together a dispersed workforce. The visa no longer has to be an impediment,” Kadam adds. “In a growing company with global aspirations, founders will have to travel; they don’t need to be restricted to one country or one kind of visa.”

Countries calling

With the US making life difficult for immigrants, other countries are keen to capitalise on the talent it may lose out on.

“Canada’s a great place, and they’re being smart about projecting a friendly image for engineers, technologists, startups,” says AppDynamics’ Bansal. “A lot of European countries have been opening up immigration policies.”

“I’ve already seen a lot of Canadian ads for VCs, employers, consulting companies trying to lure people,” agrees Akela, citing Australia and Singapore as other alternatives. LCR Capital’s Rajan says it would be a good idea to look at countries that back the US up for services currently—in places like the UK, Germany, Ireland and Canada, Indians could find opportunities with the same clients as they do in the US.

Advani of Investus Law says he has been working on a long-term project to set up a process by which founders could set up a US company that can still take the same investments structure and IP, but have the founders fly in and set up in Canada.

“The US company could set up an entity in Canada. Vancouver is two hours away from Silicon Valley, and they can fly in and out on business visas. We have not needed to drive these options yet, but we could if this climate continues. However, the source of capital will still remain, at least for our generation, in Silicon Valley,” he says.

A lot of founders will look at such creative ways of getting access to the US market and Silicon Valley mentors and investment, while setting up in other countries for daily life and business, experts predict.

“No country has the monopoly on innovation. I’m always looking at Israeli startups—what a force of life they are,” Asokan says. “The way that community pulls each other up, that’s something India really needs to find out how to do. It’s completely backed by the government and their partnerships with other countries. The kinds of relationships that are present across those countries are amazing, they make it so easy for startups to succeed. I’d love to see that in India.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)