IIM alumni walk down memory lane

Snapshots of life at the IIMs over more than five decades

The Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs), some of the foremost education institutions in our country, keep popping into our consciousness during placement season (March, for the most part) every year. The salaries students are offered are the stuff of headlines.

But these institutes—the first two of which, in Ahmedabad and Kolkata, were established in 1961—have much more to offer than formal classroom education. The vibrant campus life is as integral to the learning process as the lectures and projects.

We spoke to three members of the IIM alumni, each 20 years apart, to see how the IIMs have evolved since the 1960s.

What we get is a snapshot of each era: These glimpses reflect not just the changing profile of students, but their reactions to formal management education, their aspirations and ambitions, and their approach to life itself.

In many ways, perhaps, this evolution reflects India’s journey over more than five decades.

‘We aimed to change the world’

By Kiran Karnik

1968: The world was in ferment, with massive student unrest and demonstrations in France, Greece and the Red Brigade in Germany, anti-war protests on US campuses, and Vietnam on everybody’s lips. In India, the new Prime Minister was finding her feet and beginning to consolidate her position. Nationalism was considered right, but not Right; along with anti-colonialism, it was then “owned” by the Left. Idealism was in the air. That was the year, 48 years ago, that some 80 of us graduated from Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad (IIM-A), with the exceptional privilege of receiving our degree personally from Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

We had joined in 1966, just the third batch of the Post Graduate Programme (PGP). IIM-A and, indeed, management education in India was new and the Institute was yet to establish a name for itself. We knew little about what the course entailed and, for many of us, even the names of some of the subjects were as strange and outlandish as the campus buildings. And then there was the “case method”, a pedagogic approach that we had never heard of! Coming from an educational system in which speaking in class was a complete no-no, we were now expected to speak up and discuss the cases in class. No more “finger on your lips”; in fact, one was evaluated on the basis of quality and quantity of “class participation” (CP). Grades depended more on daily CP, weekly quizzes and projects, rather than the end-of-term exams. For most of us, this was a radical change, and not one to which we could adapt easily.

Today, these pedagogic methods are widely known. Students go into the IIMs knowing about them and a fair number might have gone through something similar in college. Yet, in retrospect, what we went through—the surprise factor, the discomfort, discovering the unknown—had a charm of its own.

Our batch was the first to join on the then new campus. Our seniors had spent their first year in temporary accommodation outside. We spent our first year in houses meant for the faculty and moved into student dorms only in our second year. Classrooms were in temporary sheds and we braved the Ahmedabad summer (45° C in April) under fans that circulated hot air. Today, the only heat in the air-conditioned classrooms is from the discussions.

The faculty knew almost all students by name and there was an easy camaraderie between the teachers and the taught. This was, indeed, revolutionary: In conventional colleges at the time, there was a vast gulf between teachers and students. Imagine, then, the shock that the institute’s director was not “Sir” or “Professor Matthai”, but just “Ravi”. This would be near-blasphemy in most institutions at that time. Yet, such is the adaptability of the human mind, that we adopted this in but a few weeks. Just as we adapted to the system, the 16-plus-hour workday of the first few months soon eased off to the point when some of us went for matinee shows a few times a week! In addition, of course, to evening visits to the outdoor ice-cream stalls at Law Garden and late-night snacks at Manek Chowk.

No Ola, no kaali-peeli taxis existed then in Ahmedabad, and barring very few, none of us had our own vehicles. Autorickshaws were the primary means of transport and since they generally refused to come to the “isolated and far away” campus, we often used the bus service for our nocturnal forays. However, despite these outings, the campus itself was the main centre of activity. Evenings and late nights saw groups of us sitting around and—like neighbourhood addas in Kolkata—discussing everything from personal problems to the woes of the world. I don’t see much of this now; maybe the students are more studious, or prefer indoor sessions, or the solitude of their rooms. Maybe, in keeping with the times, they are discussing the same issues on online social networks!

