Tulsi Tanti: Reviving Suzlon

The global financial crisis almost wrecked Suzlon. But the company’s chairman and managing director, Tulsi Tanti, held his nerve and changed strategies. And now, he’s dreaming big again

Tulsi Tanti

Age: 53

Profile: Chairman & managing director, Suzlon

Rich List Rank: 74 (ranked 8th in 2005, and 10th in 2007)

Wealth: $690 million

Turnaround Tale:

•Has questioned every key business assumption, virtually torn down every element of strategy and rebuilt a whole new business.

By the end of this year, Suzlon will become the most profitable wind energy company in the world.” Sitting in his new second floor office at One Earth, the impressive new campus he’s built for Rs. 430 crore on the outskirts of Pune, Tulsi Tanti sounds unusually composed and confident for a man who’s emerged from a near-death experience in the past 36 months.

Apparently, for him, it’s now no longer a question of survival. “I am not concerned about this or the next quarter. Today, 70 percent of my focus is on building the organisation for the long-term opportunity,” he says.

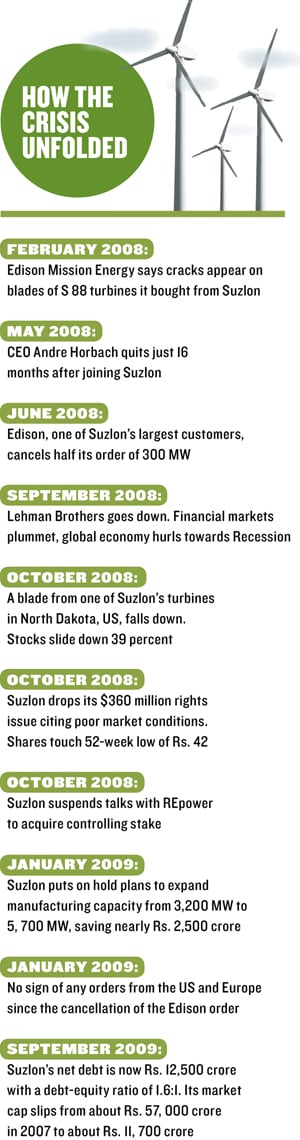

Ever since September 2008, when the financial crisis struck, Tanti had faced an uphill struggle to even stay afloat. He was grappling with a product recall crisis, an over-leveraged balance sheet, a messy acquisition of German wind energy major REpower Systems, a spate of senior level exits and, as credit markets froze, the market for wind turbines all but dried up.

Till then, Tanti had come to be regarded as one of the poster-boys of India Inc’s globalisation story. His was a story of entrepreneurship and unbridled ambition as Suzlon became the fastest growing wind energy company in the world, selling wind turbines to nearly 25 countries, across the US, Europe, Latin America and Asia. In 2005, when Tanti entered the Forbes list of the 40 richest Indians, not many had even noticed him. By 2007, he had created a business that was valued at Rs. 57,000 crore in less than 13 years.

Late last week, Suzlon’s second quarter results provided the first signs of a company on the mend. Suzlon reported revenues of Rs. 9,397 crore for the first six months of the 2011-2012 financial year, up 52 percent from last year. It also reported a profit of Rs. 108 crore, against a loss of Rs. 1,281 crore for the first six months of the same fiscal. But, at Rs. 11,100 crore, Tanti’s net debts are still substantial. However, Suzlon’s debt-equity ratio, which had ballooned to 2:1 at the height of the crisis, now stands at a more manageable 1.7:1.

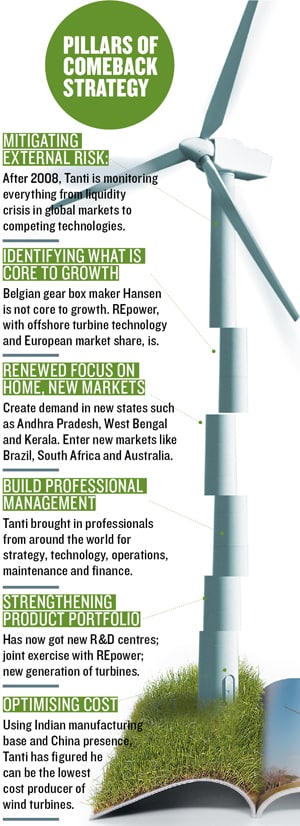

But the numbers don’t quite tell the full story of Suzlon’s revival. During this 36-month period, Tanti has hunkered down, questioned every key business assumption, virtually torn down every element of his strategy and rebuilt a whole new business.

