World Environment Day: India's green conundrum

The government wants to fast-track environment clearances to promote ease of doing business, but this might cause irreversible damage to biodiversity

The government is discussing a proposal to divert 98.59 hectares of the Dehing Patkai reserve forest in Assam (in picture) for a coal-mining project

The government is discussing a proposal to divert 98.59 hectares of the Dehing Patkai reserve forest in Assam (in picture) for a coal-mining projectImage: Samsul Huda Patgiri

R Barooah gave up his corporate job in Delhi 10 years ago and relocated to Assam to take over a tea plantation started by his great-grandfather. The estate is just a stone’s throw away from the Dehing Patkai wildlife sanctuary. Exploring the richness of the forests helped Barooah adopt a slow pace of life. The wilderness is home to a rich habitat, including Asian elephants, Royal Bengal tigers, clouded leopards, crab-eating mongooses, Malayan porcupines, sambars and marbled cats. It is estimated to have about 293 species of birds, 30 different types of butterflies, and over 100 varieties of orchids, Barooah says.

About a month ago, the 42-year-old realised the sanctuary, an integral part of his life, is under threat: Amid the nationwide lockdown, on April 7, the standing committee of the National Board for Wildlife, the highest advisory body of wildlife chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, discussed, over video-conferencing, a proposal to divert 98.59 hectares from the Dehing Patkai elephant reserve forest for a coal-mining project by North-Eastern Coal Field (NECF), a unit of state-owned Coal India Limited (CIL).

Ironically, the approval for the coal-mining project came around the same time when the Assam forest department imposed a penalty of ₹43.25 crore on CIL for illegal mining activities inside the forests of the Dehing Patkai elephant reserve between 2003 and 2019.

Barooah could see the imminent danger, but did not know how to make his voice heard. “When I first settled here 10 years ago, barely two-three cars would pass by these roads. Today, many vehicles, especially coal trucks, can be heard up to late in the evening,” he says. “I have been seeing how indiscriminate industrial activities affect the biodiversity and climatic conditions of this area, which in turn threatens the social security of the people who depend on nature for their livelihood.”

For what it’s worth, Barooah decided to launch an online petition on Change.org to draw attention to the government’s plans. “Within a week, by the first week of May, the petition received over 57,000 signatories. I was not alone,” he tells Forbes India. Towards the end of May, as Barooah’s petition has gathered upward of 75,500 signatures, conservation scientists and student groups expressed concern over Dehing Patkai to Prakash Javadekar, Union minister of environment, forest and climate change.

The Dehing Patkai project was just one of the 31 proposals discussed around the same time, whose implementation would impact about 15 tiger reserves, several notified and deemed eco-sensitive zones, and designated wildlife corridors across the country, and experts have now requested the minister to withhold all other forest and environment clearances during the Covid-19 pandemic.

There has been growing concern over the ministry’s swift clearance over video-conferencing of several large-scale mining, industrial and infrastructure projects located in eco-sensitive zones. In a tweet on April 15, the environment ministry stated these video conference meetings are being facilitated by Javadekar to approve environment clearance proposals “for seamless economic growth during Covid-19”.

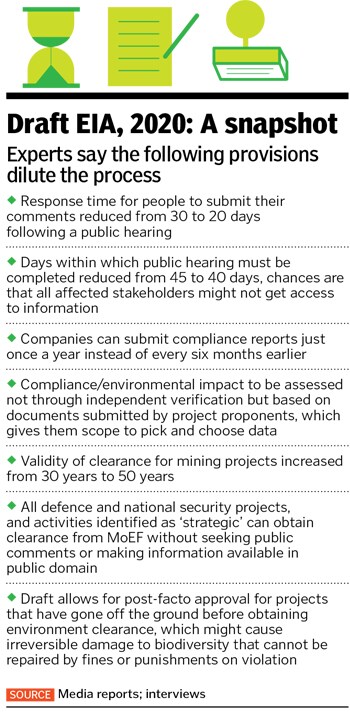

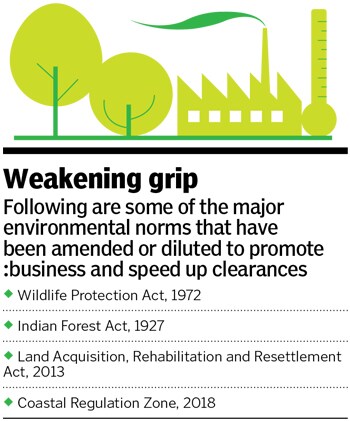

There are also reservations about the draft notification on the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process that was proposed by the Centre right before the lockdown began. Experts believe the new notification seeks to dilute existing provisions on compliance and public comments to speed up environment clearances for industrial development and investment.