Amongst the campus activities was a weekly movie, viewed in an open-air, make-shift “auditorium”. Everyone on campus—students, staff and faculty with their families—would turn up under the clear, star-studded sky. Some faculty members insisted that the Friday night show be shifted to Saturday. My fellow class representative and I insisted that since this was a student activity, it was for us to decide, and not the Institute. This led to a stand-off, and finally (after suffering some surprise quizzes on Saturdays) we had our way, with the faculty graciously relenting. However, neither such issues, nor others, affected the very close faculty-student bond.

Now, I hear, organised movie shows are a rarity, and I doubt if the faculty join even these occasional events. Two other initiatives from our time are worth recalling. One was the Music Room: A record player (and, yes, vinyl records: 78, 45 and 33 rpm) was procured and an eclectic collection of music built up. In the days when most of us heard music only on the radio or in films—with an hour or two a day of Western music, at best, on radio—this was indeed a boon. A few of us also started a student magazine, Red Brick, and successfully brought out a number of issues. It was produced—using the Institute’s facilities—in cyclostyled format. I am sure students of today will wonder what is “cyclostyled” and, of course, the more curious will “Google it”.

We lived on a comparatively small campus, amidst and within Louis Kahn’s iconic architecture—exposed brick-work, gaping holes, few windows. The population on campus has now increased and so has the PGP batch size: From 80-odd in our time to 400 now. Other short-term courses mean about 350 more students on campus. The most dramatic change has probably been the gender ratio: 24 percent in the in-coming batch means 100 women per batch. In our batch, we had one!

Amongst other dramatic changes is the increase in entrepreneurship. In our day, the choices we thought of were a job in an Indian company or one in an MNC (only a few crazies like me thought of the government as an alternative), and no one—bar a few who came from business families—thought of entrepreneurship. Yet, we imbibed the goal of being “change agents” and some of us aimed to change not just the company, but the world itself.

In our days, getting into IIM-A was probably far easier (I doubt I can “crack the CAT” today). Yet, we—the early batches—can take pride in helping create the reputation and brand image that IIM-A has today. That, at least, is what we will convince ourselves of as we from PGP 68 get together in Udaipur to mark the 50th anniversary of our entry to IIM-A. And we would hope that successive batches continue to nurse the dream and make the effort to, indeed, change the world.

The author is an independent strategy and policy analyst, and an alumnus (PGP 1966-68) of IIM-A

‘I was very grateful to get a job’

By Roopa Kudva

I joined IIM Ahmedabad in 1984 and graduated in 1986. There were some landmarks in terms of what was happening in the country—for the first time personal computers came to the campus, the Indira Gandhi assassination took place as did the Bhopal gas tragedy. So, in many ways, it was a very defining period in our history. It was pre-liberalisation, so we belonged to the generation that was just grateful to get a job. Or, at least, I was very grateful to get a job. My first job was in IDBI, where I stayed for six years.

We had a batch of about 180 people; I think we had 19 girls. Only 70 percent of the batch were engineers, compared to today when, in some of the IIMs, more than 95 percent are engineers. So there was a lot of diversity. But, in general, the bulk of students were from the metros. Which, again, has changed; now, students are from all over the country. I came from Assam, where I had a very small-town existence. We were like a minority; most people were from the IITs, big cities, the Stephens, and the LSRs, and the Xaviers.

The first semester is always one of awe and shock, right? You are not used to—at least coming from a non-engineering background—the rigour of daily assessments. You are used to university exams where you cram in at the end of two or three years. The continuous evaluation process is new, and they do pile on the pressure.

But what I most remember from my time at IIM-A was the learning I had outside the classroom. That would be from interacting with exceptionally bright and diverse individuals. There were people who were talented in sports, in dramatics, in writing, quizzing. It was a very accomplished set of people, and just getting to interact with them provides huge learning and insight, particularly for me, who had come from a smaller town. When I had joined, I had had very little exposure to the business world, and had never even heard of Hindustan Lever. Someone had to tell me that it’s the company that makes Dalda and Vim.

