Small Print - Literary Magazines

Janice Pariat seeks out literary spaces hidden in small magazines, old and new, print and online

On any given day, Asia Writes, an “up-to-date resource for writers in the Asia Pacific region or of Asian origin”, receives hundreds of calls for submissions from literary journals, both print and online. These they tweet or post for their “followers” — not members of some terribly secretive and archaic cult, but aspiring writers living in the region and beyond. The network may not yet be immense (about 3,000 plus on Twitter and Facebook) but it’s rapidly growing, accurately reflecting how propagative the journal scene is. You only have to browse the ‘Opportunities’ section of the Asia Writes Web site, which provides listings and links, to see how ‘small magazine’ publishing is flourishing. There’s a heady profusion of them worldwide — a Google search for ‘literary journal’ runs into millions — and in India too things seem to be warming up nicely.

Once Upon a Time…

Literary magazines, or ‘small magazines’ (not meant as a pejorative but as a means to distinguish them from big-business, commercial magazines), have been in circulation in the UK, where they first appeared, since the 1800s. The Edinburgh Review, for example, was founded as early as 1802 (its Web site offers a downloadable PDF file of the very first issue), followed by the Westminster Review in 1824 and, more famously, the right-leaning Spectator in 1828.

In the United States, among the oldest and most prominent literary magazines are the North American Review (founded in 1803) and the Yale Review (1819). The latter, published by Yale University, included contributors such as Virginia Woolf, Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens, Eugene O’Neill, H.G. Wells and John Maynard Keynes.

The movement gathered strength in the 20th century: Poetry Magazine, published in Chicago from 1912, has grown to be one of the world’s most well-regarded journals (it featured one of T.S. Eliot’s earliest, and most famous, poems, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock); and even those who have only a passing interest in the literary world would be familiar with the London-based Times Literary Supplement that first appeared in 1902.

With the rise of the independent press in the mid-20th century, the number of small magazines rapidly increased. Small magazines also executed substantial literary influence; The Kenyon Review, for instance, published in Ohio, USA since 1933, is considered to have embraced and shaped New Criticism that dominated Anglo-American literary criticism at the time. This period also saw, in 1951 in London, the founding of Nimbus, “A Magazine of Literature, the Arts, and New Ideas”, widely regarded as an important cultivator of English modernism, while across the channel, The Paris Review was started in 1953 for, as advisory editor William Styron wrote in the founding issue, “the good writers and good poets, the non-drumbeaters and non-axe grinders. So long as they’re good.”

The idea, of course, was to provide space for the marginalised, the new, the uncommon. And that could well be the agenda of all small magazines, no matter where in the world they are published: To promote literature — in a broad, all-encompassing sense of the word — through poetry, short fiction, essays, book reviews, literary criticism and biographical profiles and interviews of authors.

The Hungry Generation

In India, the small magazine gained strength in the culturally rich atmosphere of the 1950s and 60s in a movement to publish literature in regional languages.

In Bengal, there was an invigorating, small magazine culture, beginning with Kallol, published in 1923 by a group of young writers including Premendra Mitra, Kazi Nazrul Islam, and Buddhadeb Basu. It was followed by journals such as Kabita and Parichay. Yet, the truly exciting period was the early 1960s, the time of the Hungry Generation, a literary movement launched by Shakti Chattopadhyay, Malay Roy Choudhury, Samir Roychoudhury and Debi Roy. This group challenged accepted norms of expression, opting for experimental content and forms. The movement had wide-reaching consequences, influencing Hindi, Marathi, Assamese and Urdu literatures. The 1970s saw the “Kaurab cult” with the publishing of the cultural magazine Kaurab. A number of cult figures, such as Swadesh Sen, Kamal Chakraborty, Barin Ghosal, Debajyoti Dutta, Pranabkumar Chattopadhyay, Shankar Lahiri, Shankar Chakraborty and Aryanil Mukhopadhyay (the current editor), are associated with it.