Take, for instance, the cost of wind energy itself. Suzlon was always one of the lowest cost producers of wind turbines in the world after the Chinese. In the past 18 months, Tanti has used the crisis to restructure the business even further. Around 2007-08, the cost of one unit of power from wind energy cost Rs. 5, compared to Rs. 2 to Rs. 2.75 for coal. Today, the cost of wind power has come down to between Rs. 3.25 and Rs. 3.5, while the price of power from coal has increased to Rs. 3 to Rs. 3.10.

Today, as the wind energy market begins to reboot — 36 gigawatt of new capacity was added last year, nearly half of it coming from the emerging markets of Brazil, Africa, China and India — Suzlon has once more emerged as one of the fastest growing wind energy players, and the most profitable as well (gross margins of 35 percent).

In a Lurch

But, in 2008, when disaster struck, Suzlon was completely caught on the wrong foot. “In September 2008, when Lehman Brothers collapsed, our sales team could not believe that the market was not there,” says Robin Banerjee, chief financial officer at Suzlon. The company still believed that it was a temporary situation and orders would come. Most of them were used to a situation where demand for wind turbines far out-stripped its supply.

“But December came and there were still no orders, and then there was nothing in January or February either. By March 2009, we realised it was going to be a long term,” adds Banerjee. For Tanti, this was a period for deep introspection.

“For about six months, Mr. Tanti questioned all the assumptions on which he had built the business. He wanted to understand why Suzlon was in the middle of such a big crisis,” says Sumant Sinha, former COO of Suzlon and now managing director of ReNew Power, an independent power producer. Tanti went back to the drawing board. After the go-go years, he realised it was time to consolidate operations. The crisis provided the perfect opportunity. “If I am in a growth situation, then I cannot consolidate my organisation, and for the past decade we had just been growing. So, now I had the chance to build the organisation for the next 10 years. Because a lot of change is needed, like product, organisational structure, management bandwidth and resource planning,” says Tanti.

As 2008 came to a close, there were no new orders from Europe or the US, the two biggest wind energy markets of the world. These had been the mainstays of Suzlon’s growth, where the company received big ticket orders from large power utilities. The financial meltdown scuttled new orders as large wind farms needed a lot of investment. It didn’t help that Suzlon’s reputation had taken a major hit earlier that year because of blade failures.

Around March 2009, Tanti realised that the company will need to focus somewhere else. “There is no rocket science here. When you find that you can’t sell either in the US or Europe, then what do you do? You look for just about any other place where you can sell,” says Banerjee.

It meant taking a quick call to shut down capacity in markets where growth has all but petered out. Suzlon had a 600-strong workforce at its blade making factory in Pipestone, Minnesota, which it shut down in phases.

For Tanti, it also meant falling back on the Indian market. India was the only country slightly insulated from the global meltdown. Suzlon, the market leader, decided that a good way to go about it would be to expand the market.

“Here we have increased the size of our business and unlocked value,” says Tanti. This year, the Indian market will do about 3,000 MW, up from 2,200 MW last year. And that is likely to go up to 4,000 MW next year.

However simple this may sound, this didn’t happen overnight. Instead of battling rivals like Vestas and Enercon in the more established markets of Maharashtra, Gujarat or Tamil Nadu, Suzlon’s research and sales teams ventured out to new states like Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Kerala.

Most of these are low to moderate wind power markets. And, unlike other multinational companies that focussed on merely selling turbines, Suzlon had a complete turnkey solution approach. It involved studying the wind potential, acquiring land, setting up financing and post-sale services and then selling the whole proposition to an interested customer. That helped significantly ease the process and create more value for the customer.

“Three years ago, I did not put up a single turbine for Madhya Pradesh because it was not a priority for me. At that time, opening up another country was my priority,” says Tanti. Most of the new orders in the past 36 months have come from public sector units like GAIL, NALCO, Gujarat State Fertilizers & Chemicals and Independent Power Producers (IPP) like Caparo Energy.

To begin with, Suzlon didn’t have the requisite product to serve these new markets in India. Medium and low wind sites need a different turbine; a larger rotor area to improve efficiency.

So, Tanti fast-tracked the new generation of turbines, 9X, for medium and low wind sites. The commercial production of these turbines began earlier this year.

The same Indian strategy was then extended to other emerging countries like Brazil, South Africa, Sri Lanka and Australia, just when these markets were about to take off.

For instance, Suzlon had entered the Brazilian market way back in 2007. As things stand today, Suzlon is the second largest wind turbine manufacturing company in Brazil by market share.

