Theatre sans Frontières: India emerges as an attractive destination for foreign troupes

Collaborative works with foreign theatre troupes form cultural melting pots, but there remain constraints and concerns for Indian players

Theatreconnekt was the local producer of the second leg of Hiroshi Koike’s retelling of the Mahabharata in 2015

Image: O Ajithkumar

In 2014, Neel Chaudhuri, the artistic director of the Delhi-based Tadpole Repertory, was a delegate at the Performing Arts Meeting (TPAM ) in Yokohama, Japan, a frenetic arts festival for theatre and contemporary dance that showcases cutting-edge works from across Asia and beyond. It also functions as a veritable trade expo—the M in the acronym initially stood for Market—in which international festival curators swarm theatres, studios and warehouses, hoping to discover the ‘Next Big Thing of the Orient’, or perhaps just a curate’s egg that would appeal to the Western audiences they cater to.

Chaudhuri wasn’t entirely sold on this culture of relentless fraternising, but he was able to soak in the shows on offer. This included Yojo X (Girl X), a technologically augmented theatrical experience that relayed a compelling sense of the digital zeitgeist of Japan’s gadget-obsessed generation. “I found the work oddly familiar and was drawn to its aesthetics, which was minimalist yet layered,” Chaudhuri says. Interacting with the crew of the play paved the way for a future association with Suguru Yamamoto, the wunderkind director behind Yojo X, and his company Hanchu-Yuei.

Image: O Ajithkumar

This matching of sensibilities was particularly gratifying because Chaudhuri had discovered that the perception of Indian performing arts even in a snazzy international forum such as TPAM still bordered on the quaint and the exotic. Delegates would ask him about the masks he used, or the performances that took place all night long in India, as is customary only to some traditional forms. “They were pleasantly surprised by Tadpole’s portfolio of contemporary innovations,” he says.

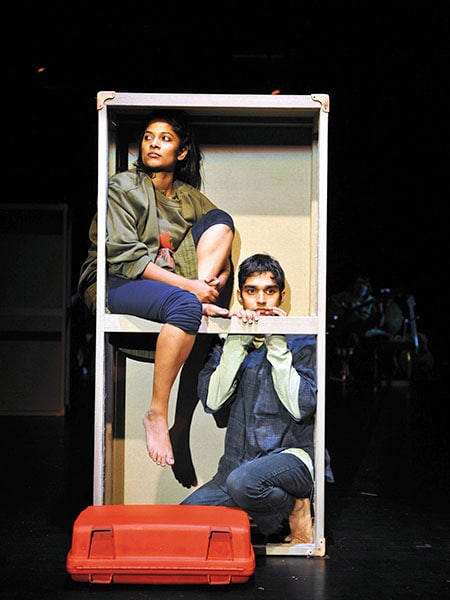

Earlier this year, This Will Only Take Several Minutes, a play written and directed by Yamamoto and Chaudhuri, and performed together by their respective troupes, toured several cities in India. Although its Japanese and Indian ensembles perform in different languages, an overlap is achieved by a shared preoccupation with urban ennui and the sapping loneliness that is so markedly a feature of modern living, and common to both Delhi and Tokyo presumably.

The collaboration was not without its hiccups. An initial workshop in Delhi in 2015 organised by the Japan Foundation, one of the prime movers behind the project, proved to be a non-starter. “There were issues of translation; members of Hanchu-Yuei spoke little English,” says Chaudhuri. Yet, they persevered and, finally, a month-long process late last year resulted in a piece that married Tadpole’s contemplative storytelling with the instinctive approach of the Japanese performers.

Image: Tadpole Repertory

It did make for a seamless experience on stage, with a rare beauty and an essential humanism, even if some of its elements seemed to require further development. Hanchu-Yuei have since returned to Japan, and given the logistical constraints of effecting this creative interaction between people in countries separated by several time zones, it is debatable if more shows will be performed in India.

Collaborations between theatre troupes in India with those from other countries have multiple outcomes; the biggest, of course, being the creation of a cultural melting pot. Not only do these provide enriching experiences for the audiences, but also for the troupes themselves, who come from backgrounds with varied work cultures, narratives and performance styles. The role that Indian theatre companies and personalities play in these collaborations differ, with some being the local partner responsible for logistics and others having creative positions with a hand in the conceptualisation of the play.

Since 2008, the Thrissur-based International Theatre Festival of Kerala (ITFoK) has served as an arena for artistic communion, even if its raison d’être is not so much to facilitate networking as it is to upgrade audience sensibilities in Kerala. The international selections have brought in contingents from across the world, thus revitalising Kerala’s theatre immeasurably.

