Will N Srinivasan Save Indian Cricket?

The richest cricket body in the world can't stop the declining interest in the sport. Can BCCI President N Srinivasan revive it?

On the face of it, this may sound contrived. But fact is, to understand cricket and the skulduggery that now beleaguers the sport all of us Indians love so hopelessly, you ought to understand a bit of how the cement business operates in this country. This, for one simple reason: N Srinivasan—president of the Board of Cricket Control in India (BCCI), head of the Tamil Nadu Cricket Association, and owner of Chennai Super Kings (CSK) at the Indian Premier League (IPL)—is also managing director of India Cements.

And it is at India Cements, a company his father founded in 1946, that Srinivasan earned his spurs. He once told a colleague of ours a couple of years ago: “I don’t go looking for fights. Fights come looking for me.” And the man knows to fight hard!

Now cement is what people describe as “smokestack” businesses—a polite way of saying old-world businesses where no corners are given, folks keep their head down, talk little and simply fight tooth and nail for every little penny. It’s a world Srinivasan is intimately familiar with.

For instance, there was this time when Ambuja Cements was a big name in the business.

A rapidly growing company in Western India, the then chairman Narotam Sekhsaria badly wanted a toehold in South India. The only thing holding him back was the cost of transporting cement down there from his plants in the west.

A shrewd Sekhsaria figured he could offset these costs if he used the sea. But even as he was putting a plan into place, environmental lobbies sprung into action, petitioned the courts and argued that this would damage the coast. The courts ruled in favour of the green lobby and Sekhsaria had to shelve his plans. There is no way to corroborate this. But it was then alleged that it was Srinivasan who’d instigated the green lobby. When asked about this, he then said with his trade mark straight face, “I think they just lost interest in the south. I was lucky.”

Call it luck, call it whatever, India Cements soon turned into a profitable business under his hawk-like gaze. But there’s also something disconcerting about the gaze. Though he’s soft spoken, something tells you, you ought not to get on his wrong side. People we tried to connect with, didn’t want to speak ‘on the record’ about the BCCI. “The BCCI is like the Kremlin,” they told us. “Srinivasan is extremely conservative. He was always very efficient and methodical. But he doesn’t delegate much.” It’s the kind of work ethic that helped turn around the cement business.

He’s part of a world that rebuilt a Ganesh temple that had gone to ruin outside the Chepauk stadium in Chennai because he believes it watches over the Tamil Nadu Cricket Association. By all accounts, he fits all the text book clichés of the south Indian businessman.

Now, Lalit Modi is the antithesis of all that Srinivasan embodies. He likes the good life, glitz, and glamour, possesses an entrepreneurial zeal that can only be described as mercurial; but most importantly, has as many friends in high places as he has enemies. Put all of these traits together and what you have is the story of a man who created the Indian Premier League (IPL), which lies at the heart of this story.

To put the league together, he needed the blessings of the BCCI—which at least on paper, was created to popularise cricket in the country and is a not-for-profit entity. But in a series of moves that can only be described genius, he subverted the system, appointed himself commissioner of the league and catapulted himself into the limelight.

In doing that, he got monies into cricket that was unheard of. But also committed a series of gaffes and was soon ousted as IPL Commissioner. He now lives in London claiming threats to his life from the underworld. But that is another story altogether. The real story is that in creating the IPL, Modi set into motion a system that has now collided with the more sedate world Srinivasan lives in—so much so that things almost seem to have spiralled out of control and Indian cricket looks like it’s in a morass.

We tried to talk to Modi for his version of the events that have led to the current situation. He sent a detailed reply, but with a caveat—all of what we write had to be cleared by him. We declined because that goes against our editorial policy.

