A. Vellayan: As Long As There Is Growth, There’s No Problem

As chairman of one of India’s oldest conglomerates, the Murugappa group, A. Vellayan’s foremost challenge will be to accelerate expansion without diluting the group’s traditional philosophy and values

A. Vellayan (Murugappa group)

Age: 58

Profile: Chairman of Chennai-based Murugappa Group

India Rich List Rank: 55

Family wealth: $1.02 billion

Insights:

• Wants to stick to values such as integrity and trust

• But says decision making will have to be faster

Sometime in 1945, A.M.M. Vellayan, the second son of A.M. Murugappa Chettiar, went back to Burma to take stock of the wealth his family and his community left behind during the Japanese occupation. One evening, after a meeting, Vellayan walked back to his house. It was dark, there was no power. As he reached the door, a young man, who was waiting for him, pulled out a gun, shot him and sped away. Vellayan died immediately. He was 40.

Back in India, Murugappa Chettiar’s world crashed. He would spend the rest of his life in his family house at Pallathur, a village in southern Tamil Nadu, but not before taking two far-reaching decisions. First, he decided to pull out of all overseas investments — the family had holdings in Malaysia, Sri Lanka and Burma — and focus only on India. Second, he insisted that his eldest son, who had only daughters, adopt the second son of Vellayan. It was a wise decision, the youngest son A.M.M. Arunachalam told his biographer many years later: “It helped the family stay together.”

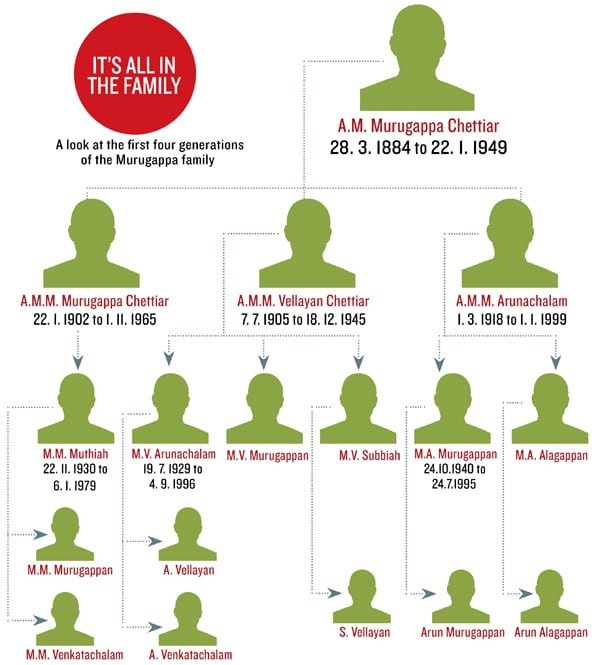

A. Vellayan, the grandson of the adventurous young man who lost his life in Burma, and the chairman of 110-year-old, $3.8-billion Murugappa Group since October 2009, knows that years down the line his own contribution will be judged by a similar metric — whether he managed to grow the business while keeping the family united.

The Goal

Vellayan, however, will get little encouragement from history.Across the world, the probability of a split in a family business rises with every passing generation. In India, Reliance split in the second generation and Bajaj in the third. Vellayan himself belongs to the fourth generation — one of the seven from that generation — and is overseeing the fifth coming on board.

What’s amazing about Murugappa is the way it built the business over many years, across generations, even while maintaining an united front, says K. Ramakrishnan, head of investment banking at Spark Capital, who has worked with the group for over 15 years. The group’s interests today span several sectors from abrasives and bicycles to fertilisers and financial services — across 29 companies employing over 32,000 people.

When Vellayan succeeded his uncle as chairman, it represented a significant change. For one, the mantle moved from the third to the fourth generation. More importantly, Vellayan is regarded as being more aggressive than the others. In 2003, he led one of biggest acquisitions of the group, when Coromandel Fertilisers, Murugappa’s flagship company, took over Godavari Fertilisers. It was hostile and Coromandel paid over 50 times the market price for each Godavari share. He also led the group’s entry into Russia and South Africa.

There are no overt signs of the leadership change at the group headquarters at Dare House, a British-built, 1930s building at Parry’s Corner near Chennai harbour. The photographs at the foyer are mostly of different CEOs with their teams, while those in the conference room are dominated by family elders.