Last year, Munich’s Volkstheater invited Kerala-based auteur Sankar Venkateswaran to stage Tage der Dunkelheit

Last year, Munich’s Volkstheater invited Kerala-based auteur Sankar Venkateswaran to stage Tage der DunkelheitImage: Susanne Brill

Yet, the gains from this climate of intercultural exchange is often frittered away in the year-long gap between editions. For this reason, a few theatre practitioners set up the non-profit Theatreconnekt in 2013. “The local scene has greatly benefited from the philosophies and professionalism of the international troupes. We wanted to formulate ways to take this forward,” says Kesavan PN, one of the group’s founders. In the ensuing years, Theatreconnekt has facilitated several international co-productions.

In 2015, it was the local producer of the second leg of Hiroshi Koike’s retelling of the Mahabharata, a mammoth production spanning several years and four countries, each hosting one chapter of the epic. After showcasing the first chapter in Cambodia in 2013, Koike travelled to India to create the second chapter Vanaparva, or the story of the Pandavas in exile. Indian actors were added to a multicultural cast, including the Malaysian butoh performer Lee Swee Keong and the Balinese mask dancer Koyano Tetsuro of Japan. “I don’t have any difficulty with differences in culture because my work is broken down to what a performer can create with his body,” says Koike.

The local team was astounded by the visiting troupe’s work ethic. Chandran Veyattummal, the Malayali music composer, was roped in and given an extensive production handbook, in which every detail from the third bell to the climax was mapped out to the very last second. Music for each interlude had been placed in a scheme that catalogued parameters such as duration and mood. Veyattummal had never been accosted with such a meticulous blueprint and he faithfully delivered the requirements. On their part—and especially after a trying first leg in Cambodia marred by production mishaps—Koike and his team were disarmed by the professionalism of their Indian counterparts, and the streamlining of pace and process.

Kesavan, however, looks back at the project with mixed feelings: “The Mahabharata ‘as it is’ exists in our collective memories. The Indian team should have had a creative role in the conceptualisation of the production rather than just being used as a production facility.” According to him, Koike’s version was merely representational of the epic and did not match the expectations of local audiences—the ensemble also toured internationally—who were keen for a reinterpretation.

But it must be noted that Koike’s vision had been crystallised during a period of great disaffection: In recent years, Japan has been roiled by a stagnant economy, rising neo-fascism, an earthquake and the subsequent nuclear disaster in Fukushima. It was a karmic cycle that seemed to be straight out of the Mahabharata, at the end of which almost everything is destroyed.

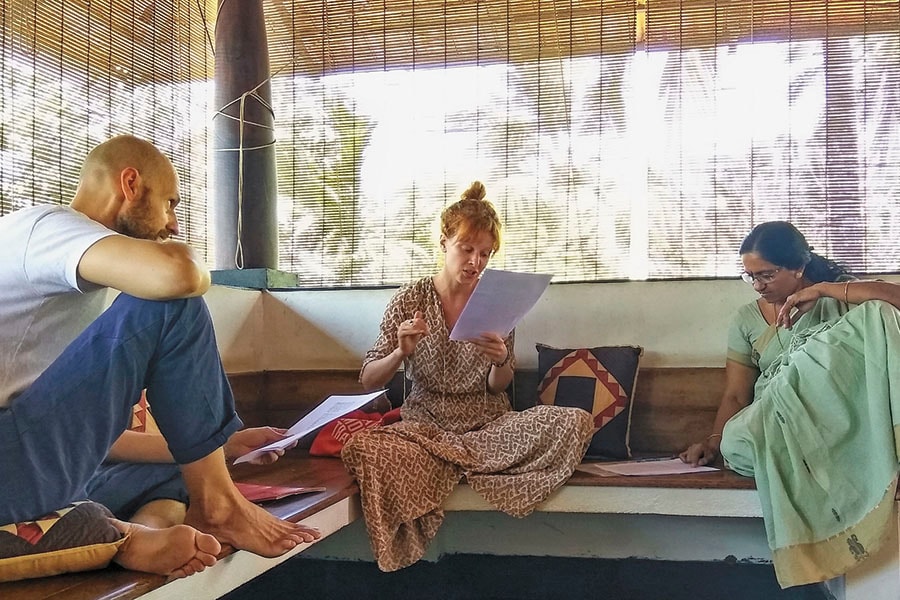

Playwright Ivan Vyrypaev (left) with actor Karolina Gruszka (centre) and Usha Nangiar

Playwright Ivan Vyrypaev (left) with actor Karolina Gruszka (centre) and Usha NangiarFor the final post-war apotheosis of the epic, Koike may once again touch Indian shores next year. And although Kesavan is amenable to working as its production manager, he would do so at an individual level, and not under the aegis of Theatreconnekt.