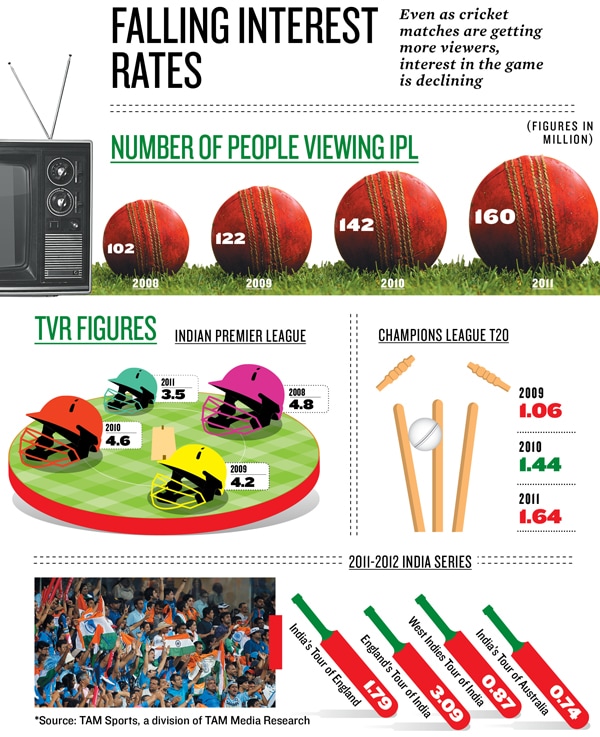

When Lalit Modi rolled the IPL out, it attracted millions of new viewers. But recently, the numbers of people watching the tournament (TVRs) are falling. Last year, there was a legitimate reason. People were tired after watching India win the World Cup and fatigue had set in. “The IPL followed the emotional high of an Indian World Cup win,” says Sundar Raman, IPL CEO.

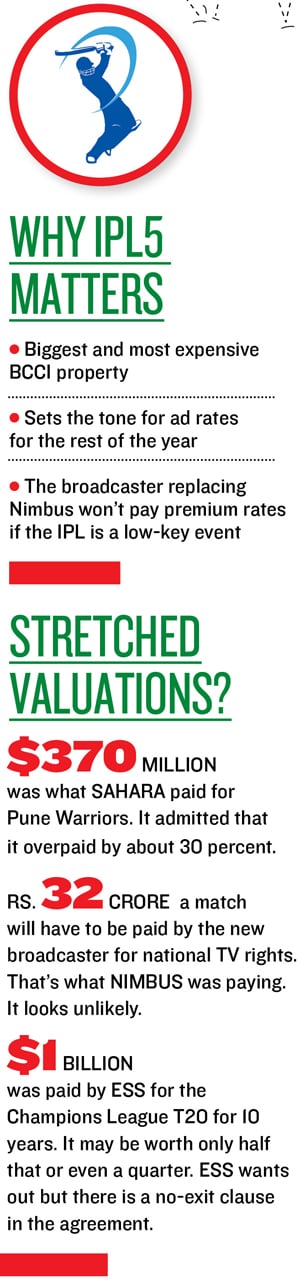

But fact is cricket hasn’t recovered since then. The IPL was followed by a horror tour of England. Matters got better when India thrashed England on the return leg; but West Indies’ tour of India didn’t get people excited. India’s tour of Australia put viewers off completely and cricket has been on a downward spiral. That is why IPL 5 is so important. The league gets in at least half of BCCI’s revenues. If it doesn’t get ratings to shoot upwards, the BCCI’s two other big properties, the Champions League T20 (CLT20) and international matches played in India will get into a downward spiral as well. The knock-on effect is not felt in the ad rates for the current series but the next one. So, now, advertisers are asking for a minimum guarantee viewership for the next big tournament: IPL.

Image: Adnan ABidi/ Reuters

A sports consultant who was involved with the creation of the IPL says, “The reasons are not difficult to find. The basic design of the league was tampered without a basic understanding of its components.” He points out that unlike the English Premier League (EPL) or the National Basketball Association (NBA) in the US, loyalties in the IPL were driven not by geographies, but by the star players. When players moved, loyalties did as well.

And when the duration of the tournament was increased in an attempt to milk more out of the tournament, it backfired. The league matches were instantly discarded by viewers as irrelevant.

Modi had gotten that bit right. Broadcasters, advertisers and brands were all lured by the magic. There is no other sport in India that can pull in people like cricket can. Not surprisingly, everyone wanted to be a part of the gravy train. Just that they’re discovering to their horror the gravy is all but over.

Nimbus, which had renewed its broadcast deal in 2009 with BCCI for $431 million for all international matches in India, couldn’t stick to its commitment of Rs 32 crore a match. Sahara admitted that they paid 30 percent too much for Pune Warriors. They’d gotten it at $370 million.

Even as the IPL was growing in stature, the BCCI floated the CLT20. The idea was to take the format global and teams from Australia and South Africa were roped in. Those who’d missed the train earlier with the IPL, now clambered on board. Nobody then knew how horribly wrong things could go.

Bharti Airtel pulled out as the official sponsor of the CLT20 after just one year. It thought the $13 million being paid each year for the sponsorship rights was too high. But ESPN-Star Sports (ESS) paid the highest price—$1 billion for rights to the CLT20 for 10 years.

To make money, they need to get TVRs (television ratings) of at least 4. That’s when advertisers pay premium rates. The highest they got was 1.64 in 2011. A sports analyst who doesn’t wish to be quoted says they paid at least double what the tournament was worth, if not two-thirds more.

To be fair to the BCCI, they did not ask ESS for that kind of money. ESS needed a marquee property to counter their rivals in India—Nimbus and Sony. When BCCI announced the CLT20, they paid for what they thought the tournament was worth.

