The drama of discontent

The creative expressions of protest theatre take on many forms, but remain true to their fundamental premise of raising a voice

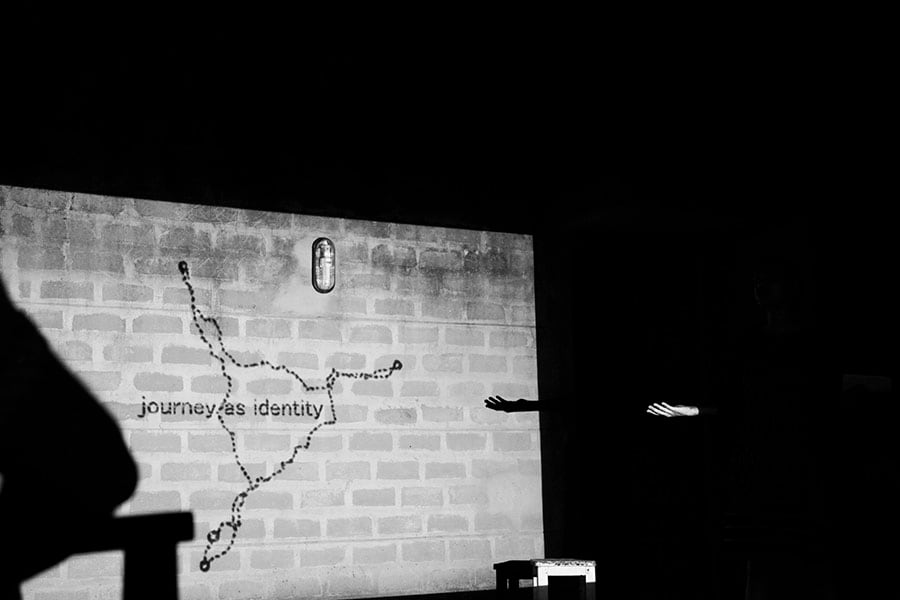

The troupe members of UR/Unreserved travel across the country to bring forth issues that affect the hinterland

The troupe members of UR/Unreserved travel across the country to bring forth issues that affect the hinterland

Courtesy: UR/Unreserved

Protest theatre has existed for ages, in myriad forms, seeking to overcome social ills and bring about change through performance. The protest theatre of the 1940s, for instance, played an important role in India’s struggle for independence. It is always interesting to observe how each new zeitgeist heralds its own cycle of protest theatre, with old methods of resistance and agitation giving way to new forms of engagement, even as traces of historic struggles linger in each wave of politically-charged creative expression.

This year, on Gandhi Jayanti, under a banyan tree in Bengaluru’s historic Cubbon Park, a green expanse of 300 acres that is often dubbed the “lungs” of the city, a unique theatre initiative was flagged off for an epic pan-Indian journey. In the wee hours of the following day, 14 troupers boarded the New Tinsukia-Bengaluru Weekly Express to begin the first leg of UR/Unreserved, a collaboration between locally based Maraa Collective, a media and arts organisation, and 44-year-old project director Anish Victor. “We will be ready to work as soon as the people start waking up,” said Anish purposefully, as his team embarked on an expedition that would take them along hand-picked arteries of the Indian Railways, India’s veritable nervous system.

Eight members of his team, or the performer-facilitators, would try to map out notions of identity, both personal and communal, by interacting with passengers and train personnel on a ‘performative’ journey with clearly defined rules of engagement. They would be accompanied by assorted crew members, a visual artiste and Anish himself. The circuitous route would take them to locations as far-flung as Dhemaji in Assam, Srinagar in Jammu & Kashmir, and Irinjalakuda in Kerala, all nodal points near the country’s extremities, identified as venues for ‘Platform 1’ events. These events—performance pieces, songs, installations or films—would be a sharing of findings from each concluded leg of the train journey.