But insiders talk of subtle changes. People are asked to think big and take risks. Access to the chairman has never been easier. “Earlier, the focus was on control. Now it’s about finding opportunities,” says V. Ravichandran, a director at Murugappa Corporate Board.

Vellayan, who went to the Warwick Business School for his masters and spent his entire career at Murugappa, says he will stick to values such as integrity and trust. “What will change is that decision making will have to be faster. We have to take some calculated risks even if we have only 75-80 percent data. We might miss an opportunity if we don’t move. Second, we have to look outside the country’s boundaries for opportunities if we want to grow fast. Third, there will be inorganic growth. We have people who are looking for deal flows rather than wait for them to come.”

Vellayan wants Murugappa’s growth to be three times faster than that of India’s GDP (gross domestic product). It’s not going to be easy. Part of the challenge lies in its portfolio. More than half its revenues come from agri-based businesses, a sector that grows slower than the GDP. And he has to achieve this while operating within the constraints of the group’s tradition of preferring profitability to revenue growth and of staying within its circle of competence.

The Boundaries

Some of the constraints were shaped by history. During the licence permit raj, Murugappa wasn’t good at the game. Of the 17 licences it applied for, it got only one. So, it focussed its energies on buying sick companies and turning them around. The MRTP (Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices) Act didn’t allow it to function as a single group, and it controlled its interests through cross holdings. Post liberalisation, it untangled these holdings, laid out systems for governance and the family’s role in it, and bought all companies under a single identity.

The restructuring turned out to be crucial as the following years saw a churn in the portfolio. It acquired Godavari Fertilisers in Andhra Pradesh, GMR Sugars in Karnataka, Sabero Organics in Gujarat, an abrasives plant in Russia, and the world’s largest manufacturer of zirconia in South Africa. It also sold its confectionaries business to Korea’s Lotte, sanitaryware business to Spain’s Rocco and most recently its mutual funds business to L&T Finance.

Yet, this churn belies the fact that the family has been mostly conservative, and exercised caution in getting into new businesses. Consider this: Before the founder’s son Vellayan made his fateful trip to Burma, one of the people he did business with was Azim Premji’s grandfather. Like Premji’s family, the Murugappas too started an IT hardware manufacturing business, but sold it off and lost out on one of the biggest growth stories.

Aversion to taking big risks and to step outside the comfort zone is only a part of the explanation. The other is a deep rooted desire to maintain the reputation of stability. “I think when it comes to Murugappa Group, the need to be seen as a trustworthy stable, company, will always override individual ambitions. And there’s nothing wrong in it,” says Arun Alagappan, a cousin of Vellayan who now works in Tube Investments (TI), which makes precision tubes, auto ancillaries and bicycles. “They are very particular about it,” says Ramakrishnan of Spark Capital. “And that has helped the group. Today, any banker worth his salt would give an arm and a leg to do business with them.”

They have hardly been immune to mishaps, but whenever that happens, they act fast, deploy their full strength and restore normalcy. What happened to Cholamandalam Investment and Finance is a case in point. In 2005, DBS of Singapore picked up 37.5 percent stake in Cholamandalam, and over the next few years expanded its personal credit portfolio by over Rs. 3,000 crore, a new area for the NBFC (non-banking financial company), which had dealt only in secured credit till then. The financial crisis struck and bad loans shot up, leaving a huge hole in its balance sheet.

M. Alagappan, the then chairman acted fast. He bought back the stake from DBS, and assigned N. Srinivasan, a finance whiz (and incidentally the elder brother of TCS CEO N. Chandrasekaran) in the corporate board to clear up the mess. Srinivasan took a series of steps — starting with putting a stop to consumer loans, selling off the mutual fund business, fixing the asset liability mismatch and getting back the bad loans.

In the process, around 2,000 people had to be laid off. It was around the time Jet Airways had fired its staff, and the ensuing protests had made headlines. “My chairman asked me if we will face a similar situation. I told him, ‘no’,” says Sridhar Ganesh, human resources director. The managers had gone out of their way to explain why they were doing what they were doing.

At the end of it, the company appointed Subbiah Vellayan, the son of former Murugappa chairman M.V. Subbiah, as new managing director of Cholamandalam. Subbiah Vellayan, a BTech from IIT Madras and MBA from University of Michigan, had spent six years working at McKinsey, Carlyle and 24/7 Customer, before joining the family business. He was heading LaserWords, the group’s BPO firm, when the family asked him to move to Cholamandalam.