“I think they should give it [CLT20] up,” says Mona Jain, CEO, VivaKi Exchange, the consolidated media buying arm of Starcom MediaVest Group, Zenith Optimedia, Solutions India and Digitas India. However, ESS has signed a no-exit clause for the tournament.

On the face of it, BCCI is sorted out for the next six years when it comes to money. Its deals with Sony and ESS last until 2018-19. But they have to make sure that broadcasters don’t feel left out of the riches. You can’t have a partnership where one party takes all the money and the other is left with crumbs.

The money that the BCCI stands to make year after year will hold it in good stead with the state associations, members of the BCCI who depend on it for running the game in their region. The associations trust the BCCI to take care of them, and as long as that trust is maintained the BCCI should have no problems.

The 27 state cricket associations are the ones who can decide who comes to power in the BCCI. It’s not easy for the BCCI to take them on. Most presidents usually have a hands-off attitude toward them. Around 70 percent of the money television rights brings to the BCCI is distributed evenly among the states. Then they receive any surplus monies from the IPL after its various stakeholders have been paid.

State cricket associations receive anywhere from Rs 10-15 crore a year from the BCCI. The money is given to them to improve cricket in their region. But that rarely happens. “State cricket associations have a huge role to play and if they start playing their roles properly they can take care of themselves,” says Aakash Chopra, former India opener.

Having a strong state structure would mean that the BCCI will have to haul up non-performing state associations and take them to task. Ostensibly, the BCCI audits the books every year before releasing funds. But that is largely an exercise in futility. “In some sense, this is a way to get their support and Srini[vasan] has not tried to change that,” says the former member of an association.

Forbes India (February 2011 issue) had written about the Rajasthan team that won the Ranji Trophy in 2011 (it also won in 2012), never having won it before. This year, the Rajasthan Cricket Association (RCA) got a new head in CP Joshi and he immediately went back to the days when factionalism was a norm. The RCA has refused to share cash incentives with professional players.

That has been the problem with the state associations and BCCI ever since the Board’s founding years. The Board cannot hold them accountable. Another member adds, “It’s just like politics. Ultimately, if you want to get anything passed in the BCCI, you need votes. Most of them [associations] will say yes because of the money. If they say no the implications can be severe and will change the power structure.”

It usually means that there’s a coup brewing. The most recent example was that of Jagmohan Dalmiya. He lost a bitterly contested election to Sharad Pawar in 2005 and that signalled his end. “Lalit Modi (though he was never president), Shashank Manohar and Srinivasan were paranoid about not repeating the mistakes that Dalmiya did,” says a former BCCI employee. Monies have been generously distributed to state associations and there hasn’t been a coup since. Pawar and Manohar completed three-year terms before retiring and Srinivasan appears to be following the same path. Last year, Dalmiya returned to the fold, and it looks like Srinivasan has patched up with him by not pursuing the cases that the BCCI had filed against Dalmiya in 2006.

This is not to say the BCCI hasn’t tried to get matters going. The introduction of Plate (junior) and Elite leagues in the Ranji Trophy has made the tournament much more competitive than it used to be. Rajasthan, a Plate team, has won the Trophy twice. Srinivasan says it has revitalised the Ranji Trophy itself.

The Board is also experimenting with a new structure for grooming talent. Since most states do not wisely spend the funds that are given to them, the Board is starting three academies that will serve as special zones for different regions.

Think of it as three National Cricket Academies being added. Srinivasan says domestic cricket and Tests occupy highest priority in the BCCI’s agenda. He claims the quality of wickets in domestic matches is going to improve and the number of A-team tours will increase. But all of this isn’t new. “Srinivasan is too conservative. When it comes to reforms he shies off,” says another source.

There is an interesting story narrated by an individual who was closely associated with the creation of the IPL. “IMG had worked on the IPL for quite some time and had run up a huge expense bill. They presented it to the BCCI and asked them to clear it. Modi agreed immediately but Srinivasan who was the treasurer said no. He said ‘Let them take 10 percent of the revenues’. That was how little faith he had in the IPL. He didn’t think it would be the success it is.”

He’s a bloody buffoon,” is how a Srinivasan supporter described Lalit Modi to us. “If he’s got the guts, let him come back to India,” he added for good measure. Because as things stand now, “Kremlin” Srinivasan is in charge!

During the first two years of Modi’s reign at the IPL, team owners wanted a say on how the IPL was run, with Vijay Mallya leading the charge. But right now Mallya has more pressing matters on hand like cash-flow issues with his other businesses.

The Rajasthan and Punjab teams are in litigation with the BCCI. The Deccan Chargers by all accounts are looking to sell.

As for Mukesh Ambani, insiders say his interests have been taken care of. At the end of IPL 3, all players were supposed to be put up for auctions. But Ambani and Srinivasan wanted to retain their star performers. And that’s what happened against the wishes of the other eight teams.

