Money Matters Around The World

Every country manipulates currency to ensure that its economic model doesn't get hit. In today's world that may not be such a good idea

Pop band Dr. Alban’s hit single ‘It’s My Life’ struck a particular chord with most people around the world with its message of individual sovereignty. Unfortunately when world leaders say “It’s my currency”, it draws hostile reactions. That’s why when Brazil’s finance minister Guido Mantega said a few months ago that “We’re in the midst of a currency war”, he had everybody’s attention. Mantega was referring to how countries were cheapening their currency to export their way out of the economic slump. Naturally, each nation’s central bank carved a different path — adopting exchange rate controls, import controls, or a tighter monetary policy. China, Japan, Argentina, Poland and even Brazil kept the value of their currency down.

But isn’t this much leeway allowed to a nation when local jobs and economic wellbeing are at stake? Harvard University economist Richard Cooper says, “Unless a country is negligibly small, its exchange rate policy is legitimately of interest to its trading partners.” That is why he is strongly against countries manipulating exchange rates directly. Instead, he advises central banks to indirectly manage exchange rates through monetary policy.

At the heart of the problem is the US dollar, once rock solid but now nearly kaput in value. Emerging market countries are crying foul that the Federal Reserve is printing too much of its money, thereby cheapening it. The problem is compounded by the fact that countries like China have invested their massive trade surplus in dollar-denominated assets, which is now tanking in value. The other concern is because the price of money in the US is next to nothing, all those dollars are being invested in emerging economies for higher returns. So in effect, the US is exporting inflation to emerging markets, which are already fighting against the build-up of asset-price bubbles triggered by strong GDP growth.

Nobody is taking any action. “Everybody wants everyone else to take action. [That’s what’s happening between] the US and China, for example. Obviously the truth lies somewhere in-between,” says Raghuram Rajan, economic advisor to the Indian Prime Minister and professor, University of Chicago.

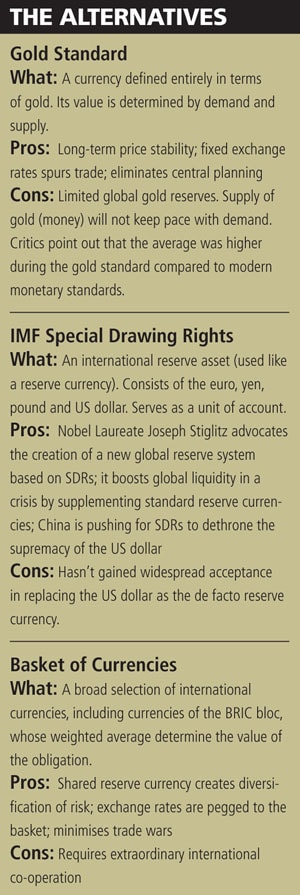

The global monetary system is under serious strain. At the heart of the tussle is the amount of money each country can print to meet its economic policy objectives. Long ago, this decision was simple because each country’s currency was backed by gold. If a country wanted to print more notes, it just had to increase its gold reserves. In 1970-71, the dollar went off the gold standard. Pretty soon everybody was following one of three systems. Some like the US adopted a floating exchange rate regime, allowing supply and demand to determine the value of their currency. Some like China decided to peg their currency to the US dollar, which they bought and sold to maintain the fixed value of their currencies. Others like India followed a flexible exchange system where they would intervene on a case-by-case basis to make sure that their currency stayed within a band.

Bart Van Ark, chief economist at the Conference Board, says, “India has effectively kept its economy within the boundaries of solid growth without letting the growth run completely out of hand.” It appears that at least in the short-term, India must sing along to the popular rap number Do What You Gotta Do — which in its case is to fight inflation without killing exports and starving infrastructure of precious capital inflows.

It appears that at least in the short-term, India must sing along to the popular rap number Do What You Gotta Do — which in its case is to fight inflation without killing exports and starving infrastructure of precious capital inflows.

But even a nation of many-handed gods can’t juggle all things at once.

“You can’t obviously target interest rates and exchange rates, and have free movement of capital as well,” says Marti Subrahmanyam, professor of economics at New York University, referring to the open economy dilemma. “Right now, finance minister Pranab Mukherjee says India will not discourage capital from coming in. That’s easy for him to say. But the RBI is not comfortable with that statement because they’re the ones fighting inflation. Ultimately India will need some sort of hard or soft capital control. There is no other way.”

Still unleashing capital controls is creating all sorts of market distortions. Plus critics point out that it hasn’t made much of a difference in Brazil. So in the short-term, it appears that India and other emerging market economies must resort to a tight monetary policy regime. In the long-run however, the appetite for holding reserves in US Treasury bonds has to diminish. As of September 2010, India held $41 billion in Treasury bills.

“Why should countries hold more and more US debt, especially if the dollar keeps on depreciating?” Subrahmanyam asks. But the dollar’s position as the de facto reserve currency is well entrenched. Measures to move away from it haven’t worked quite as well.

Kathy Lien, director of currency research, GFT, New York, says, “Peace will come when growth returns. Right now, everyone is internally focussed,” she says. “The message that the US is sending is that without recovery in America, all other countries will suffer.”

(Additional reporting by N.S. Ramnath )

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)