Arun Maira: Mistrust Of Capitalism

With the voices of protest increasing against corporations, it’s about time businesses redefine their relationship with society and formulate new rules for corporate conduct

There comes a tide in the affairs of men,” Shakespeare cautioned. Tsunami warnings are now ringing about the global economy. The global financial system is under stress. Economic growth is stumbling. Confidence in governments is decreasing everywhere. Multilateral institutions like the WTO (World Trade Organization) and IMF (International Monetary Fund), created to promote global integration and stability, are ineffective. Communism was declared dead with the fall of the Berlin Wall. Now, there is less faith in the concept of the free market, even amongst Western economists. Why has liberal, free market capitalism, the victor of the Cold War of ideologies, also stumbled?

The confluence of three mega trends has increased mistrust in capitalist institutions. The first is the triumphal and arrogant advance of liberal capitalist ideas of economic management led by the US, which grew after the ideological opposition to them collapsed 20 years ago with the unravelling of socialist regimes behind the Iron Curtain.

The Indian economy’s boat also rose with this tide when government controls on industry were dismantled in 1991. With this advance of capitalism, CEOs of multinational companies became the chiefs of the world, whose court assembled in Davos in January each year, and to which heads of government flocked for attention. Thomas Friedman described this mega trend as the flattening of the world by the spread of global finance, global corporations, global brands and global ideas (mostly American), aided by the Internet.

The explosion of access to information through the Internet and social media, proliferation of mobile phones, and 24x7 news media, is the second mega trend. Like a rising tide that cares not whose boat it lifts, technology enables all ideas to spread. Not only the advertisements of global brands, but also voices of protest against them. Not only do 21st century communication technologies enable security forces to snoop, they also equip terrorists to co-ordinate, and non-violent protestors to organise. The Jasmine Revolutions in Arab countries and Anna Hazare’s campaign against corruption in India were accelerated by ubiquitous communication technologies.

The third mega trend is the deepening recognition of human rights: The equal rights of women and men, of all races, and of all people whether rich or poor. The concept of rights is expanding too: From political rights to vote, to social rights for respect and equal treatment, and onto fundamental rights to education, health, and equal opportunity, which people are charging their governments to ensure. The concern for human rights, which grew larger in the latter half of the 20th century, has expanded and become deeper in the opening decade of the 21st century with the proliferation of civil society advocacy groups enabled by the reach of communication technologies.

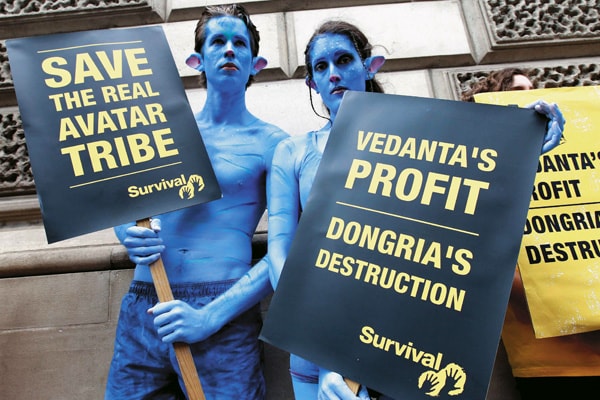

Image: Stefan Wermuth_Reuters

FIGHT FOR RIGHT Demonstrators, including a pair dressed as characters from the film Avatar, protest Vedanta Resources’ mining activities in Orissa during the company’s AGM in London

Like the beleaguered boat in Sebastian Junger’s The Perfect Storm, that sailed into an unprecedented confluence of three storm systems in the North Atlantic, the coming together with great force of these three mega trends is putting to test the institutions, i.e. the ships and navigation systems of capitalism that were not designed for such conditions.

A principal institution of capitalism is the limited liability corporation, a vehicle that has enabled investors to increase their wealth and has also enabled ideas to be turned into products and services for people. However, the damage caused by the activities of some corporations to the environment and lives of people in many parts of the world, and the conduct of highly paid CEOs and corporate boards in the global financial crisis, has damaged public trust in corporations and their leaders.