To that extent, with Modi out of the way, Srinivasan has now has a vice-like grip on the world of cricket, save a single fracas with the flamboyant Subarata Roy of the Sahara group.

The story was covered in graphic detail across media. There are two other versions, neither of which can be corroborated. One version that Roy presented to the media has it that a day before the IPL auctions in Bangalore, Roy met Srinivasan and presented his point of view.

Srinivasan replied, “Most of what happened was when I was not the president.” To which Roy said: “Now you are. You can change it.” But Srinivasan, Roy says, stayed adamant and said: “There is nothing I can do.” Therefore, Sahara threatened to pull out.

But according to sources at the BCCI, Srinivasan and Roy never met. Srinivasan was in Chennai when he got a call from Roy. Roy told him he was going to withdraw if the BCCI didn’t meet his demands. Srinivasan told him it was too short a notice and stayed put.

It was one of the few times that Srinivasan was reacting, not anticipating, like he used to in his “smokestack” days. BCCI has maintained a studied silence on what actually transpired during the entire episode and Srinivasan went on TV to acknowledge that Sahara had indeed been a valuable associate. This most recent episode, in turn, has raised more questions in the minds of cricket watchers in the country.

This most recent episode, in turn, has raised more questions in the minds of cricket watchers in the country.

Srinivasan is caught between two worlds. He needs to come to terms with the new version of the game, which includes the IPL and the CLT20, while the purist in him can’t let go of Tests and domestic cricket.

Problem is, he doesn’t have a concrete plan for either. Why? Perhaps, the answer lies in a question a journalist once asked him about why he didn’t get into the telecom business. “Aasai irunthudu, aana mudiyalai,” he replied in Tamil. Translated, “I had the desire, but not the resources.” Indian cricket fans though know this time around, he has the resources, but does he have the desire?

Srini Speak:

On Why the BCCI is Against the Woolf Report

The Woolf report wants to fundamentally restructure the ICC which is not acceptable to the BCCI. For example, today there are 10 full members of the ICC. All 10 members are represented and have rights on the executive board of directors. The Woolf Report says increase the number of members by two. And then it proposes a board of directors where only four out of the 12 will be directors. They say you have a right to representation, not a right to be on the board. That’s a fundamental point. They say someone else has to represent the BCCI if it is not elected. Then they say that the board will further be made of independent directors.

This is a change that the BCCI is not prepared to accept. There are similar proposals that alter the structure of the ICC as it is today. And that is something that we will not support.

‘BCCI has not lost anything’

BCCI president N Srinivasan says the board will accept the price the market sets for valuations

Are the days of high valuations gone?

Valuations of the products that we have are the

customer’s perception. You can be sure that we will discover that value in a fair, true and transparent fashion. We can’t move the valuation up or down and we have to accept the valuation that comes. It is not a question of saying that you got this valuation some time back and will you get the same one? It’s not a manufactured product and we are not a company chasing an EBITDA.

So we will be satisfied with what we get. We will of course try to get the best; we will create the atmosphere to get that. I don’t say we will get a lower valuation. We will try to get the best.

Beyond that, what is it that we can do?

Do you think ESPN Star Sports overpaid for the Champions League (CL) T20?

I don’t think so. I think it’s an extremely good property. When you start these tournaments, one should have a very long-term view. In the fullness of time, the CL will do very well. The CL is slowly picking up. There are other countries involved. There’s BCCI, Australia and South Africa. The three boards have taken steps to improve the situation. We are getting teams from other countries. There we have delivered all the things. One can’t find fault with us.

You give state associations Rs 15 crore a year. Why aren’t they held accountable?

Associations are sovereign. It is not about control here. What we are doing all the time is that we are encouraging all associations to perform better all the time. BCCI will endeavour to definitely bring best practices. But each state and member is unique. One has to understand that. The structure is a federal one. Each member state association must take that interest and must have that fire to develop.

Lalit Modi has alleged that one man’s ego is costing the BCCI Rs 10,000 crore…

BCCI has not lost anything. This management is capable; it’s straight, clean and honest and will

take care of the BCCI’s interest.

International players not playing domestic cricket…

Our problem has been that the domestic season coincides with visiting teams. It also happens to be the season when we have visits by foreign teams. Therefore, our marquee players have not taken part in domestic cricket. It is also a reflection of the fact that we don’t play cricket through the year. Our weather has a role and in large sections of India monsoon ensures that you don’t have cricket for 3-4 months. When top stars are free there is no cricket in India.

Is it time for a review after an 8-0 loss overseas?

I have said that a review during a tour should not be done. But when they come back I am sure that there will be thought going into the performance, it will be analysed and we’ll see how to go forward. We are aware of what the performance has been and we are a responsible organisation.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)