After experimental, modernist poet Bal Sitaram Mardhekar burst into the Marathi poetry scene in the mid-1940s, a number of “laghu aniyat kaleek” or small non-periodical magazines — both ephemeral and long-lasting — sprang up in the next three decades. These included Shabda (published by reputed writers Dilip Chitre, Arun Kolatkar and Ramesh Samarth), Vacha, Aso, Bharud, Lru and Rucha, which featured the non-conformist, anti-establishment and radical writings of well-known Marathi poets, including Namdeo Dhasal, Vasant Abaji Dahake, Vasant Dattatreya Gurjar, Vilas Sarang, Tulsi Parab and Manohar Oak. The Marathi little magazine movement lost momentum in the 1970s and 1980s, but a resurgence in the 1990s saw the founding of journals Abhidhanantar, Sausthav and Shabdavedh. According to the Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Marathi Literature, “The focus of these magazines is their insistence on locating contemporary Marathi poetry in the context of the tremendous social changes that have taken place due to globalisation and the policies of the Indian Government like liberalisation and privatisation.”

Little magazines continue to play an important role today in preserving indigenous literature and providing a platform for regional writers.

It is not the same, however, in English magazines. Their history has been more slow and sporadic. In the 1960s, there was Poetry India, where Nissim Ezekiel was editor (1966-67). New Quest, a quarterly journal of literature and culture, was launched in 1977, and in the late 1980s, The Quest, an English journal showcasing criticism and essays on Indian writing in English and regional languages, was launched.

Yet, it cannot be denied that their numbers are rising. Antara Dev Sen’s The Little Magazine, devoted to essays, fiction, poetry, art and criticism, has been running since 2000. Kritya, an international journal of contemporary Indian and world poetry, published its first issue in June 2005, as did Muse India, an e-journal with the objective of showcasing Indian writings in English and in English translation. Nether, a quarterly magazine for English literature from Mumbai, was launched mid-2010. Most recently, we have Reading Hour, which began in January 2011. It is a bi-monthly magazine for short stories, poetry, essays, book reviews and more, primarily by freelance Indian authors.

What’s the Big Deal?

Yet how, if at all, are small magazines significant in the Indian literary scene?

As Rahul Soni, co-founder and co-editor of Pratilipi, a bilingual online literary magazine, says, “New media platforms make it possible for newer sorts of writing to find a voice, an audience, to take risks that established publishing houses with their overheads and bottom lines may shirk.” This might explain why the greatest impact small magazines have had in India is on poetry: Mainstream Indian publishing houses have a diminished, and dwindling, poetry list. Anindita Sengupta, a Bangalore-based poet, says it’s only novelists who have literary agents and publishing houses “running after them”. Sumana Roy, a writer based in Siliguri, who “[grew] up on a literary diet of Bangla little magazines of various kinds”, thinks that it is only in the pages, real or virtual, of such magazines that poetry, for one, will survive. Apart from that, upcoming writers are also given a platform to share their short stories, graphic stories and experimental fiction alongside established names.

From the selection process involved, it’s clear that small magazines are willing to push literary boundaries.

