On the chessboard, the queen was once the vizier

Many of today's board games go back centuries; they have travelled the world, evolved and become localized

An Alice Through The Looking Glass chess set

An Alice Through The Looking Glass chess setImage: Victoria and Albert Museum Londaon

It is said that, in the 16th century, Emperor Akbar had one of his palace courtyards marked out as a giant Pachisi board, where he used enslaved girls dressed in appropriate colours as playing pieces. You might be more familiar with the game as Ludo, a modern derivative that forms an essential part of every board game compendium today.

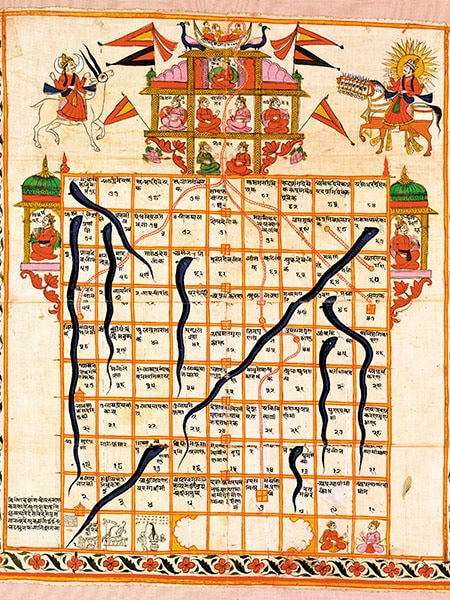

Ludo is not the only board game that originated in India. Snakes and Ladders has been played in India since the 13th century, and had a deeply religious and moral significance with versions played by Jains, Hindus and Muslims, and squares associated with specific vices and virtues, punishments and rewards.

Board games have been around forever, making their way from one part of the world to another, evolving, adapting and appearing in localised versions. Take the example of chess. “The early Indian form of chess, known as chaturanga, had playing pieces reflecting the four main elements of an Indian army—elephants, cavalry, chariots and infantry,” says Catherine Howell, curator of Game Plan: Board Games Rediscovered, an exhibition of board games currently on at the Victoria and Albert Museum of Childhood in London. “When the game reached Europe, these adapted to their new cultural setting, evolving into the pieces we know today—bishop, knight, rook or castle, and pawn. The Raja and Vizier became the King and Queen and the board became chequered.”

A made-in-India Pachisi board from the 19th century

In a world where board games have gone the digital way, Go, a game of space where two players compete to encircle as much territory on the board as possible, has been one of the most complex to programme. The game can be played by two players against each other or by one player against the computer. And though the basic rules are simple, Go, which originated in China about 3,000 years ago, has almost limitless variations of play. According to the exhibition, there are “more possible positions than there are atoms in the known universe”.

In the reverse universe are digital games that have been turned into board games. “In the 1990s, the American company Milton Bradley produced a series of board games based on the most popular computer games—Pac-Man, Zelda, Centipede and Super Mario, among others,” says Howell. “Their target audience was one younger than that which played the video games and the design had to be a simplified version of the real thing.”

A gyanbazi game board with motifs based on Jainism

“In its simple form, a playing surface would be scratched into wood, bone or stone but the same game could also be made with lavish materials. So, for instance, the Egyptian game of Senet has richly made versions found in the tombs of pharaohs and modest forms in clay,” says Howell. “Similarly, in the Middle Ages, games such as chess, draughts and backgammon would be made of different materials to suit the type and class of player.”

By the end of the 19th century, new and easier printing techniques had led to mass production and cheaper goods, making board games more widely affordable. “There was no further need for the laborious process of hand colouring,” says Howell.

Whatever the material or surface, the tradition of playing games remains strong, with the current resurgence resulting in the emergence of games clubs and cafes, a trend that is set to continue and spread. As Howell puts it, “Even if you are the person who only plays a game once a year or so, you cannot help but be affected by the experience. It has always been an important part of people’s lives and long may this continue.”

(Game Plan: Board Games Rediscovered is on at the Victoria and Albert Museum of Childhood, London, until April 23, 2017)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)