Arthur Lavierie, CEO of Suzlon Brazil, who Tanti hired from a leading power utility firm Seves Brazil in 2009, says it took Brazil about a decade to get to an installed wind energy capacity of 1,000 MW. “We have now 6,000 MW of projects auctioned by the government and those projects need to be deployed by the end of 2014. So that’s an accelerated growth,” he says. To further optimise costs, Suzlon is setting up a blade manufacturing facility in Brazil by investing about $30 million.

Creating land banks, ahead of demand, is now an integral part of Tanti’s strategy. “Today, these sites are going at a throwaway price. But once the demand comes in, we will have to pay 10 times [the cost],” says Tanti. The results are trickling in. In the past 36 months, Suzlon has bagged orders of more than 150 MW in Australia, 218 MW in Brazil, 31 MW in Sri Lanka and 159 MW in South Africa, making it one of the most formidable players in emerging markets.

The key to a strong emerging market strategy has also been Tanti’s new staffing plan. Till the crisis struck in 2008, Tanti had hoped that a senior executive from a blue-chip company would be a great fit to lead his global surge. He picked Andre Horbach, who headed GE’s commercial and industrial business in the US, as Suzlon’s CEO. Horbach was soon out of depth in the strongly entrepreneurial environment at Suzlon and was unable to manage the breakneck speed at which the company was growing.

Tanti then decided to rely on strong local teams in every market that he entered and gave them autonomy. “I have not transferred any Indian manager to any of the 32 countries in which we operate. We didn’t want to have a centralised management, so that these people can drive the business with full ownership and loyalty,” he says.

And a lot of this can be credited to Frans Visscher, the chief human resources officer at Suzlon. Before Visscher joined Suzlon two years ago, he was the managing director at Korn/Ferry International, one of the largest executive search firms in the world. Visscher has been a close advisor to Tanti for several years now and has done almost all the major talent scouting for the company. “On the organisational processes and people side, I think we have a good team in place now not only at the country, but also at the corporate level,” says Visscher.

But none of these efforts would have yielded results without squaring up to an important and immediate problem. Suzlon had borrowed extensively. By December 2008, Tanti realised he needed money to pay back the debt.

Applying the Salve

To begin with, Suzlon refinanced its debt. At the time, Suzlon’s debt was split between those borrowed from Indian and foreign banks. The foreign debt was about Rs. 2,000 crore. This debt has less interest obligation, but very strict repayment obligations. Indian debt on the other hand has repayment obligations, but is not that strict. “So the question was how to mitigate the financial risk. Otherwise, we should not lose the smart acquisitions we made like REpower,” says Tanti.

Around March 2009, Suzlon figured that its next foreign loan repayment was scheduled for September that year. To avoid the pressure, Suzlon approached several Indian banks. This foreign currency debt had been lent by the foreign lenders against REpower’s shares.

REpower is worth about Rs. 10,000 crore, but debt was only Rs. 2,000 crore. “We went to our Indian lenders and asked them to lend us in Indian rupees so that I can pay off these foreign lenders in exchange for REpower shares. It was a very good situation for the Indian bankers because they got five times cover,” says Banerjee.

In return, Suzlon got a two-year moratorium and a three years’ repayment period, which has served as a cushion.

With the foreign debt taken care of, Tanti took a closer look at his backward integration strategy. That meant focussing on assembly and developing component vendors to take care of timely supplies. Younger brother Girish was given the task of building a new supply chain, across China and India. Twenty percent of all components today are sourced from China. That helped reduce the capital employed in the business and brought down the break-even level.

It also meant Hansen, the Belgium-based gear box manufacturing company Suzlon had acquired, had to go. In 2006, when the wind energy business was on a high, Tanti had bought Hansen to de-bottleneck an input shortage problem.

But now with Hansen’s expansion in China and India, Suzlon worked out a long standing contract with the company. Earlier this month, Suzlon divested its complete stake in Hansen; a move which has fetched the company Rs. 4,000 crore over the past 24 months.

By the end of this year, Suzlon hopes to complete its REpower acquisition by buying out the remaining minority shareholders. This will mark another important turning point in Tanti’s revival strategy. REpower is among the largest offshore wind turbine makers in the world. In markets like Europe, where there is no more scope for onshore development, REpower will provide the perfect fit for Suzlon.

As my editor and I prepare to leave his office, Tanti hurriedly pulls out a presentation on his iPad. Code-named Project London, it is a detailed step-by-step operational integration of Suzlon and REpower. It has minute details of how manufacturing synergies will be tapped and sketches out clear roles and responsibilities of both companies. The elaborate planning drills are indication that Tanti isn’t leaving anything to chance, ever again.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)