Indian automobile startups: Ahead of the EV game

How startups are turning out to be the torchbearers of the big Indian electric vehicle revolution

Jeetender Sharma, founder and MD, Okinawa Autotech, says since January 2017, the company has sold 5,000 units of Ridge, its first e-scooter

Jeetender Sharma, founder and MD, Okinawa Autotech, says since January 2017, the company has sold 5,000 units of Ridge, its first e-scooter

Image: Amit Verma

In 2010, when Raja Gayam was converting his father’s bus body building unit in Hyderabad into an autorickshaw manufacturing plant, he also decided to set up Gayam Motor Works (GMW) to manufacture electric autorickshaws. His brother Rahul, who joined him in 2013, was then working in the clean energy space in the US. They wanted to accelerate the world’s transition towards smart and sustainable mobility.

This was way before the Indian government announced its policy to incentivise electric vehicle (EV) buyers in 2015 and Vision 2030—its plan to turn India 100 percent electric by that year. The Gayam brothers sensed a huge market in India, the world’s third largest three-wheeler producer and exporter, and set out to create a product and service that would overcome the vast limitations of the EV ecosystem: Lack of charging infrastructure, long charging time, limited battery range and unreliable power grids.

“Gayam Motor Works is the manufacturer of India’s first electric three-wheelers powered by lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries with a swapping system (Pune-based Kinetic Green Energy and Power Solutions Limited launched its e-rickshaws, Kinetic Safar, with Li-ion batteries only last year) and an e-cycle called LIMITLESS,” says Sri Harsha Bavirisetty, chief operations officer at GMW. Using imported Li-ion batteries, it has developed proprietary Li-ion battery technology and intelligent Battery Management Systems (BMS) for e-mobility and charging points, he adds. Eight years on, the company exports its e-autorickshaws and e-cycles to 15 countries, including the US and markets in Africa, Asia, Central America, and Europe, apart from selling them at home.

The firm primarily caters to the last-mile connectivity segment. For its e-autos, it has clients like BigBasket, Amazon India, and Flipkart’s logistics arm e-kart (pilot phase in Hyderabad), while for its e-cycles, it has clients like UberEats in Singapore, Hong Kong, and San Francisco, as well as Swiggy (pilot phase in Bengaluru) in India.

“Charging batteries at stations and swapping batteries within minutes rather than waiting for them to charge for hours sounds like a great way to defeat range anxiety. In two to three minutes, a driver can drop off his discharged battery and have a 110 km range to get back on the road,” says Bavirisetty, adding that since they service B2B logistics, they use company warehouses, where the vehicles are loaded and unloaded, as charging points and battery swapping bunkers.

GMW—where Raja, with his automobile manufacturing expertise, is CEO and Rahul, with his technical background in EVs, is CTO—is now planning to build infrastructure for the retail market after a $15 million Series A funding round. It is also planning to get into bike-sharing at resorts, resident areas, ports areas and IT parks and is in talks with Microsoft, Adani and Art of Living. The Asian Development Bank is also doing a technical evaluation with them to set up a battery-swapping mechanism in Afghanistan.

Whether it’s ecommerce, fintech, ride-hailing or food delivery, the largest disruptions in the last decade in the Indian market have been driven by startups. The same seems to be the case with the automobile industry.

Even as most legacy carmakers—barring Mahindra—are busy chalking out their EV plans, several Indian startups are taking the lead in creating an EV ecosystem in the country.

“In every industry, traditional players have vested interests in maintaining status quo. They have invested billions of dollars over several decades in research and development (R&D). It’s difficult to just give up on the fossil fuel legacy and diversify assets, plans and production into a nascent space,” says Sanjay Puri, founder, AutoNebula, a Pune-based connected mobility accelerator. It is this latency that provides startups the headspace to dive into a new market. “Many innovative leaders are leaving their companies to start their own ventures in the EV space—a trend that a US-based [then] startup Tesla made mainstream,” he adds.

