Service Complexity: Managing A House Of Cards (Really)

Whether Lean principles can help us chart a path through the complexity and actually improve customer service?

It may make sense to offer 12 varieties of lattes, at least to the company that markets the offering. In most cases though, too many choices create complexity and frustrate the customer. Moreover, there are times when the offering flummoxes the company’s staff. Slimming and streamlining the offering is the way to go, says this author, who suggests 3 practical steps an organization can apply to simplify things.

So, my daughter is going to Europe with her school’s travel club for a week over March Break. It’s an event that’s stressful enough for parents as it is, but then we start thinking about things like spending money, shopping and markets. Admittedly, those are topics of conversation for my wife and my daughter. I thought the idea was sightseeing, history and culture. But, what do I know?

We came around to a reasonable amount of money in cash (Euros), and agreed that a credit card with a low limit on it would be appropriate. My wife went into the bank where we have banked since the days when you needed a passbook and knew the tellers by name (I won’t name the bank here). That’s just when the situation became frustrating. She explained our needs to the customer service representative, who politely responded that the bank didn’t have a card for a 15-year-old. They went back and forth a bit, my wife explaining that we didn’t want a separate account – our daughter obviously has no credit history – just another card on our account, in her name, with a distinct limit. This seemed very reasonable to us, and we expected, something that people asked for all the time. But nope, nothing. “You’re telling me you that have no product that can help me?”, my wife asked. “Correct,” was the response.

At just that time, one of the personal bankers happened by (don’t ask me about the bank’s hierarchy, although that’s related to the story). The CSR turned to the PB, looking for confirmation of her position. Fortunately, the PB asked my wife to tell her what she was hoping for. She repeats the request, and the PB says, “We can do that.” We thought we were off to the races. Well, almost. A number of gyrations, stalls and calls later, my wife and daughter picked up the new card the Friday before the big trip.

Full disclosure: this isn’t a customer service discussion, (although it could be). The issue here is complexity, and managing that complexity in a customer-centric environment. Specifically, the issue is whether Lean principles can help us chart a path through the complexity and actually improve customer service? The answer is, “Yes,” but there are challenges.

Problem Number One: Banks today simply have too many products and services for front-line staff to be aware of and understand, let alone master to the point of properly explaining the various options to a customer.

Problem Number Two: Bank tellers are a blend of part-time and full-time employees, and turnover ranges between 20 and 50 percenti. Think about that – in the row of 5 Customer Service Reps at your local bank, at least two of them have likely emerged from training in the last several months.

Problem Number 3: Through the Internet, referrals, and discussions with friends, family and peers, customers likely know more than the banks do about their products and services. Put all this together and no wonder banks struggle for solid customer service ratings. The deck is stacked against them, and by their own design!

Some might suggest that the problem is related to a lack of training for front-line staff. Well, yes and no. A few months ago, my accountant suggested that I get a corporate credit card for my little enterprise. After poking around the bank’s website, I found what I was looking for and tried to apply on-line.

“We’re sorry – that product must be applied for in-person at your branch.”

OK. As it turns out, our bank’s policy is that any new business accounts or changes to existing corporate accounts are managed by the branch manager. We had to book an appointment. When we arrived, two days later, we found that the manager wasn’t familiar with that particular card. But we worked through it. He was a nice guy so we decided to give him the benefit of the doubt. But again, we realized that there were just too many products and services for anyone to be an expert on any of them.

In my class last month I ran an exercise with a group of MBA students. Each student had to select a service where they had experienced a very good or very poor encounter sometime in the last 6 months, and then discuss the circumstances. There were a number of telling statistics that came out of the exercise, but interestingly, as many people complained about banks as airlines. The bankers out there are probably shocked: “You’re comparing us to an airline?” Actually, “Well, no. Your customers are.”

The revolution of lowered expectations

This was an anonymous exercise, so it wasn’t a matter of people jumping on a ‘Beat the banks’ bandwagon. We generally know what to expect from airlines and air travel…regulatory issues, security, cost, delays, co-passengers. As consumers, we’ve been trained to believe that a trip that arrives pretty close to on-time – and with all of our bags — is a great trip. But banks? I really believe we all expect more.

If complexity is the issue, where does it come from? For starters, take a look around your house. You’re probably like the rest us, a pack rat. We never throw anything away. Who knows when we will need those copies of Beverly Hills Cop I and II on VHS in our basement, those old shot glasses in our cupboard that we pinched in our university days,, or the worn-out hockey equipment on the shelf in the garage? I don’t know, but we will need them!