Theatre practitioners, ensconced in their echo chambers, are often alienated from the issues that beset the great amorphous hinterland. UR/Unreserved’s desire to reach out to a large and diverse cross-section of people—an estimated 10,000 people in 30 days—and return with a patchwork quilt of identity and belonging almost smacks of naïve idealism, but there are deep reserves of conviction that fuels it. An excerpt from the project’s press release indicates the kind of stories that inspire it: Referring to the 2012 exodus of North-Easterners from Bengaluru, it says, “The images and stories of women, children and men fleeing in thousands on trains, with their hurriedly gathered belongings, was the starting point for the idea of UR/Unreserved”.

Courtesy: Agent Provocateur

The geographic span of the project was dictated by the access afforded by Anish’s connections, as well as those of Maraa and local collaborators. For instance, in Assam, Dhemaji-based Macbeth Drama, one of the few groups in the country working to preserve indigenous culture, had hosted Anish’s solo performance, Koogu, at their festival Under The Sal Tree in 2014; they were happy to come on board. As was Kashmir’s Help Foundation, which has worked with victims of conflict for almost two decades and view theatre as a means for catharsis. “There are no public spaces in Srinagar. The military has occupied most of it,” says its director, Nighat Shafi, and hopes that UR/Unreserved would help create much-needed spaces for expression and dialogue.

In a later phase, yet undecided, the project will tour with a travelling exhibition to different public spaces. According to the organisers of UR/Unreserved, “These will be publications, short films, podcasts, sketches, maps, photographs curated to strengthen and deepen our engagement with students, artistes and the general public.”

******

In September, Anish first assembled his team in the town of Thiruvalla in Kerala. Prospective candidates considered to be most grounded in the regions to which they would travel were selected, with an emphasis on creating a diverse group with shared passions. There are four pairs of performer-facilitators, one each from Karnataka, Assam, Jammu & Kashmir and Kerala. Building a cohesive unit keeping in mind their disparate sensibilities and cultural backgrounds was the first challenge thrown Anish’s way. He was clear that he did not want to dictate affairs, but, instead, draw out the ensemble’s ideas and experiences to shape the project’s modus operandi on the trains. “In an exercise that is about solidarity more than anything else, foregrounding one person’s vision doesn’t make sense, because we are talking about identities that keep shifting from person to person,” he said.

Initially they had thought of moving from coach to coach, using games, pop-up acts and songs to foster a playful and congenial space where conversations could thrive, even in settings as shape-shifting as train compartments. But they later decided that it would be much more conducive for the team to fan out across the train, in twos or threes, as ‘invisible’ actors gathering insights and encounters.

Image: Godrej Culture Lab

Anish’s exercises with his actors involved intensive self-reflection. “We looked at biases and stereotypes within ourselves. We are so conditioned to the outside, we often fail to see what is going on inside,” he said. This led to the strands that each performer-facilitator wanted to pursue on the trains. For instance, Goutham Sahadevan, the youngest performer from Thrissur, would observe the changing identities of places—trains, platforms, the geographies they rumble past. Mouchumi Borpatra Gohain, from Assam, was interested in identity and gender. Another performer-facilitator would look at workers on the train—attendants, vendors, pantry staff, the omniscient TTEs—while a fourth would analyse how technology is linked to identity.

Although this approach also had the unintended outcome of breaking down the railway ecosystem into neat categories, the performers were not interested in creating a representation of the populace they would encounter, but observing how they themselves were affected by the interactions. Depending on the region they were travelling in, performers with relevant language abilities would spearhead the initiative.

For the facilitators, changing the modus operandi from being a travelling performance to an undercover investigation with a far-reaching scope certainly required a leap of faith. As each pair trawled the train, they would seek spontaneous entry points into existing conversations between passengers and veer the talk towards their own thematic preoccupations. The material would later be collated and transcribed.

