The Interesting History of Bourbon Whiskey

Bourbon's history blends smoothly with that of the United States itself

Recently, I caught up with a friend at one of Delhi’s better watering holes. While my friend stuck to his favourite pint of beer, I decided to test the cocktail skills of the chap behind the bar, and ordered an Old Fashioned. I cherish my Old Fashioned. In fact, this is the one drink I’d be happy to replace my morning coffee with. It is one of the simplest recipes known to any bartender worth his ilk; yet it is incredibly complex, and difficult to perfect.

Mixed for the first time in the 1880s at the Pendennis Club in Louisville (looh-a-voul), Kentucky, this cocktail calls for a combination of ice, sugar, bitters and rye whiskey. Rye? Yes, the original grain that went into the first examples of whiskey that were distilled in America. And, Jack Daniels was not the first one.

The story of bourbon is probably the story of the United States of America. It begins with the arrival of the first colonists—Spanish, French, German, Irish, British and Scottish—in the early part of the 17th century. With them came the art of distilling. These early settlers put their knowledge to judicious use, as the new land challenged them with a change in raw material. From brewing with barley and fermenting with grapes in Europe, they turned to rye, corn and apples.

Beer was drunk in copious quantities. The reason was simple: It was cleaner and safer than water. (Could we brew some ‘barley water’ at home, given the acute paucity of drinking water we face?) Rye was, by far, the most extensively used grain during this period. Corn came in much later, when people realised it grew faster than rye, and had a higher yield. Apples, too, were available in plenty for the settlers to distill applejack brandy from.

The easy availability of molasses and sugar from the Caribbean islands meant that rum, too, was being distilled in the US.

The Whiskey Rebellion

At this point in history, the slave trade was at its peak owing to the ‘Trade Triangle’ between colonies in Africa, the United States and England. It was a time of turmoil and great change, and the distilling industry in America found itself, willingly or unwillingly, woven into the dramatic economic, political and social development of the country.

The American whiskey that we know of today began to develop only around the 1770s. This was the time when the early settlers were reeling under the burden of oppressive taxes levied by the British colonists. What was it that was being taxed? Among many other things, alcohol. Disgruntled distillers started moving away from the colonies of Pennsylvania, Carolina, and Georgia into fertile lands next to Virginia that would later be recognised as the state of Kentucky.

The seizure of a ship, The Liberty, at the Boston harbour while it was trying to smuggle in stocks of alcohol to evade taxes (the practice was, and continues to be, known as ‘rum running’) was an event that set the stage for rebellion.

The ship was owned by none other than John Hancock, one of the wealthiest men in the 13 colonies, the first governor of Massachusetts, and, as the president of Congress, the first signatory of the Declaration of Independence.

The following years were bloody and violent. Every war has a price to pay, and this one was no exception. Soon after becoming the first president of the United States of America, one-time distiller George Washington, and his treasurer Alexander Hamilton decided to levy taxes to repay the debts of war. Ironically, taxes were the very reason the country had gone to war in the first place.

Distilled spirits were the first to get taxed. This, obviously, didn’t go down well with the locals, and families engaged in distilling moved from their homes into forests where they would distill by moonlight. The illegal alcohol thus produced came to be known as ‘moonshine’. This was then sold to dealers—bootleggers—who would hide their contraband inside their boots.

This infamous ‘Whiskey Rebellion’ came to an end in 1794.

Distilling down the ages

In honour of the services rendered by the French during the American War of Independence, Bourbon County was so named in 1785. So was the town of Louisville, where whiskey was distilled in 1783 for the first time by Evan Williams.

A clergyman named Reverend Elijah Craig is also a significant name in the history of this native spirit. This Baptist minister distilled his whiskey in Bourbon County, and transported it to New Orleans on flat boats down the Ohio to the Mississippi. On one such journey, he filled his freshly distilled ‘white dog’ (unmatured whiskey) in charred white oak casks that had earlier held pickled fish. Little did he realise that the liquid inside the cask would turn delightfully golden after reacting with the charred wood in the warm southern summer.