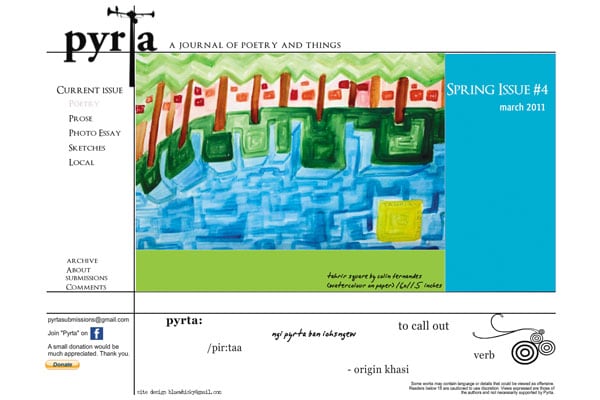

Ambika Ananth, editor of Muse India, says she prefers contemporary everyday realities and insightful social observations to narratives that are “trying the tried and hitting the hit”. At Out of Print, founding editor Indira Chandrasekhar says their story choices are informed by the issue of living in an era of intense and accelerated transition that may destroy the diverse, yet common narratives that link us. Although only two issues old, it has featured a fine selection of stories including pieces by Mridula Koshy and Anjum Hassan. Pratilipi, around since 2008, has a long, illustrious list of more than 350 contributors from 25 languages, including Keki Daruwala, Rana Dasgupta, Ashis Nandy and Indira Goswami. According to co-editors Soni and Giriraj Kiradoo, “At the end of the day (or night), we look for voices that engage us, writers dealing with their language and content without the mediation of dominant ancestral or contemporary voices — qualities, therefore, of freshness, vitality and essentiality.” The third issue of my own publication Pyrta has featured one of Vietnam’s most well-known poets Nguyen Quang Thieu alongside young, upcoming names such as Himali Singh Soin, Arielle Nelson and Arka Mukhopadhyay (recipient of the Toto Funds the Arts Creative Writing Award 2008).

A New Life, Online

The Internet has drastically changed the dynamics of print publishing, providing relatively cheap cyber space and introducing ‘print-on-demand’ services. More and more little magazines are now launched via a Web site, and perhaps foray into print later, if at all. The Web makes for easier production and dissemination, making online publishing more sustainable.

Pratilipi co-editor Giriraj Kiradoo is hugely optimistic: “Online magazines have only recently begun to make their presence felt. But they’ll soon (in a decade, perhaps) replace their print counterparts, many of whom have begun to realise this and are making themselves available online. One of the oldest lamentations in the scene is that Indian writing in Hindi and other indigenous languages needs better exposure and representation, for which the new platforms are ideal: They are free from both the clumsy charity of the state, and the lazy myths of the mainstream publishing.”

Ambika Ananth, editor of Muse India, agrees. “Online magazines seem to be a viable option today with their cost effectiveness, easy accessibility and easier archival storage — better preservation and restoration of material. Print has its limitations. There has been a boom in contemporary literature, thanks to small magazines, or it can be seen as vice versa.” And, as Rati Saxena, editor of bilingual poetry magazine Kritya, points out, there is now “increased space for expression.”

Sustainability is easier online, but there is also the issue of quality control: Cheap virtual space is more prone to mediocre, sub-standard writing. Although, journals, as compared to say, personal blogs, offer curated content, practically anyone with little or no experience can style themselves ‘editor’ of an online literary space.

What’s the Problem?

The Internet-powered surge has coincided with a rise in sub-cultural spaces in various urban centres like Yodakin in New Delhi, which stocks independently published and produced books, music and art. Alternative groups such as Madness Mandali in Mumbai, comprise amateur and professional poets, painters, designers, photographers, musicians and theatre troupes who invite people who “don’t think straight… intentionally”. There is a profusion of open mike events in various cities, not to speak of a flurry of literature festivals. All these provide a sense of community for writers. They also provide word-of-mouth information, an informal platform and distribution network for small magazines, which usually cannot afford to pay for advertising and publicity.

But does this rapid rise in our access to ‘alternative’ literature herald a burgeoning English literary scene in India, similar to the one in America a few decades ago?

Not at this point perhaps. Indian small magazines in English are still niche, their readership does not begin to rival that of bestselling novels; they haven’t yet garnered the respect and literary authority and quality that, for example, The Paris Review, demands.

Also, since they are relatively new, there is no guarantee of longevity. Chennai-based poet Sharanya Manivannan has her reservations about small magazines in print: “I’m not optimistic about their future. These things have a tendency to peter out owing to problems with distribution and funding (as is the fate of many books that come out with small imprints).” Sumana Roy has other suspicions: “I think most, if not all, of these magazines would like to go commercial at some point, and therein lies my reservation. Much as I’d like to see poetry turn into a profit-making enterprise, I’ve seen how revenue-earning becomes tied up with canonisation so that a subterranean culture that litmags are so often host to are gradually marginalised.”

