How to Become a Reflective Leader

The former chairman of Goldman Sachs describes how to become a more reflective leader

You believe the key difference between successful executives and those who are less successful is the way they deal with periods of confusion and uncertainty. Please explain.

Some people are under the impression that highly-successful leaders enjoy a smooth path, but that is not the case. Every executive -- no matter how successful -- goes through difficult periods: they experience adversity, failures and disappointments. The trick is not to avoid those things completely, it’s to learn how to deal with them. And the best way to deal with them is not to pretend that you have all the answers. You have to be able to step back on a regular basis and ask questions -- the right questions -- and to reflect in order to get yourself back on track.

You have found that when leaders struggle, there is often a mismatch between how they are spending their time and the most pressing needs of the business. Why does this happen?

In the chaos of things, people often fail to take a step back and ask two key questions. First, What is my vision for this enterprise? A vision is a clear articulation of what you would like your enterprise to be if you succeed. How does it add value to its constituencies? What service or benefit does it provide? Related to that, what is its distinctive competence -- what is your company truly great at? It pays to ask these questions regularly, because the world is constantly changing. The way you added value two or three years ago may not be relevant today.

The second critical question is, What are your top three-to-five priorities for achieving this vision? I always try to bring people back to these questions, because when someone is struggling, it is very likely that they are unclear about these two things.

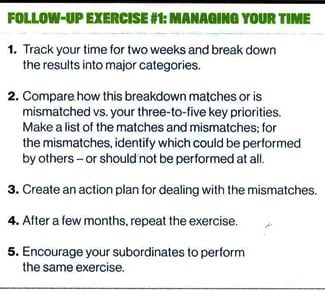

What’s the best way to go about matching one’s time with organizational priorities?

People fail to manage their time well for a variety of reasons. They may be disorganized or scattered, but I often find that they simply fail to decide in advance how to spend their time. The way to do that is, as indicated, to first identify your vision and the resulting top three-to-five priorities. I suggest putting these up on your wall -- somewhere where they are highly visible to you, so that as time passes you can regularly ask, Is my time expenditure matching up with these priorities? And, if not, why not?

You’ve also come up with a simple way for leaders to figure out if they’re in the wrong job. Please describe it.

I say to people, whatever job you are in, what are the two or three most important things that a person has to do really well to be great at that job? And my next question is, do you like doing those things? If the answer is no, you have to face up to the fact that you might very well be in the wrong job.

You have noted that many smart people spend too much time being ineffective. Why is that?

Again, it’s probably because they aren’t intentional enough about articulating their vision and priorities, and as a result, they’ve gotten into bad habits: they do what they’ve always done, they are reactive and they respond to things as they come at them. If you don’t identify your vision and priorities regularly, your activities are going to be driven by external forces and people coming in and pulling you in different directions. The best leaders exert some discipline over that.

Talk a bit about the importance of delegation to reaching optimal leadership.

If you’re not willing to delegate, it is going to be very difficult to match up your time with your priorities. The fact is, if there are really only three or four top priorities, why are you spending so much time on all these other things that are not priorities? You should be delegating many of those other things to someone else. For a lot of people, it’s a control issue: they think they will always do the task better themselves, and they fail to realized that delegation is the way to train and develop people. This is one reason I always say that leadership must be learned, because delegating is not a natural thing for people. If you are super-talented and you’re the smartest person in the room, why would you ever delegate anything? I try to get people past that – to realize that their priorities should heavily dictate how they spend their valuable time.

You have said that many of your most stressful experiences at Goldman Sachs occurred in connection with the bi-annual round of partner promotions. Why is that?

In a professional services firm, people are your most important asset: you train them, coach them and nurture them. Basically, you guard them with your life. The promotion process is a positive aspect of that, because some people get promoted; but unfortunately, a lot of people don’t, and you don’t want to lose them. You can’t promote everyone, so you have to consider, What is our vision? What are our priorities? You’re making brutally-tough choices between great people – so you better make choices that fit with the organization’s vision and priorities. Doing this is not easy: I lost a lot of sleep over that.

Many people confuse the terms coaching and mentorship. Please summarize the important differences between them.

In my experience, mentoring involves an individual telling his or her mentor a story, and the mentor giving advice based on that story. The problem is, the advice given is only as good as the story that is told. How often do you tell a story about a relationship issue to somebody who wasn’t there, and based on the way you tell it, the person says, “Oh, you definitely did the right thing”; whereas if they had been there themselves, they might have had a completely different reaction.