It happens in companies too, where all the old stuff — legacy products or services – is very difficult to dump or wind down. We are deathly afraid of alienating the 3 percent of our customers who still use them. Gasp! What if they are upset and go to the competition? Worse yet, some of the rarely-bought or rarely-looked-at stuff on our offering menu is there because of our attempts to innovate were never finished. We liked an idea, rushed it through, and now that 1.0 version is enjoying marginal adoption. But we’ve moved on to the next good idea. Most 1.0 ideas don’t really work, but we launch them anyway.

What else drives the holding on to legacy services? Long-term customers locked into something they signed up for 15 years ago, something that we no longer offer to new customers. My parents had this account called a Full-Service Plan with Bank of Montreal way back in the 1980s. They loved it. It was an all-in account with great interest rates, chequing, a safety deposit box, and a maitre’d of their very own every time they came into the branch, all for something like $6.95 per month. BMO hated it – it didn’t make any money on that account. After a couple years, it stopped offering it, and every time my parents went in, staff tried to convince them that they should “upgrade’ to some new account.” Dad said “No,” and they stuck with it for years. Banks have dozens of these types of accounts around, sustaining complexity.

Executives are reluctant to wind down existing revenue streams, even when they know something better is coming along. Don’t alienate the existing customers, we need those revenues! As well, our information technology systems are now equipped with such mammoth storage potential that we keep every piece of data we’ve even thought of over the last 15 years. And it’s cheap. What if someone offered to turn your two-car garage into an eight-car garage for almost no money? How much stuff could you store then? It starts to sound like a George Carlin nightmare.

So, we’re too complex. There’s too much stuff, too many services, and not enough expertise to manage it all successfully. How do we fix it?

The answer comes down to understanding what our customers really want. This is the first step, and it really is the toughest. What does our customer really value, and what can we get rid of? If front-line employees in a bank don’t understand all the credit cards we offer, maybe we have too many? Perhaps the customers don’t really need that many?

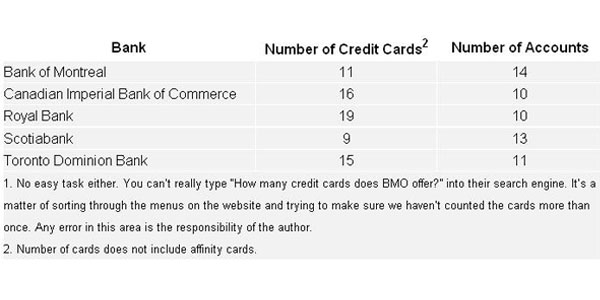

We did some quick research on the Big Bank websites (see the table below). Based on what we could gleam from the Internet1, Royal Bank, for example, has 19 different credit cards, while Scotiabank has nine. There are cards such as Gold / Platinum, Value, No-Fee, Low Interest, Dividend (cash back), Student, and others. And this is before we even think about some of the affinity cards that are out there, like the card offered in conjunction with your alma mater. Bank accounts? BMO wins this one by a field goal, 14-11. Again, give them their due. Banks have our best intentions in mind with this. All the cards and accounts were created to target the needs of a specific client segment, like a tailored suit (Maybe a different analogy). All of our customer segments are somewhat unique, therefore they deserve unique products.

Again, give them their due. Banks have our best intentions in mind with this. All the cards and accounts were created to target the needs of a specific client segment, like a tailored suit (Maybe a different analogy). All of our customer segments are somewhat unique, therefore they deserve unique products.

Innovation gone astray

Let’s think about that customer segment really. It is still a heterogeneous group of customers, all with slightly different needs and wants, different incomes, debts, and even things like self-esteem and worth. With that targeted product, we are serving all of them reasonably well. Not perfectly, but they seem happy enough to stay. When their circumstances change, they can come in, fill out a bunch of forms, and we’ll give them a new card.

How many cards should a bank offer? How many accounts do they really need to offer? Let’s get really radical here and start with one. Just one. Call it a Smart Card, and it works for everyone. Your credit limit is based on your history and ability to pay. The colour of the card (standard, gold and platinum) is based on your credit limit. Your annual fee and interest rate are based on the colour of your card. Any cash back, rewards, etc. are based on your spending pattern. It’s all on the same card, and what happens with it depends on you individually, not the perceived needs of your segment as imagined by the bank. It is targeted at you and you only. How much better would the customer service representatives know the product? How much could we save on training, market research, brochures and leaflets? How much simpler could our web site be?

Do the same thing at the account level. We now offer one account – the Smart Account. Sure you can write cheques. We’ll pay interest based on the balance you hold. We’ll even eliminate the fees for students and seniors (those are my parents at the front of the line).