One of the things that has changed today is the depth of relationships that we had with our professors; because they lived on the campus, they were very much a part of the community, and it was not unusual to see a professor chasing students in their dorms over assignments; they would sit and play bridge with the students; there was a very strong personal connect, which went well beyond the classroom, which, from what I hear, has changed. Partly because the class sizes have doubled or tripled—in our time it was 180, now it is 400 or 450. It is a totally different dynamic.

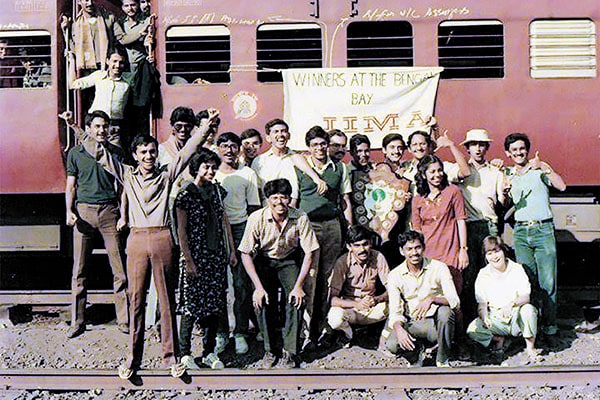

There was a whole set of sports and cultural contests called the Inter-Combos—each group of hostels was called a combo, so Inter-Combo. The talent night was big; the inter-IIM was huge. There were only three IIMs at that time—Ahmedabad, Bangalore and Calcutta. We took a whole train coach and went to Calcutta for the meet. That was great fun! Assam has produced some outstanding table tennis players, such as Monalisa Baruah, so everyone played table tennis! Even I did; not that I was great at it. We didn’t have as many clubs as they have today.

At that point of time there was a sole chaiwalla outside the campus; we’d sit in front of the gate and have that cup of tea. It was a big thing. Today, if you walk out of the gates of IIM-A, you have all these stalls with really good street food. In our time there was no heated water; in winter we would heat our bath water with immersion rods. Today the whole campus is solar-power heated, so you have running hot and cold water. You had one or two phones for all the 360 students. One major feature outside of academics was the queue in front of that one phone. And since we got letters, we had pigeonholes, and you would have to go there to pick up your letters.

There were two important haunts on campus. One was ICP—which was the ice-cream parlour—and they stocked Vadilal’s icecream, which was awesome. The hottest selling variety was Kaju Draksh; it was their No. 1 fast-moving item! We also had music in something called the DJ Room, which was very ornately decorated, outside which you could organise a party, where the badminton court became an impromptu dance floor. And whenever you organised a DJ night, people from the dorms around would pour buckets of water on you. It was part of tradition.

The food in the canteen was good, but everyone loved to complain about it; something I suspect hasn’t changed. But what has changed is the fact that there are so many mobile phones now that you can get food delivered to your room from the stalls outside; and you also now have many more commercially run restaurants on campus. In my time, food choices on campus was limited, or you stepped out to have paratha in the gully outside.

The thing that has not changed is something called WAC—written analysis and communication. You have to write a paper and submit it by 1 o’clock on Sunday afternoon by dropping the paper into a collection box. Students being students, we’d all be scrambling at the last minute. And then, as you are going to drop the paper in the box, the job of the senior batch was to impede you at every step—they would throw stuff, throw water on you. So it was like an obstacle race.

And then, of course, there was the IIM, which was the Indian Institute of Matrimony. A significant percentage of the girls in every class got married to someone on campus. That was certainly true of previous batches too. I don’t know how true that remains today.

Placements were much less important then than what they are today. I think today the summer job itself has acquired much more importance, because if you do well there you automatically get a job offer. That concept did not exist then; there was hardly any linkage between your summer job and your final placement.

The whole focus has changed for a few reasons: It was pre-liberalisation, so the opportunities were limited. You did get the best jobs, and there was enough to go around. The second reason is that it was much less expensive. And that’s a huge factor. Today people are taking massive loans to get the IIM education, and it is important for them that they get high-paying jobs. And thirdly, today’s generation is operating in a market economy, where they are more competitive, and their aspiration levels are higher. People in my time were happy to get what they got and made the most of it.