Theatreconnekt’s latest project, Not our Business…???, is a street play made in conjunction with Art Junction Poland, and opened at this year’s edition of ITFoK. Directed by Jarosław Siejkowski, it was planned as a response to the helplessness the director felt after reading Martín Caparrós’s eye-opening book, Hunger, last year. Hailed as a masterpiece of literary reportage, the book’s English edition is slated for a release this October.

Siejkowski started work with an ensemble of mostly Kerala-based actors, but his initial idea was waylaid when improvisations threw up strong Indian motifs of discrimination and oppression, expressed with a sincerity that fits in with the street theatre ethos of relating with the immediate audience. Finally, he decided against imposing a structure that could be perceived as culturally alien.

“Siejkowski is an accommodating individual who was ready to operate under any constraints, without demands,” says Kesavan. Siejkowski had helmed another Indo-Polish piece for ITFoK’s 2014 edition, which was a festival showpiece and did not tour. In contrast, Not our Business…??? is slated to tour in Kerala extensively later this year.

The French play Une Chambre en Inde, which drew from Indian performance traditions, was made during a residency in India, supported by the local group Indianostrum

The French play Une Chambre en Inde, which drew from Indian performance traditions, was made during a residency in India, supported by the local group IndianostrumImage: Michèle Laurent

The other international project Theatreconnekt has sparked off is the highly anticipated collaboration between the Russian playwright Ivan Vyrypaev and Nangiarkoothu exponent, Usha Nangiar. The genesis of this project has been slow and long-drawn. An initial meeting was arranged last August in the temple village of Chathakudam, followed by another extensive meeting there this February. Vyrypaev’s writings employ simple social language, but possess deep spiritual underpinnings. In Nangiar’s work, he was able to discern the inheritance of an ancient knowledge that, according to him, potently described the very nature of being.

Eighty days have been earmarked for rehearsals, beginning with a 15-day schedule in July, with the piece slated to open in Poland in 2018. Kesavan doesn’t miss the snappy timelines usually associated with Indian projects: “This is a meeting between maestros. It is not easy to get the link in between. Ivan has a busy schedule, and Usha likes to tread carefully before committing to an idea.” After all, Nangiar is the custodian of an ancient form, and the specific use of koodiyattam (the most ancient form of Sanskrit theatre, of which nangiarkoothu is the genre performed only by women) in this exchange is still to be figured out.

Unlike Kesavan’s experience with Koike, where Theatreconnekt’s role wasn’t clearly defined, Mumbai-based Q Theatre Productions (QTP) takes a more informed decision while engaging with international theatre companies. QTP acts as the local producer, and enters a project only after roles and responsibilities are clearly mapped out; its involvement, however, often exceeds the defined parameters. “We end up taking a bigger role by virtue of being from the host city, with a huge bank of knowledgeable resources to draw from,” says Toral Shah, QTP’s creative producer.

Shah and her team enable the visiting troupe to negotiate the local ecosystem, whether it be with hospitality management, publicity, or technical support. Shah had cut her teeth as an assistant stage manager for Tim Supple’s sumptuous multicultural A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which was commissioned by the British Council in 2006 and had a celebrated international run.

Tadpole Repertory’s Piyush Kumar in a scene from This Will Only Take Several Minutes, directed by Suguru Yamamoto and Neel Chaudhuri

Tadpole Repertory’s Piyush Kumar in a scene from This Will Only Take Several Minutes, directed by Suguru Yamamoto and Neel ChaudhuriImage: Tadpole Repertory

In 2013, French director Éric Vigner’s Gates to India Song, based on the writings of the legendary Marguerite Duras, was produced by QTP for the Bonjour India festival. Shah recalls how Frank Thevenon’s lighting design, with its intricate tapestry of tints and glints, needed to be achieved with the often limited inventory of lights available at Indian venues.

“It’s the kind of thing for which a local hand was needed to execute and pull off with whatever was available. So, it’s almost like we are ‘theatre translators’. The director has a vision, but to recreate it in Indian terms requires intercession on our part,” she says.

In Kolkata, the play was performed in the courtyard of Rabindranath Tagore’s 18th-century home in Jorasanko. It was a homecoming of sorts, since Duras’s novel, The Vice-Consul, an inspiration for the play, is set in colonial Calcutta. The entire venue needed to be built from scratch without disturbing the sanctity of the heritage site. Vigner came with a clear vision but, as Shah says, “They were very open-minded about what they may find in India, about what we think and how we work. They hugely depended on us to guide them.”

