Forget stock market forecasts. They're less than worthless.

Many Wall Street strategists are flagrantly inaccurate and about as reliable as a weather forecaster who always calls for balmy sunshine in a city where it rains or snows a lot

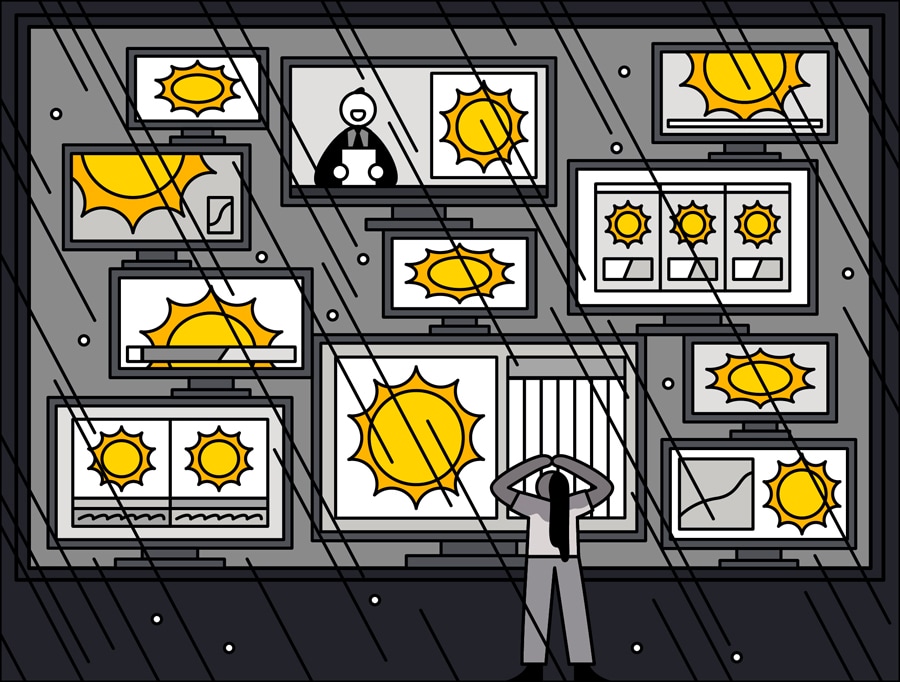

Wall Street strategists are issuing predictions for 2020. Ignore them, our columnist says, and invest with cheap, diversified index funds. (Rose Wong/The New York Times)

Wall Street strategists are issuing predictions for 2020. Ignore them, our columnist says, and invest with cheap, diversified index funds. (Rose Wong/The New York Times) It is the time of year for predictions and I’ll make one: You will be better off ignoring the Wall Street stock market predictions for 2020.

Strategists, some of whom are smart, are issuing precise predictions for where the market will be in 12 months and they look authoritative.

The record shows that they are not as rock-solid as they appear.

In fact, many Wall Street strategists are flagrantly inaccurate. They are about as reliable as a weather forecaster who always calls for balmy sunshine in a city where it rains or snows a lot. It is true that they are right about the market’s direction more often than they are wrong. But that’s only because most of them say the market will rise in the next year, which happens about 70% of the time.

The more specific forecasts — like how high or low the market will go in a given year, and whether it will lose half its value or rise 30% — should be treated as fiction.

I’m not exaggerating.

Paul Hickey, a co-founder of Bespoke Investment Group, crunched the numbers for me, updating calculations that I cited four years ago. Sadly, the forecasters are no more impressive now than they were then.

For every calendar year since 2000, Hickey compared the annual Wall Street consensus forecast in late December with the actual level of the S&P 500 one year later. He found that, on average:

— The median forecast was that the stock index would rise 9.8% in the next calendar year. The S&P 500 actually rose 5.5%.

— The gap between the median forecast and the market return was 4.31 percentage points, an error of almost 45%.

— The median forecast was that stocks would rise every year for the last 20 years, but they fell in six years. The consensus was wrong about the basic direction of the market 30% of the time.

Hickey found that the forecasts were often off by staggering amounts, especially when an accurate forecast would have mattered most. In 2008, for example, when stocks fell 38.5%, the median forecast was typically cheery, calling for an 11.1% stock market rise. That Wall Street consensus forecast was wrong by 49.6 percentage points, and it had disastrous consequences for anyone who relied on it.

But there is a more reliable and a simpler way to make investing decisions, one that doesn’t rely on putative forecasts. It is based instead on long-term historical data on the broad returns of the stock and the bond markets.

They show that stocks outperform bonds over extended periods, but that stocks are far more volatile than bonds. Holding both stocks and bonds makes sense because they tend to buffer one another.

Investing over the long run through low-cost index funds in a broadly diversified portfolio is a reasonable approach for most people. This is standard wisdom among many experienced hands in investing, and Jack Bogle, the founder of Vanguard, made it a viable strategy for great masses of people by starting the first commercially available index fund. Of course, Warren Buffett recommends this approach. And so does David Booth, the co-founder of the firm Dimensional Fund Advisors and the benefactor for whom the University of Chicago Booth School of Business is named.

Booth doesn’t make market forecasts, nor does his company, which was built on the research of economists like Eugene Fama, a Nobel laureate in economics at the University of Chicago.

“We don’t try to forecast the future,” Booth told me in a recent conversation. “We have no ability to do it. Nor does anyone else.”

Instead, Booth says, forget the forecasts — and, for the purpose of investing, forget about the current news, too. He doesn’t recommend picking individual stocks or bonds.

Keep it simple, he said, and don’t try to outsmart the market. Take on only as much risk you can handle.

“When you have some money to invest, put it into low-cost, diversified index funds,” he said. “Find a stock-bond mix that you are comfortable with. And if you realize you’re not comfortable, change it until you are — and then stick with it for years, and do better things with your life than worrying about where the market is going.”

One way of thinking about risk is to imagine that a terrible downturn is about to occur, he said. “It will happen, if you live long enough. You can count on that.”

If you are a conservative, older investor, as he is, he said, you might consider a portfolio with 25% stocks and 75% bonds.

Consider the worst stock downturn in our lifetimes, from October 2007 through February 2009, he said.

In that horrendous period, when global markets fell 55%, this hypothetical conservative portfolio would have lost about 13.5% — and recovered all of the lost ground within 7 months. “When you look at the numbers,” he said, “you may think, ‘I can deal with that and sleep at night.’”

If you are younger or more aggressive in your investing, though, you might want to try a portfolio with more stock in it — say, 60% stock, with the remainder in bonds. But be aware that in the 2007-09 market catastrophe, that portfolio would have lost about 35.6% and have required two years to recover entirely.

Because the bond market has been unusually strong, the conservative portfolio gained about 5.2%, annualized, over the 20 years through September; the more aggressive one gained slightly more, about 5.3%.

There are, of course, no guarantees that these returns will be duplicated in the future, Booth said.

“What this is, I think, is a reasonable approach to the future, based on the record of the past,” he said.

One thing it is not is a forecast.

©2019 New York Times News Service