The author is partner at Omidyar Network and MD of Omidyar Network India Advisors. She is an alumna of IIM-A (1984-1986)

‘I always knew I wanted to be an entrepreneur’

By Praveen Sinha

IIM Calcutta (IIM-C) has a very beautiful campus—it is massive, lush green, has multiple lakes, and is a bird sanctuary in itself. While most may see these as irrelevant attributes for a management institute, it really made me feel that I had chosen the “first amongst equals”. Also, I was sure that I wanted to be an entrepreneur at some point in my life, and hence wanted to choose an institute where the ecosystem gave me the time to reflect on things and pursue my passion. The culture at IIM-C was different from the break-neck speed of a management study routine that I had come to expect.

I remember the first couple of weeks on campus as being really tough for us, with both our seniors and the faculty bringing us up to speed with things.

During the first semester, while everyone was fighting it out with their schedules, I was among the very few to go for walks and sit by the lakes. Later, as my walks became increasingly regular, some seven or eight other students would also come along; but only three or four of them would come regularly. I am from Jharkhand—the ‘green state’—so I was at home amid nature. However, once the all-important CG (cumulative grade points, which could determine our fate in the summer placements) was out of the way, I found many who shared my interest in nature. They soon became my friends. I liked the diversity of the student body, the general atmosphere of the campus, multiple extra-curricular activities, and the calibre of the faculty.

There were lots of clubs on campus, some about culture, others about sports, and more related to academics. Since students could be members of multiple clubs, membership was well-distributed. Clubs related to marketing and finance were quite popular. I was a member of the entrepreneurship club and the NGO club. For the first we organised events and programmes where we invited entrepreneurs to come and talk to us; for instance, we invited the founder of rediffmail. For the NGO club, we were a team of four students from IIM-C who worked with CRY.

To be honest, I knew that at the end of two years there would be an excellent job waiting for me, irrespective of which IIM I decided on. But during those two years, I wanted to have the option of doing what inspired me. I was able to launch my first venture Aquabrim from IIM-C and this was an important step for me. I have never regretted my decision and have never looked back since. I was also lucky to meet my life partner during my campus days, though she was from our sports rival XLRI. We met during our internship at Microsoft.

The night life on campus was always vibrant. We used to spend our time playing various sports, going for walks around the campus or chatting at the night canteen. Every night, the regular canteen on campus would be converted into a night canteen, where we would land up to eat Maggi or omelets. So, while the food was being prepared, we would put in a few rounds of table tennis. This was a nightly feature. Sometimes I would also play badminton.

The best time on campus was during the annual fests—Intaglio and Carpe Diem. Students from multiple colleges from all across India would come. Sport meets with the other IIMs were another great time. The sports meet between IIM-C and XLRI was the most awaited event for us, and was hotly contested. Super seniors like the late Malli Mastan Babu motivated a whole generation of students to take up mountaineering and running.

Although the incubation and innovation centre was not as active as it is now, I never missed any entrepreneurship-related session. We had many entrepreneurs coming to campus and sharing their journeys with us. I always wanted to be an entrepreneur. If I have to give a philosophical reason, I would say that it is a “calling”. But the reality is, I wanted three things: I wanted to build something, I wanted to work with people who are passionate about the work they are doing, and I wanted to be the master of my own time.

While the campus offered a calm and serene atmosphere, occasional trips outside campus used to give us the required dose of city life, with a variety of eating and entertainment options. Apart from the usual ghugni and chai that we got outside campus, one of our favourite hangouts was Park Street. That was one place where even students could afford to eat good food. My favourite place was One Step Up. There was Mocambo as well.

Placements were very important to people in my class, with everyone vying for ‘slot zero’. The two top job options were investment banking and consulting with three or four of the world’s biggest consultants. You could see the pressure building up, and there would be some students who would break down.

To sum it up, Joka (the campus, as we fondly call it) provided a very mature atmosphere which lets people figure themselves out with an incredible balance between a highly competitive and a very collaborative environment.

The author is the founder of Jabong.com, Aquabrim, GoJavas and Pincap. He is an alumnus of IIM-C (2006-2008)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)