Again, the banks gasp. How will we differentiate ourselves? Well…how about on good old-fashioned service. Offer fewer products, but know them inside-out. Treat customers with dignity, respect, recognition, speed and efficiency – the last two are virtually impossible in a world of 9 credit cards and 13 accounts. When we simplify, we reduce complexity. Employees are consequently more knowledgeable. Staff and customer anxiety drops as people understand the system better.

Enter Lean

Rooted in all of this discussion is the concept of Lean. Lean is about value, or what the customer really wants. It may sound like I’m picking on the banks, but I’m not really. This is an exercise for all of us. How much anxiety and confusion are we creating for our customers with the myriad of services we offer? Think about the selection at the video store or the menu-board at Starbucks. Even something as simple as renting a movie at Blockbuster or buying a coffee-like beverage involves bad-decision risk. What if I don’t like this movie? I’ve wasted two hours and $6.00. This non-fat, caramel-flavoured Grande Latte was $5 and, you know what, I don’t really enjoy it. When customers look at our organizations, the decision risk is a hundred or a thousand times higher. In a bank, what does a customer really value? Most of us would say friendly, efficient service and knowledgeable staff.

A Bain and Company studyii recently indicated that most top-level executives believe their businesses are too complex. The result of this complexity is increased costs and hampered growth as “employees struggle to make sense of their service portfolio.” Each “product” their organization offers requires training, support, space, marketing, and work, and increases the complexity for front-line staff. Their customers feel the same way. Give us fewer choices, but really deliver on service and quality.

The difficulty lies in understanding how to approach the dialling out of some of that complexity. The most effective means of managing complexity is reduction: Simplify our offerings and focus on what customers really want. But, we really don’t appreciate the extent of the problem, so we have difficulty visualizing the opportunity. Any manager who assigns a team to eliminate the complexity in his department without setting the table properly first is just asking for trouble. Below, I recommend three steps that a department or organization should take before anyone goes anywhere near trying to trim a process or service line. The three steps are geared towards opening our eyes, and as the Lean folks say, ‘Learning to See’iii.

Moving to Lean: Three steps for managing – or eliminating – complexity

1. Shape Perception. Here, you are trying to help the team understand that everything we believe may not be as it seems. An easy way is to go to YouTube and type in “Awareness Test.” There is a list of tests, but the common theme is that viewers are asked to count the number of passes one of the team members makes with a basketball. Thirty seconds later, the audience normally agrees on how many passes they saw, but realize they missed the key message. Walking through the basketball players was a moon-walking bear or a gorilla doing Kung-Fu, and no one saw it. Aha!

2. Engage in a waste-elimination exercise: This is admittedly a silly, goofy task, so have some fun with it. Tell the team that the Oxford Dictionary called, and that because we are now a global society, it believes it’s time to eliminate some of the letters in the English alphabet – it’s too complex and difficult to learn. Oxford believes we can eliminate 3 to 5 letters, yet still be able to make all the same sounds we do now. Get started! The team will come up with F (replaced by ‘ph’), X (‘ks’), Q (‘kw’), and possibly C (‘k’ for a hard ‘c’, ‘s’ for a soft one), Z (‘s’), and perhaps more. On the white board, write a sentence with the revised alphabet. For example, “The kwik brown phoks gumps over the phense.” This gets really powerful when you insert a line from the company vision statement that focuses on customer value, and that is re-written on the board. “Our phokus is our kustomers.” It may be the first time people have really read it and truly thought about it.

3. Five “S” (Sort, Straighten, Shine, Standardize and Sustain). This is an old Lean tool, but a good one, because, like the first two, it hasn’t targeted a specific process yet. Unlike the first two, it starts to have a meaningful impact on your organization almost immediately. Picture again your garage. Put aside a few hours (or days), and sort everything into two piles – Keep and Chuck. The Keep pile is everything that belongs in the garage. Get rid of everything else, either to the dump or where it belongs. Straighten it up – put stuff where it belongs, maybe put up some shelves, cabinets as required. Shine the environment – this may take some new lighting or a coat of paint. Standardize – this is the way it belongs (train your kids), and sustain – keep it that way.

In the workplace, I like to pick some visible, high-traffic area. Take some photos before and after the exercise. People will be amazed at what you’ve done, and in a lot of cases, ask for your help in applying the Five “S” to their area.

The key thing here is that you have started to create some momentum and enthusiasm for a lean culture and environment without laying a glove on sacred products or services. At the same time, people are starting to understand that there may be some waste in the organization. Lean deals with that complexity and waste by focusing on what the customers want most, value. What does the customer want? In the end, that is a difficult, often moving target. What they don’t want, however, is 19 different credit cards.

Reprint from Ivey Business Journal

[© Reprinted and used by permission of the Ivey Business School]