But Rahul Soni, co-editor of Pratilipi, is optimistic. “Indian writing (especially in English) has a lot of coming and a lot of ageing to do. The magazine publishing trend in the US coincided with the rise of a generation of new, astonishingly talented writers, and communities of writers; we have not arrived at that synchronicity yet, but one gets the feeling that we are on the cusp of something similar.”

Where’s the Money?

Small literary magazines don’t have much of a life expectancy. Many fell by the wayside, more victims to financial constraints than to the ravages of time. But many new ones spring up, inspired by pretty much the same reasons as their predecessors in other countries, regions and centuries: A labour of love for the written word, with the editors putting themselves out of pocket, not to mention the time and passion each issue demands.

Pratilipi manages by offering a print-on-demand service, which means readers pay for the print copy they order. As Rahul Soni and Giriraj Kiradoo, its editors, succinctly put it, “[the online edition] costs less than what we [the three editors] spend on cigarettes. But that’s perhaps a gross understatement of the amount of time and passion that the magazine has demanded from us in last three years.” Still, they say, “We have been lucky in that we haven’t faced the usual problems: Lack of readers and response, unavailability of quality material, and the attitude of ‘big’ writers.”

As Ambika Ananth says, “Literary magazines are easiest to start and toughest to run.” Muse India, she says, meets publication expenses through the “monetary contributions of well-wishers. Relying on grants, patrons and advertisements are the only solutions, and to get them, content quality and circulation has to be sustained.”

For Rati Saxena, the struggle continues: “[Until now,] we do not have funding for Kritya, I have to do things myself, I still do not know where we can get some help.”

It is difficult to harness high quality writing or artwork for a literary magazine as contributors are largely unpaid. Yet, somehow, these tenacious little magazines continue to be sustained, whether through windfall luck or sheer will power. Yet, against all odds, and despite world wars, economic crashes and recessions, dwindling readership and worthy contributors, they endure.

Ambika Ananth is happily optimistic: “The number of enthusiasts for small magazines ensures their thriving presence in the market. Small magazines are here to stay. They control and canonise popular literature.”

Indira Chandrasekhar, of Out of Print, an online platform for writers of English short fiction with a connection to the subcontinent, puts it eloquently: “I believe that the intense need for a greater number of publications that is driven by writers, and more significantly by readers, must result in increasing the numbers of well-run, consistently-edited, high-quality publications with their individual and distinct voices.”

It is difficult to offer a well-rounded, comprehensive analysis of the impact of small magazines in English on the Indian literary scene. All that can be said is, they’re young, vibrant, enthusiastic and helping to generate a national, and sometimes even international, network of creative people.

One thing is for certain: To lose our small magazines will mean to silence a tremendous number of voices. In what is perhaps the best case for the defence, Chandrasekhar quotes Junot Diaz: “My sense of it is just that we desperately, desperately, desperately need more stories, and 99.9 percent of the stories we need to access our humanity aren’t available to us.”

(Janice Pariat is a freelance writer and editor of Pyrta)

Why I quit smoking

That clichéd stuff about labours of love? At times the two don’t go together, labour and love. There are nights when I scowl into the computer screen wondering why I do this. I hate it. It’s driving me mad. I need a cigarette. Then dawn breaks. The poetry page is done; it looks beautiful. And I’m in love again. Online literary journal editors are horrendously fickle.

When people ask me why I started Pyrta, I try and think of a fittingly wholesome and noble reply. The truth? Well, they say writers write the books they want to read, I started Pyrta in July 2010 for the same shallow, selfish reasons. I wanted a beautiful online space — not just in terms of content but also style — and I couldn’t find anything out there that I particularly liked.

Seriously, though, Shillong, where I live, has a number of established authors including Kynpham Singh Nongkynrih and Robin Ngangom (both are editorial consultants for Pyrta), yet no platform for young, upcoming writers; we encourage young local writers to contribute. We edit their work and offer suggestions. It’s a small community, but it’s growing. Pyrta features work by people from across the country and the world. We’re trying to put together as many different voices as possible in the same space; like a small literary or cultural festival.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)