Putting a family member in charge also sent the message that Murugappa was serious about its NBFC business.

The Code

The family plays an important role in career paths of the younger generation. In the 1980s, when Murugappas were planning to acquire an ailing EID Parry, M.V. Subbiah, who was then running TI, was opposed to the idea. The family elders not only went ahead with the buy, but also asked Subbiah to move to the new company. Subbiah obliged and eventually turned it around. M.M. Murugappan, a cousin of Vellayan, was more interested in scientific research and teaching but joined the family business after his father died. He too had stints at various positions in different group companies. “When I had an option, I chose. When I was requested, I went,” he says.

The idea of moving members across different businesses is not only to give them exposure, but also to ensure that the person isn’t too attached to one business, but takes the entire group into account.

Today, the group has a well-oiled system to bring the younger generation in. They have to first work in other organisations before getting into a group company. They work at various levels, gradually taking bigger responsibilities. They are also assigned a mentor.

Sridhar Ganesh, director-HR, says that the group is now expanding the scope of its mentorship programme to include business leaders from outside to mentor the next generation. In return for these privileges, the family member has to prove equal to an outside professional before claiming a promotion or bigger responsibility.

This system has worked. “I can only contrast it to what is happening in our own family,” says N. Murali, former managing director of The Hindu, who is fighting a legal battle with his brother and cousins. “In Murugappa Group, there is no sense of entitlement. You have to earn what you get.”

S. Gurumurthy, a chartered accountant who has seen a good number of disputes in business families and has also helped resolve many, says the Murugappas have put processes in place — in terms of a family council to take care of the family issues, and a very professional corporate board (it has only two family members in it) for business decisions. More importantly, you find the traditional values — respect for elders, respect for the community. “I believe all these played an important role in keeping the family united. It’s not that they have faced no problems, but they have found a way to solve them,” he says.

No one is sure if what worked in the past will work in the future. Vellayan, though, is betting on one big insurance policy. It’s called growth.

The Gameplan

Vellayan knows that a growth rate three times faster than the GDP will not come from the core business alone. His three big themes are adjacencies, backward integration and inorganic growth. “The core itself will only grow so much. Strategy will have to be to move away from core growth and to adjacencies,” Vellayan says. For example, in fertilisers it would mean a new segment like rural retail (Coromandel grew its retail operations to over 425 centres from two centres three years ago), or providing new services or products such as bionutrients, consulting or farm mechanisation.

In fertilisers again, its efforts at backward integration took it to South Africa. It entered the country through Foskor, which makes phosphoric acid, a key raw material for fertilisers. “We kind of followed the L.N. Mittal model in South Africa. We went in to turn around the operations in return for sweat equity. It was tough environment and there were doubts and even hostility,” says Vellayan. Eventually, the turnaround happened, and Coromandel secured the supply of key raw materials.

In sugar, Vellayan is betting on the sector being deregulated eventually. “When that happens, the manufacturers will have a good play,” he says.

The strategy here is twofold: First, to expand the capacities of each of its existing mills, and second, to look out for weaker players.

When the market is down it’s tough for the smaller players to survive, and the price tends to be good. Last year, the group acquired majority stake in GMR Industries and a year earlier in Sadhashiv Sugars, both based in Karnataka. The idea is that the core sector might see slow growth, but Murugappa will grow faster through new markets and gaining market share.

In TI, its engineering business, a majority of the investments would go into building tubes capacity. Again, here, the bicycle market is shrinking but TI has been working hard at rebranding it as a lifestyle product. (Around the time Nano launched, TI Cycles introduced a Rs. 2 lakh bicycle).

In financial services, the focus is now on building back the asset-based business. “There is a long way to go. But, there is a lot of space in the market to grow 20-25 percent every year,” Vellayan says.

Growth is a recurring theme with almost everyone Forbes India spoke to. And that has a special significance for managing family expectations as well.

“The approach we have is that of building value in terms of market cap. Those family members who can add value will be in management. Those who can’t will anyway get the benefit from the returns by virtue of being shareholders. At the end of the day what do you want? Do you want to be suboptimal in managing and get a lower return, or get a higher return under a professional management?” asks A. Vellayan.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)