On the first train journey itself the team faced several challenges: Plugging into conversations around the chosen themes proved difficult at times; they couldn’t enter the unreserved compartments and sleeper coaches because of the teeming crowds; and pantry folk and vendors were too busy to interact.

Yet, there was fertile ground for conversations, like among the people huddled around compartment doors hoping to share seats. Being artistes allowed Anish’s team a kind of incipient privilege, the novelty of their profession piquing the interest of fellow travellers. “We spoke to all kinds of people. What was surprising was that people were generally quite open to share testimonies,” says Anish. “The biggest challenge was figuring out how to put it all together. At Dhemaji, we tried to consolidate the journey’s learnings with writings, testimonials and art, but much work still remains to be done.”

“ The images and stories of women and kids fleeing in thousands on trains was the starting point.

One of the encounters on the train was with a man from Siliguri. “He shared deeply personal issues. He had lived in different cities for work. His body was covered with scars that were like a map on his skin. He could remember places through his injuries, which were mostly occupation-related. He had worked as a security guard, as a metro personnel, whatever he could plug into. His nails were raw and bruised from labour. He was happy to make the journey home because it meant he could finally rest,” says Anish.

This tapestry of lived experiences indelibly imprinted on a person’s body finds echoes in a set-piece from a dance theatre performance called Agent Provocateur, directed by Sujay Saple, in which the body as a site for resistance finds expression. (Disclaimer: This writer of this article was the project’s co-dramaturg.) The play opened in Pune this September before runs in Mumbai and Bengaluru.

The scene in question features performer Surbhi Dhyani as a seemingly docile woman in pristine white, dicing beetroot on a cutting board, even as she smears herself with mashed pulp of the beetroot. A man (Arpit Singh), possibly her lover, sneaks in from behind, carrying a sheet of bindis. He then proceeds to stick bindis on various parts of her body as she reels off names of towns and hamlets—Srinagar, Kuruskshetra, Ballabgarh, Muzaffarnagar—each associated with personal memories that become even more insistent when the exercise is repeated again and again. It is soon clear that the bindis on her body represents a map of recent lynchings in India. The beetroot in her hands could well have been beef. Dhyani then launches into a frenetic dance of fury and defiance. It is a visual motif that speaks for itself.

Even within Anish’s project, the politics of meat became a flashpoint. In Dhemaji, where pork is almost a staple, the Kashmiri collaborators wouldn’t partake in the sharing of bread. “There was tension within the group. We realised that some things are so deeply entrenched and so sensitive that divisions can very suddenly become palpable,” says Anish. “It is so easy to say we must live and let live. But I actually don’t know what tolerance means sometimes. Why should anyone tolerate anything?”

Saple’s work takes on similar conflicts, albeit in different contexts. It is an activism he is still grappling with because his earlier works have all been calculatedly apolitical. “If you work out of a place that is going through conflict, are you expected to address it through your work?” he said in an interview to The Hindu. So, while Anish and his cohorts’ reaction to these perturbations of the soul have brought about a prodigious grassroots excursion, other theatre practitioners in cities are participating in the mainstreaming of protest in their own ways, mindful of their own detachment from the issues they feel compelled to take on.

For instance, in a scene from Agent Provocateur, Dhyani emerges from the wings outfitted completely in saffron—hipster rags, an orange wig, even lipstick to match. She sings into a mic, as if in a karaoke bar, the song being John Lennon’s ‘Across the Universe’, with altered lyrics by co-dramaturg Rachel D’Souza. It is an anthem of pitiable apathy, even as it seemingly plugs into a protest culture that is more about being trendy than about the integrity of an authentic social consciousness. It was Saple’s way of training a mirror on his own contradictions, and that of others of his ilk.

For various reasons, however, this scene extracted the most complaints from viewers, prompting Saple to excise it entirely from his narrative. Some complainants saw it as reductive and jarring because it undermined Agent Provocateur’s larger message of a call to revolution, which is likely to be infinitely more gratifying.