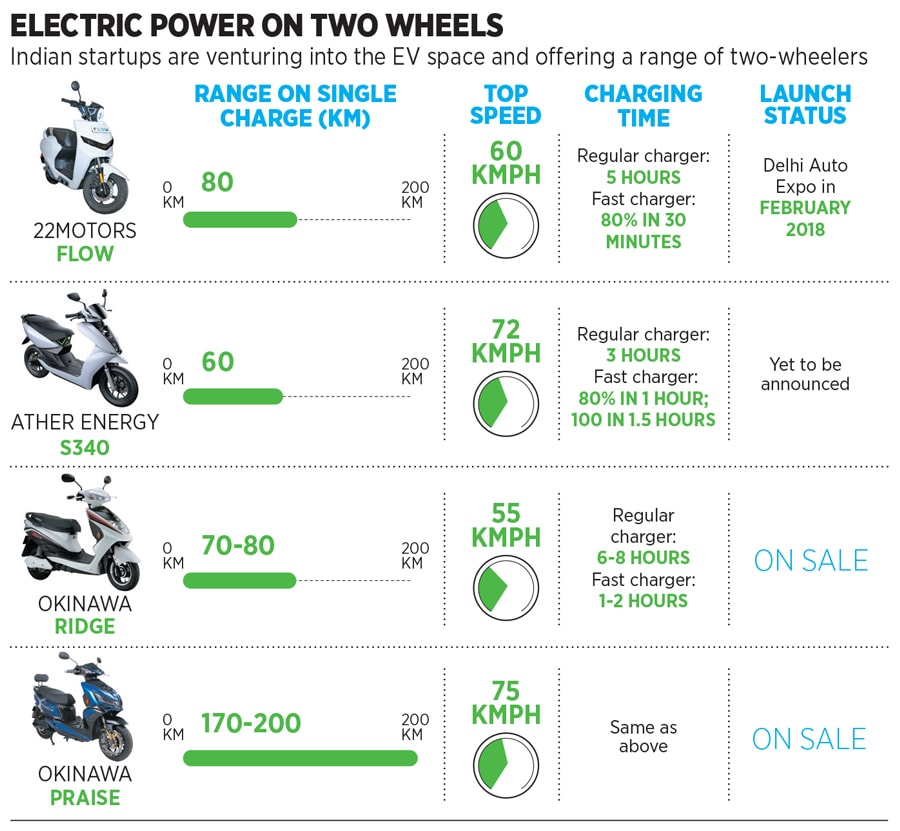

Take Gurugram-based Okinawa Autotech, for instance, which started in 2015 with the aim of offering an EV that combined power, range, safety and environmental sustainability. Since its launch in January 2017, Okinawa has sold 5,000 units of the Ridge, its first e-scooter. In December last year, the Ridge was followed by the longer-range and higher-top speed Praise. “We have received 2,000 bookings so far and expect to sell 25,000 units in 2018,” says Jeetender Sharma, founder and managing director, Okinawa. The scooter is powered by valve-regulated lead acid batteries, and the Praise will get a Li-ion battery option soon.

Okinawa has a manufacturing facility in Bhiwadi, Rajasthan, which churns out 300 units per shift, making 600 units in a day. The 40,000 sq ft facility was started with an investment of ₹30 crore and has an annual capacity of 1.8 lakh units. “We plan to invest ₹250 crore over two years in the plant and manufacturing processes, R&D, new product development and sales and marketing for dealer expansion,” says Sharma. Okinawa will also soon set up a second plant to introduce “a variety of vehicles”.

Smartphones on wheels

Gurugram-based 22Motors and Bengaluru-based Ather Energy are not stopping at an e-scooter but going further—they are in the race to launch India’s first smart scooter. Li-ion batteries, SIM card, Google Maps, GSM, touchscreen, apps, notifications, smart features, Artificial Intelligence, user profiles, security features—the features of the electric scooters in development by these two homegrown startups sound less like vehicles and more like smartphones. Both the e-scooters will use data collected from multiple sensors on nearly each part of the connected vehicle to learn about the rider’s riding technique and allow the owners to customise their vehicles.

“EVs lend themselves to offer use cases in intelligent connected mobility. With all the data from the vehicles, data scientists can help customise the e-scooter and every ride for the rider,” says Tarun Mehta, co-founder and CEO, Ather Energy. The company was set up by IIT-Madras alumni Mehta and Swapnil Jain, co-founder and CTO, in 2013, and they have been perfecting their smart and connected S340 for the last four years. “Matching the performance of existing petrol scooters was our primary focus; we can’t rely on altruism alone for sales,” says Mehta. The S340 will be connected to the cloud and “will keep learning and improving with usage”, he adds.

Ather plans to set up an assembly line in Bengaluru to make its own battery packs that will cater to the needs of its vehicle perfectly. “We built the first one three years ago. We finally feel good about its performance and quality,” says Mehta. The S340 is currently running production rounds though a launch date announcement is still some time away.

Parveen Kharb, co-founder and CEO, and Farhaan Shabbir, co-founder and president, 22Motors, say they set up the firm in 2016 as a technology company and not just a vehicle manufacturer, to develop electric mobility for the 22nd century. “We don’t want to reinvent the wheel by making plastics and metal. A scooter has to go from point A to B; doing that smartly is our job,” says Kharb. The connected, smart e-scooter FLOW will launch at the Delhi Auto Expo this month at an estimated price of ₹65,000-70,000 (ex-showroom price) and deliveries are expected to start in May-June. At a price point only slightly higher than the petrol-fuel two-wheeler market leader Honda Activa despite the expensive Li-ion battery, and several smart features like geofencing, cruise control, and drag mode, which enables the scooter to ‘walk’ alongside the rider, reverse and connected mobility, it is likely to turn heads.