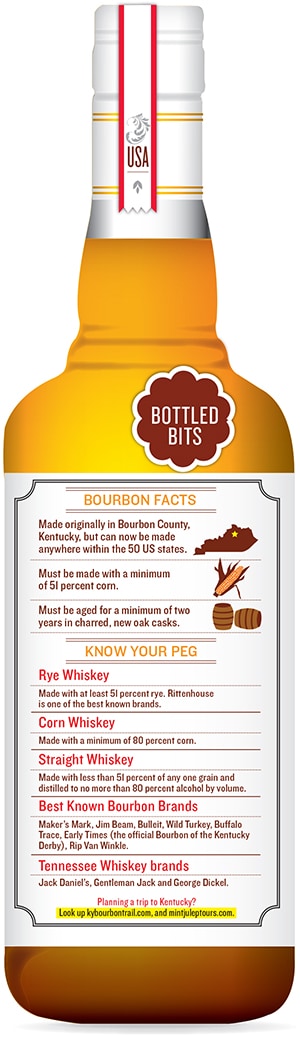

Craig might have been happy to know that today bourbon whiskey is required, by law, to be matured in charred new oak casks for a minimum of two years, and has to be made with at least 51 percent corn. Corn is preferred for being one of the most widely grown crops in the US.

What really intrigued me was the fact that a barrel cannot be used more than once for maturing American whiskey. So, when I met Even Andrew Kulsveen, owner of Kentucky Bourbon Distillers that produces Willet bourbon whiskies, I couldn’t help but ask him why. Well, legend has it that the law for using new oak casks only once was put in place by people who had massive interests in the barrel making business (cooperages). But freshly made bourbon gathers maximum character from a charred new oak cask in its first fill. There is no mistaking that.

Today, America is the leading supplier of used oak barrels to the spirits industry throughout the world.

The scotch whisky (notice the difference in spelling) industry, for one, gets more than half of its barrels from the US. This holds true for the rum industry in the Caribbean, and the wine industry in South America. A handful of Indian spirit manufacturers also feature on the list.

Over the past 50 years, the bourbon industry has been on an upswing, creating nearly 10,000 jobs, and generating more than $125 million in taxes each year. But things were not always this way.

However, all the whiskey that comes from America is not bourbon. Tennessee whiskey comprises a small percentage of the total production figure. The ubiquitous Jack Daniel’s is a Tennessee whiskey. How is it different from Jim Beam bourbon? Tennessee whiskeys follow an extra step of filtering the whiskey through a 10-foot layer of maple wood charcoal. What follows is the sour mash process: The practice of retaining a bit of residue from a previous batch of fermented grains to kick off fermentation in a new batch of grain mash. This, producers argue, helps preserve continuity in flavour, and is a common practice in the industry today.

Law, lawmakers and bootleggers

History has often found whiskey distillers on the wrong side of the law. The more control the government exercised, the more they took to illegal distilling and avoiding taxes. There was a time when there was hardly any control over the quality of liquor that was being produced. Spurious alcohol found its way to people’s homes, leading to mass alcoholism. Eventually it gave rise to the Temperance Movement that fought to ban alcohol.

By the 18th Amendment to the American Constitution, also known as the Volstead Act, prohibition came into effect from January 16, 1920. It banned the production, sale and consumption of alcohol. With this, Detroit became the centre of illegal booze production, spinning an industry worth $250 million. Canada opened its otherwise dry laws to allow alcohol production for export purposes only. Rum running and bootlegging were on a never-before high.

Fortunes were made. One such bootlegger, Joseph Kennedy, who exported alcohol to the United States from Canada, amassed a huge fortune, and went on to join the ranks of the most illustrious American dynasties. Years later, his son, John F Kennedy, made his way to the White House as its 35th occupant.

But, things spiralled out of control with the Great Depression. The people who once advocated prohibition, now asked for its repeal. With the 21st Amendment signed by President Franklin D Roosevelt, the prohibition ended in February 1933. However, eight states—Nebraska, Kansas, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Georgia and North and South Dakota—did not repeal the prohibition, and some counties within these states remain dry till today.

Over the decades, production techniques have become increasingly refined, and big brands have given way to smaller boutique ‘small batch’ producers. Bourbon tourism has seen a massive growth in the past few years with the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, a tour to the heart of America’s distilling industry. It has attracted well over two million visitors—including domestic ones—in the past five years.

When will one of India’s indigenous alcoholic beverages be marketed as an experience? For a liquor market that runs neck and neck in size with the United States, I wonder what we are waiting for. All in good time, one hopes.

As for you, the next time you run up a cold sweat while ‘rum running’ a few bottles of scotch (or maybe bourbon) from Pondicherry or Chandigarh, think of those first-time settlers, and know that you will be raising a toast to the fascinating history and lineage of bourbon whiskey itself.

Rohan Jelkie is senior manager, Beverage Education & Training, Tulleeho Portals

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)