Theatre-maker Neha Singh thought otherwise. “For me, the image of this confident girl singing this ridiculous song is a symbol of how we are today,” she says. Singh recreated the scene at rehearsals for her upcoming play, Jhalkari, which seeks to restore an icon for the dispossessed who have been erased from history. The play’s eponymous character was the Dalit chieftain in Rani Laxmi Bai’s women-only battalion, who also stood in as the queen’s battle-charging decoy.

Among recent works that have joined forces with these murmurings of demurral is Sunil Shanbag’s Words Have Been Uttered, a sharing of staged writings around the idea of dissent, cutting across cultures and geographies, to present it as a universal ideal. Shanbag prefaces the performance with a short spiel, “At this point in our history it’s really important to understand the need for something like dissent, the role it plays, and the issues associated with it.” The scope of the production includes everything from lesbian writing to Bhakti poems, from Bob Dylan ballads to nazms by Habib Jalil, from Palestinian poems to Rohith Vemula’s last letter. The title is taken from a poem by the destitute Dalit poet, Lal Singh Dil, dubbed ‘The Poet of the Revolution’ for the Maoist movement in Punjab.

Courtesy: Words Have Been Uttered

A no-frills presentation by Shanbag allows us to contemplate the words as stark and socially meaningful. Even an episode from a classic text like GP Deshpande’s Uddhwasta Dharamsala, translated by Shanta Gokhale, seems likes a page from a contemporary treatise, as a Leftist professor (Jaimini Pathak) is called before a hastily convened college tribunal and adjudicated on his political affiliations. The threat to progressive values so palpable in the 1970s, when the play was written, remains as topical to this day. Similarly, Gokhale’s new play, Menghaobi—The Fair One, provides a wistful take on Irom Sharmila, remaining steadfastly at the side of the erstwhile icon of public resistance even after her so-called abdication of the struggle against the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act.

Earlier this year, at the International Theatre Festival of Kerala, the brutalisation of Dalits was brought out for public airing by a raw and powerful street theatre piece. Directed by activist Ramachandran Mokeri, the production was titled I am Rohith Vemula. At the outset, the cadaver of a polystyrene calf was butchered, and its bloodied entrails distributed to onlookers like an offering. Clad like a vintage-era rock star, Mokeri strummed his guitar as he led a procession through Thrissur’s busy streets, quoting from Vemula’s last letter in a guttural voice relayed via loudspeakers. Accompanying him were actors, in various stages of undress, branded with black markings. Their keen dark eyes glinted with deprivation, and their lips were a trembling red. Some were dragged across the road, others were lashed. The two-hour procession certainly registered with onlookers as a powerful reminder of atrocities that otherwise no longer shock. The people on the streets clapped and cheered and raised slogans, mirth mingled with awe at the theatrics, but perhaps they also took home some of the pain and the agony.

The seeds of discontent have seen the emergence of marginalised voices and the showcasing of their expression on mainstream podiums. For instance, the Godrej Culture Lab in Mumbai has recently hosted protest organisations like the Kabir Kala Manch and Yalgaar, Dalit rock bands like Dhamma Rocks, and folk artistes like Sambhaji Bhagat, in day-long seminars that included discussions and performances in which the collisions of worlds was papered over by open-hearted exchanges.

Relaa, a collective of such activists and groups from several states, started functioning a couple of years ago and hosts an annual jamboree, which has taken place in Delhi and Mumbai. They are part of a burgeoning people’s movement seeking to target mainstream audiences and the youth. The groups harness folk forms, interspersed with songs and commentary, and work with working class/lower middle-class populations in different states. At the Culture Lab event, Yalgaar, a group of men in their twenties, presented excerpts from their repertoire, where their founder, Dhamma Rakshit, said, “We are cultural warriors striving for human liberation. Our weapons are the words bequeathed to us by Tukaram. We want to keep the diversity in our world alive, but any kind of discrimination must stop.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)