There is public demand for more regulation of corporations and public resistance to giving them permissions for expansion of their operations, as in the tribal areas of India, unless they behave more responsibly.

The only consolation for corporations who fear government regulation is that the public trusts governments even less than corporations! In fact, surveys reveal that people trust civil society organisations more than both corporations and governments.

Corporations fear civil society, with its diversity of interests, even more than they dislike governments, because it is more difficult for corporations to make contracts with civil society with its myriad organisations and no designated overlord. For the same reason, governments too have a difficult relationship with civil society. At the same time, civil society mistrusts both governments and business corporations. Mistrust all around!

The breakdown of trust is the root cause of the uncertainty about the global economy. Investors nervously watch the gyrations and downward slide in stock markets and economic indicators. Stock market analysts explain that market ‘sentiments’ are not good.

Economists worry that growth is not picking up. They say that consumer (and investor) ‘confidence’ must be restored. People are losing confidence in institutions and their leaders. Until trust is built, sentiments improved, and confidence restored, good times will not come. Therefore, we must understand the following:

- What are the conditions for trust within society?

- How can trust be proactively built?

- With the mega trends shaping the world at this time, what would be the steps that business leaders may take to rebuild trust in business?

Rules We Choose to Live By

Trust and ethical principles are fundamental forces shaping systems of interacting agents. The processes by which ethical principles are learned and applied by agents, and by which trust is developed amongst them are complex. Trust is present even in ant communities. Biologists observe that every ant, diligently going about its own business, intuitively expects other ants to perform their roles. Thus, by mutual inter-dependence the entire community is able to improve its condition. There is some form of ethics guiding the ants’ behaviours. However, ants, and other communities of living beings other than humans, do not consciously change, or even wish to change (as far as we know) the rules that drive the behaviour of individuals. Whereas, humans do, and this may be the principal distinction between human and other societies. Therefore, humans become curious about how ethical principles are learned and applied, and how they can be changed. And also about how the level of trust within society can be deliberately improved.

The critical difference is deliberate intent to change. Human societies, like all others, are always operating by some rules. The rules can be written rules as well as unwritten rules. The application of those rules enables society to function as it is. Therefore, any attempt to change the rules for the sake of improving them risks damaging the ability of society to function as well as it is, should the new rules prove less effective. At its heart, this is the fundamental concern of the ‘leave it to the market’ purists. They fear that any attempt by government or others to externally impose rules will damage the economy’s ability to improve itself.

Nevertheless, as the poet Robert Frost says, there come times when human aspirations for something better come to the fore and we do not want to leave our future to forces beyond us because,

Ah, when to the heart of man

Was it ever less than a treason

To go with the drift of things,

To yield with a grace to reason,

And bow and accept the end

Of a love or a season?

There are times when many in the world wish to change the rules by which their society operates. We are at one such moment.

Frost points to the contention between reason and aspiration. When market economists talk about ‘rational’ self interest, they presume there are rational reasons for which free agents do what they do. Which raises questions: What is the nature of this rationality? How are ‘rational’ rules learned? And raises yet another question: Do all free agents follow the same rules or may they be following different rules? If we have to trust each other, we must, at the very least, know the rules that guide others, even if we do not follow the same rules ourselves. We need to know so that we can predict others’ behaviours, thus ‘trusting’ them to do what we expect they will, even if it hurts us.

Of course, the quality of trust we really want in our society for it to be a harmonious society is not only that we should know the rules by which others operate, we must trust they follow the same unwritten rules we do and have no intention to harm us.

I make this introduction to point to the solutions we need if we wish to strengthen/improve the condition of ethics and trust in society and business. The solutions lie in the realm of processes whereby societal norms and rules are consciously, collectively, and voluntarily framed. I highlight the ‘voluntary’ quality of the process. Good rules must apply to all for the harmonious condition of trust mentioned before.

However, democrats (and free marketers) like myself would insist that it is preferable that agents adopt these rules in their own self-interest, and that rules unacceptable to them should not be harshly imposed on them by a hierarchical power over them.

Institutional Solutions: The Missing Middles

The challenge before business leaders now is to build public trust in business institutions. I present a model of the eco-system of the relevant institutions and processes to propose two steps business leaders can take to rebuild trust in business.