According to a May 4, 2020, report in Mongabay, a nonprofit providing conservation and environmental science news, about 145 projects were up for consideration by the Expert Appraisal Committee for evaluation in April and May under the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification, 2006. Some of these crucial projects, according to the report, include building the new Parliament in Delhi, three seaplane airports in Guwahati and Gujarat, a 2,400-megawatt coal power plant at Talabira, Odisha, diamond mines in Panna, Madhya Pradesh, and uranium mining in a tiger reserve in Telangana.

Clearing the way

Forbes India viewed the minutes/agenda of some of these Expert Appraisal Committee video-conferencing meetings uploaded on the Parivesh website of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF&CC). The expert committee is discussing projects via video conferencing in brief 10-minute slots, as opposed to the norm of day-long deliberations; besides there are no site visits during the pandemic. A meeting agenda for the coal mining sector on April 17 also notes that only proposals whose complete details have been received will be taken up during the video conference as the time slot is “very less”.

“The power of clearance can cause irreversible damage to the environment, and this is being done during a lockdown, when the public or stakeholders concerned do not have the freedom to protest or access information about the project to offer their comments,” says Leo Saldanha, coordinator of nonprofit Environment Support Group (ESG), calling the ministry’s activities a “major subversion of democratic decision-making”.

In order to clear industrial projects more efficiently and promote ‘ease of doing business’, the MoEF&CC also proposed amendments to the EIA notification. The EIA is a provision where the environmental impact of an industrial project is considered by the MoEF&CC and attempts are made to minimise it, after which authorities provide a clearance for businesses to undertake their development projects.

The government had first made the EIA mandatory in 1994 under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986. In September 2006, with a view to control rapid industrialisation and climate change, a new EIA legislation was notified. On March 23, 2020, the Centre led by the NDA published a new draft of the EIA notification and invited public comments on the proposal for 60 days till May 22. This timeframe has now been extended to June 30 in view of the lockdown.

Among other things, the proposed draft of the new EIA notification reduces the time given to the public to offer their comments on a particular project from 30 days to 20 days. At the same time, it allows companies to provide compliance reports to the government only once a year, as opposed to every six months at present. There are also provisions that allow post-facto approval of projects that have begun without environment clearances, and also exempts certain activities from public comments or EIA (see box).

“Diluting the EIA and public participation in the environment clearance process gives an impression that the government considers public inputs as an inconvenience and does not believe in the process,” says Kanchi Kohli, senior researcher, Centre for Policy Research.

In a letter addressed to the MoEF&CC on March 24, Kohli and colleague Manju Menon requested the ministry to immediately withdraw the proposed amendments, reissue the draft only after restrictions related to Covid-19 have been normalised, and ensure there are widespread public discussions on the implications of these amendments. According to them, these changes “will have a direct bearing on the living and working conditions of people and the ecology”. Kohli says that even if it delays decision-making, public inputs must be taken into consideration.

Environment vs economy

Experts point out that if promoting ease of doing business is the goal, then instead of reducing public participation, the ministry can address its own procedural delays in granting approvals. For example, according to a 2017 report by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG), 89 percent of all environmental clearances by the MoEF&CC were not provided within the stipulated time period of 105 days. The NDA government has an average delay of 238 days for clearing projects. The report also stated how rampant non-compliance of norms went unchecked: In 56 percent cases, industrial projects illegally cut more trees than they were permitted to.