QTP were also line-producers onboard the Edinburgh Fringe Festival sensation Nirbhaya: Breaking The Silence during its limited run in India in 2014. While director Yaël Farber was a strong leader in the room, she had an openness to hear the local crew out, thus engendering a cross-cultural collaboration. On these projects, the QTP team has been exposed to different approaches to creating theatre. “Even months before the casting takes place, the sets and costume design and technical specifications are ready,” says Shah, mirroring Theatreconnekt’s experience with Koike. It is a telling contrast to the lifecycle of a play in India, where the script and actors are almost always the starting point, with everything else coming in later.

When producing an international show in-house, like they did with Adura Onashile’s HeLa in 2014 and the international offerings at Thespo, the youth theatre festival, there are several adjustments to be made along international conventions. For instance, foreign performers, who are usually members of an actors’ equity group, need to be compensated in line with their industry standards (although this is negotiable). “Their working hours are often pre-defined, with a day off that we have to observe. We can’t have consecutive days of matinees or more than two shows in a day, so that is certainly new territory for us,” says Shah.

A Boy with a Suitcase—featuring actors Pallavi MD and Shrunga BV—is a collaboration between Mannheim’s Schnawwl National Theatre and Ranga Shankara in Bengaluru

Image: Nationaltheatre Mannheim / Schnawwl

India is definitely coming up as an attractive new destination for international theatre practitioners with its burgeoning infrastructure, its exotic-but-upgraded appeal, and the advancing calibre of local theatrewallas. However, it is plagued by the absence of a systematised arts funding regime that could subsidise similar excursions by Indian artistes abroad. A weaker currency adds to the handicap.

International troupes benefit from the support of embassies looking to extend their soft power. Organisations such as the Institut Français en Inde and Alliance Française (they produced Gates to India Song), the Japan Foundation (it promotes Indo-Japanese partnerships) and Pro Helvetia India (it supports Indo-Swiss works) are all important conduits for cultural interchanges.

India’s chief cultural export, however, remains Bollywood and classical dance forms. Indian funding organisations, like the India Foundation for the Arts (IFA), could hypothetically come on board for the odd international co-production usually in partnership with foreign agencies who would bear the cost of international travel, according to Shubham Roy Choudhury of the IFA’s Art Practices programme. The IFA is legally bound to only provide financial assistance to the India-based component of a project. It always makes better financial sense for the building of a work to be carried out in India. Similarly, annual financial grants for the performing arts from the ministry of culture are not enough to fund an extended international sojourn.

QTP, for instance, tries to cover costs with crowd-sourced fundraising, or through consular support. Since ticket collections are meagre, some of these ventures are looked upon as investments. The group is always striving to support high-concept works that push boundaries, but which are sufficiently portable to become viable touring productions in India.

Yet, there are the usual suspects who have made inroads into international circles. For instance, Sankar Venkateswaran, the Kerala-based auteur, who has a résumé that is chock-a-block with foreign collaborations. Last year, Munich’s Volkstheater invited him to stage Tage der Dunkelheit (Days of Darkness), a mostly non-verbal adaptation of Bhasa’s Urubhangam from fifth-century BC, based on the last day of the decisive battle of Mahabharata. In late May, Venkateswaran will premiere Indika at the same venue. This is a project of grand scope and great substance, piecing together the history of Chandragupta Maurya, during whose reign much of India was administered as a politically organised centralised state. Both productions, featuring German actors, were produced by Volkstheater.

Similarly, Abhishek Majumdar and his Bengaluru-based Indian Ensemble travelled to Western Africa’s Burkina Faso last July, to collaborate with Ouagadougou’s Théâtr’Evasion on a global theatre project that aims to research perspectives on human trafficking and work exploitation. Supported by the German Federal Cultural Foundation, the project, dubbed The Human Trade Network, with parallel productions in four countries, will be showcased at Baden-Württemberg’s Theater Freiburg in June.

The regularity with which these co-productions are being announced speaks of an arts universe in which barriers are being broken down to get to the other side. In the best of times, theatre in India can be likened to several parallel cultures, so the impact of this cross-pollination will likely be first seen in those spaces that display an openness to diversity and a global outlook. Even within the country, theatrical output rarely transcends region, class, language or any other cul-de-sac of choice. To throw yet another component into the mix brings in a counterpoint that will perhaps find its own privileged niche, which could well be an end in itself.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)