“Making our own battery packs helped us reduce the cost by about 30-35 percent,” Kharb says. Its factory in Bhiwadi will initially make 200 scooters per day, increasing it to 300 a day. The company aims to manufacture 2 lakh EVs in three years. 22Motors will also add an assembly line for its battery packs at the unit. Kharb boasts of their unique wireless battery packs that use the ‘pack well’ technology, i.e. ultra-thin strips to transmit current that can detect a problem before a part malfunctions.

People Movers

Startups like Uber and Ola are also riding the EV wave. Ola took the plunge in 2017 by launching a multimodal EV initiative in Nagpur, Maharashtra, with an investment of ₹50 crore, an Ola spokesperson tells Forbes India. In November 2017, Uber announced a partnership with Mahindra “to provide hundreds of EVs in New Delhi and Hyderabad in the pilot phase; to be later extended to other cities”, Uber India had said in a statement. Zoomcar too has plans to add 12,500 EVs to its fleet in two years.

Bengaluru-based Lithium Urban Technologies, India’s first all-EV fleet for corporates, set up by Sanjay Krishnan, CEO, and ex-Nasa scientist Ashwin Mahesh, in 2015, has over 400 e-vehicles in its fleet. They plan to expand this to 10,000 vehicles in the next 36 months. “We see ourselves at the intersection of battery and vehicle technology, urban and energy infrastructure and fleet management,” says Krishnan, adding, “We sell productivity based on data analytics.” It provides fleet services to Accenture, Tesco, VMware, Adobe Systems Inc and Epsilon.

Ola’s electric fleet in Nagpur has 200 vehicles, including Mahindra e20s and Veritos, and cars from OEMs like Tata Motors, Kinetic, TVS and China’s BYD Auto. It also has e-rickshaws. Indian Oil Corporation and Ola set up a charging station in the city, while Hindustan Petrochemicals Company has also ventured into setting up charging infrastructure in the city.

The centre and states must motivate startups to stay the course for the long haul

Mahindra’s EVs on the Uber platform will include the e2oPlus hatch and the eVerito sedan. “We aim to build a more sustainable future of mobility by moving more people needing on-demand services with fewer, fuller, and more efficient vehicle trips,” says Madhu Kannan, chief business officer, Uber India & Emerging Markets. Mahindra and Uber India will also work closely with public and private players to set up common use charging ecosystems at multiple locations in the cities.

Serial entrepreneur Bhupendra Kumar Modi-led Singapore Electric Vehicles (SEV) has an extensive plan to enter the EV space in India. “We plan to set up an EV manufacturing unit, charging infrastructure and maybe even a fleet management system in India,” says Maneesh Tripathi, executive director and Group CEO, Si2i Ltd, of which SEV is a subsidiary.

The plant will be set up in ModiCiti, near Rampur in Uttar Pradesh (UP), which is owned by Modi’s Smart Group. Plans are afoot to produce 10,000 cars per annum initially, increasing it to 1 lakh cars per year in phases, says Tripathi. The EV unit in India, which may become the first independent electric car manufacturer when it goes on steam, is planning to first start manufacturing e-SUVs and follow it up with e-sedans and e-hatchbacks.

The company plans to pump in about ₹200-500 crore in 2-5 years to set up the factory, says Tripathi, adding that they are in talks with the UP government, with a target of 12-18 months to start operations. The cars manufactured at the ModiCiti plant will also be exported to Asean and other world markets.

SEV may also venture into retail sales of its EVs in India, says Tripathi. Charging points and after-sales service will be set up in Lucknow, Agra, New Delhi and NCR Region and expanded later.

Into the future

Startups are pulling out all the stops to bring about the disruption of the next decade. Potential customers expect long-range EVs, freedom from range anxiety, higher top speeds, faster charging time and a robust charging network to make the shift to EV viable.

“The EV market is a wild guess right now. There is a lot of uninformed optimism, earlier seen in dotcom. As time goes by, there are bound to be a lot of dead bodies left behind and the ones that survive will do well,” says Krishnan.

While these companies work hard, the Centre and states need to motivate them to stay the course for the long haul. “The optimism will be lost if there is no early success for startups. Given the right climate, resources and policy interventions, startups can do a wonderful job. If done, they can become an integral part of the ecosystem,” says Sohinder Gill, director, corporate affairs, Society of Manufacturers of Electric Vehicles.

What will happen when the big boys enter the field? “It will be a win-win situation if the big players can incubate startups,” says Gill. “The combined forces can help create a big and positive environment for the Indian EV ecosystem.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)