Three principal sets of institutions perform in the theatre of business relationships with society: Business institutions, government institutions and a broad set of civil society institutions (which includes political parties, labour unions, and myriad civil society organisations representing various stakeholders and their concerns).

The re-formulation of the contract between business and society requires a dialogue between these principal actors. The debate is already taking place in the media, in seminars, in coffee shops, on the Internet, social media and other forums. Societal norms and institutions are generally shaped by such ‘conversations’ that take place across space and time. With these conversations, new ideas emerge that guide the conduct of societal actors. Some of these ideas cause new laws to be written. Many ideas become new ‘unwritten rules’ about the ‘way in which things are done around here’.

Solution 1 is a more systematic process with the deliberate intent to redefine the contract of business and society and develop new rules of the game for corporate conduct.

All principal stakeholders must be engaged in the process. The process should be conducted according to the best principles for consensus-building and with the best available tools for stakeholder dialogue. The dialogue has to be conducted at many levels and in many places, and around various issues. Therefore, the principles and tools for good dialogue amongst stakeholders whose perceptions and ideologies may differ must become widespread protocols. Just as protocols for safe driving and protocols for accessing the Internet have become widespread and routine, the need for stakeholders to resolve the contract of business with society in multiple settings, requires a widespread capability for developing new rules collaboratively.

Solution 2 is to strengthen business associations that can develop and impose rules of conduct on their own members.

Corporations are wary of regulation by government bureaucracy. They complain that too much government interference dampens the energy of business. At the same time, society is unwilling to trust business corporations to behave responsibly: The ‘animal spirit’ can get out of hand. Those who fear government interference admit that internal corporate governance processes must be strengthened, and the ethics of CEOs and board members improved, so that corporations should require very little external regulation. Such efforts have begun and must continue.

However, they have not produced satisfactory results so far. Corporate scams have persisted, sometimes arising even within corporations celebrated for their good corporate governance! External oversight of corporate behaviour seems to be required until corporations and their managers become truly ethical and trustworthy.

Rather than leave this oversight to government alone, a third structure, supplementing internal control and state regulatory processes, should be created so that government oversight structures could be less thick and heavy. This third structure, which could take some of the oversight load, could be stronger associations. Such associations should provide their members a process for debating and agreeing on voluntarily imposed norms and assistance to members to develop capabilities to conform to these norms and, for such associations to be trusted as effective institutions for self-governance, internal governance that disciplines errant members.

Many institutions are involved in the evolution and dissemination of ideas affecting the conduct of business in society. They include schools of business, economics and law. The media also has a very powerful role, not the least through the ‘role models’ it projects and the ‘values’ these models represent. These institutions provide the third layer of the eco-system of business and society. Within them too, change is necessary in response to the need felt for improvement in ethics and trust in business.

Business schools, management consultancies and the media have influence on the propagation of ‘values’ that guide the behaviour of business managers. Their insights are based on observations of the performance of business actors. In other words, for their ideas to change, perhaps actual behaviours of actors must change first. Therefore, the process by which actors change their own behaviours is a key to changing the ideas that permeate the business-society eco-system. Hence, the two solutions proposed here are at the heart of the process by which the system can create new ideas to guide itself.

Finally, to the Heart of Leadership

A leader is she or he who takes the first steps towards what she or he deeply cares about, in ways that others will follow. What do business leaders really care about beyond shareholder value? Will they take the first steps to fill the ‘missing middles’ in the business-society ecosystem by which society can reshape the contracts between its institutions and define new rules of the game? Will they take steps to create platforms and processes for an open-hearted and open-minded dialogue with others who may not be trustful of them?

Arun Maira is a member of the Planning Commission chaired by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. In this ministerial level position, he is responsible for shaping policies and programmes around industrialisation, urbanisation and tourism. Prior to this assignment, he was chairman of the Boston Consulting Group in India. He has also served on the boards of several large Indian conglomerates like Tata, Birla, Godrej, Hero and Mahindra. Maira is the author of several books that include Shaping the Future, Remaking India and Transforming Capitalism.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)