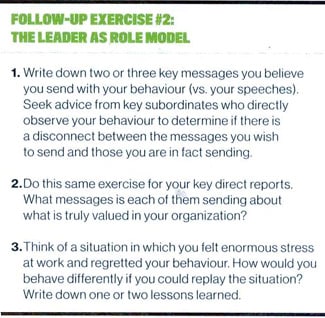

Coaching is very different from mentoring in that it requires direct observation. It’s about getting advice from somebody who directly observes you. We all need coaching because we all have blind spots: the way I perceive what I did and the way you observe what I did may not be the same. That’s why I always say to people, “You have a mentor? Great. But that is not a substitute for getting coaching.”

Coaching is likely to involve a greater degree of confrontation. How should managers prepare for this?

Many people who are otherwise very effective are not good coaches, and part of it is because they fear confrontation. Sometimes they just don’t know what to say. I advise people that coaching must be skill-based. It needs to be specific, and it needs to be actionable; giving someone vague generalities is not good coaching. I advise people to prepare, so they can go into a coaching session with two or three skill-based observations and be willing to give the person actionable advice about how to address the issues.

Coaching takes a lot of time and preparation. Sometimes people have too many direct reports or they’re spending time on other ‘priorities’, so they don’t make time for it. But I would argue that if you’re a leader, attracting, retaining and developing superb people will always be one of your top three to five priorities, and you need to spend time on this accordingly.

You have said that a key difference between successful and unsuccessful enterprises is ‘what they do with their talented people once they join the firm’. In your experience, what do they do differently?

It’s not just about how companies treat their ‘best people’. I would argue that outstanding firms strive to treat al employees fairly – which means coaching people and giving them feedback. The fact is, you don’t actually know who your best people are going to be when they join the organization. You may think you know, but sometimes it takes years, and people develop at different speeds. In a big organization, there may be a multitude of different jobs that a particular individual could fit into; your job is to assess your people, coach them, understand what they’re interested in and see if you can match them to the jobs in your firm. That’s how to build a great organization.

Another of your recommendations for leaders is to “create space for reflection” in their lives. What does this entail?

It basically means that you can’t be going full throttle all the time. There needs to be time to think. As I’ve indicated, you ought to be thinking about your firm’s vision, distinctive competencies and top priorities, and whether the organization is aligned to achieve these in its current state. You can’t do this all by yourself, so you might think about having an off-site or giving a group of your top people an assignment where you engage them by asking these very questions. That’s what I mean by reflection.

Too many leaders don’t make time for this. They don’t engage with people, and they aren’t open to learning. They think they are, but they’re not. My goal is to help people overcome the isolation that can come with leadership and give them a roadmap for how to keep learning. You don’t need to be superman or wonder woman, but you do need to be open to learning and asking questions.

The Seven Areas of Inquiry for Leaders

Vision and priorities: It is critical to have a clearly articulated vision and accompanying key priorities that are widely understood throughout your organization.

Managing your time: Do you know how you spend your time? Does it match your vision and key priorities?

Giving and getting feedback: Effective coaching is a critical tool for achieving your vision and priorities, yet most leaders do not effectively coach their subordinates. In addition, many leaders fail to get the critical coaching that they themselves need to excel.

Succession planning and delegation: Do you have a nucleus of talent that you are focused on developing? Are you consciously delegating key tasks to these people?

Evaluation and alignment: Are you pursuing practices that worked at one time but urgently need to be updated or scrapped?

The leader as role model: Are you fully aware of the messages you and your direct reports are sending with your behaviours? Do you say one thing but contradict the message by doing another?

Reaching your potential: Do you know your own strengths, weaknesses and passions? Do you foster a learning environment where your subordinates can reach their potential?

Robert Steven Kaplan is Senior Associate Dean and a professor of Management Practice at Harvard Business School. He is also co-chairman of Draper Richards Kaplan Foundation, a global venture philanthropy firm and author of, What to Ask the Person in the Mirror: Critical Questions for Becoming a More Effective Leader and Reaching Your Potential (Harvard Business Review Press, 2012). Prior to joining Harvard in 2005, he was vice-chairman of the Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

[This article has been reprinted, with permission, from Rotman Management, the magazine of the University of Toronto's Rotman School of Management]