Time and procedural delays in issuing clearances notwithstanding, the number of projects that have received clearances itself has been high. Between July 2014 and April 24, 2020, the MoEF&CC has approved 2,256 out of the 2,592 projects it received for environmental clearance, according to nonprofit data journalism platform IndiaSpend, with a clearance rate of 87 percent. Of these, around 278 projects are within and around Protected Areas (PA), where human activity is restricted by law, provided it is allowed by the ministry. Richa Sharma and Geeta Menon, joint secretaries of the MoEF&CC, did not respond to Forbes India’s queries on the EIA draft notification and the high clearance rate of industrial projects.

In April and May, the Expert Appraisal Committee took up for evaluation about 145 projects, including the new Parliament House in Delhi. The projects were discussed through short 10-minute videoconferencing and without site visits

In April and May, the Expert Appraisal Committee took up for evaluation about 145 projects, including the new Parliament House in Delhi. The projects were discussed through short 10-minute videoconferencing and without site visitsImage: Yasbant Negi / The India Today Group via Getty Images

In November 2019, Prakash Javadekar—who has publicly maintained that the MoEF&CC can balance business interests with environment conservation—took additional charge as the ministry of heavy industries and public enterprises, a development Saldanha of ESG calls “a direct conflict of interest”.

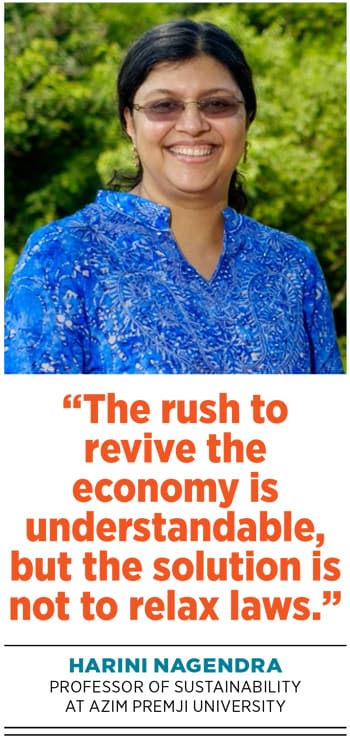

“The rush to revive the economy is understandable, but the solution is not to relax laws, be it related to labour or environment,” says Harini Nagendra, professor of sustainability at Azim Premji University. According to her, the buffer between the economy and the ecology has almost disappeared given that growth is often achieved at the expense of the environment. In the long term, Nagendra explains, this leads to various adverse implications, including zoonotic diseases [which spread from animals to humans, like Nipah, Ebola and the coronavirus]. “The risks of pandemics are increasing because we are encroaching and fragmenting undisturbed forest areas, and increasing human contact with wildlife in the process,” she says.

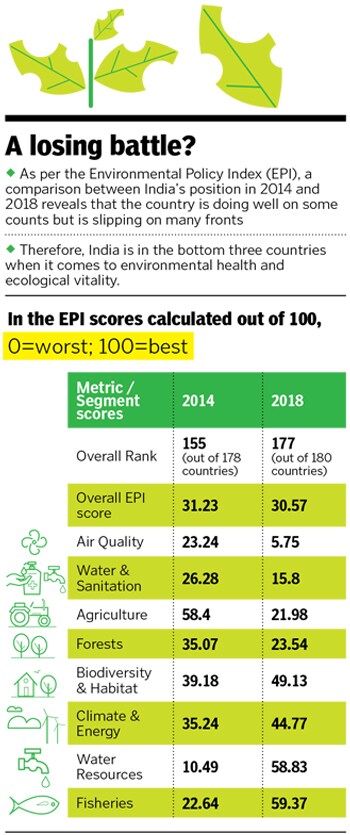

The bi-annual Environmental Policy Index (EPI), published by the Yale Centre of Environmental Law and Policy, ranks countries on metrics covering environmental health and ecological vitality, to measure how close nations are to achieving their environmental policy goals. In 2018, India slipped to 177 out of 180 countries, down 22 spots since 2014. Nagendra believes that lack of inter-departmental cooperation in approving and monitoring industrial and infrastructure projects results in the environment becoming a casualty. “Every government or party just plans for its tenure. The system is incredibly short-sighted on every front,” she says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

A tiger reserve in the Nallamala hills in Telangana may make way for uranium mining

A tiger reserve in the Nallamala hills in Telangana may make way for uranium mining