Gul Panag: Does Marriage Still Tie an Actress's Career in Knots?

Kareena Kapoor and Vidya Balan got married recently. Does that mean the end of their careers?

In the last few months, two of Indian cinema’s leading leading ladies got married. They’re both talented, in great health, very attractive and at the peak of their careers. Will they fall prey to the accepted wisdom that marriage deals a death blow to the career of an Indian actress?

People in the know say it is inevitable. But really, is that true? And who’s to blame? Our audiences? Or are wary producers second-guessing what audience want and, more importantly, don’t want? Or, does the leading lady herself change her priorities?

First, let’s look at our country.

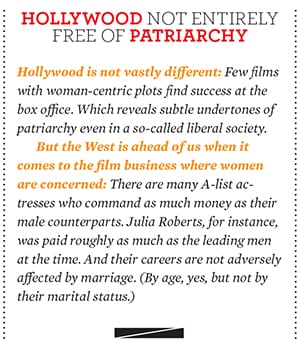

Women are marginalised in our society. And cinema, an art form, is a mirror to the larger world. A natural corollary is that our cinema—and film industry—are male-dominated. While the patriarchy is less overt in society at large, in Indian cinema it is blatant.

For those who like to argue that things are changing, all I can say is that the two or three women-centric films a year are the exception, not the rule. Instances of leading ladies playing significant characters are few and far between.

We depict, by and large, women as whimpering, simpering creatures, whose purpose is to be the love interest of the hero. And, of course, to titillate. A majority of films have a virile hero at the centre of the plot. He has a love interest, or wins the affections of a pretty young thing by any means, including, but not limited to, chasing her and interpreting her refusal as a challenge! The female lead role demands just a pretty face and a sexy body. And that is the extent of involvement of the actress in the larger plot of the film. Because of the nature of roles available, actresses are forced to bank on their sexuality and youth as qualifications.

As one producer explained, it’s simply because that’s what the audience wants. Ergo, the audience doesn’t want to see a woman depicted as being independent, having a personality. At some level they identify with the hero. If the hero desires the heroine, so do they. They see women as objects for sexual gratification. In their heads, they feel they too can ‘have’ the heroine. They definitely want to see her dancing in skimpy clothes.

If it’s fair to say that Bollywood objectifies women, then we must acknowledge that that is what our society does too.

Taking this argument forward, audiences probably feel that once a heroine is married, they can no longer get to have her; the sanctity of marriage probably spoils the fantasy. Whatever the reason, while they appear happy to accept leading men in their forties, married or otherwise, they don’t seem to accept actresses in the prime of their youth as heroines once they marry.

As a result, ‘traditional’ film-makers second-guess audiences, assuming they are not mature enough to distinguish between on- and off-screen personæ and will reject women who are no longer ‘single and available.’

This stereotypical notion is however being challenged by newer producers and actors. Another producer I spoke to felt that if actresses really want to work post-marriage, there is nothing to stop them.

Look at Suchitra Sen and Sharmila Tagore, who continued to work as leading ladies after they were married. Then there was Dimple Kapadia coming back to set the screen on fire, and Hema Malini. More recently, Kajol and Malaika Arora Khan continue to dazzle us, despite being married. There’s also Chitrangada Singh, a unique example of a leading lady who started her career as a married woman.

These exceptions apart, the ride for everyone else hasn’t been smooth. Once married, it is believed, actresses have to be content with character roles: Mothers, sisters or bhabhis. Look at Rakhi, who played mother to the very heroes she previously romanced!

And it must be said, that it is often the women themselves who voluntarily take time off from their careers, to have babies, or to just take a break. From the point of view of our Indian society, when she decides to get married she moves one step closer to playing one of the roles that only a woman can play: That of a mother. Why grudge her that? Especially in light of the biological clock. When she feels ready, she can choose to come back, as so many have done successfully. However, if she marries and wants to continue to work as before, there should be no perceptible change in her career.

Such actresses often come back to acting, like Sharmila Tagore did, or as Juhi Chawla and Kajol have. But the nature of their roles—in keeping with the sanctity of marriage, perhaps?—undergoes a change, both at their behest and that of the producers.

Very often being married places certain restrictions on the kind of work actresses choose to do. They may not take up roles that need a lot of travelling, away from family. Or roles that require overt sexuality and intimacy may be tough to fit into, as they may feel awkward to be seen romancing another man despite being married (again, assuming the audiences can’t distinguish between a film role and real life). Or the actress’s husband or his family may also have an issue with such roles.

The last part is a big reason actresses refrain from the sensuous roles, featuring item numbers, that they may have essayed in the past. Since most mainstream blockbuster films only have that kind of female star role, married women may choose to stay away from them. Thus perpetuating the myth that married women don’t get plum roles. (Again, the definition of a plum role may vary. Some may consider a role opposite an A-list star twice their age as plum, others might prefer the roles themselves be meatier.)

For actresses known for sexiness and nothing more, marriage can finish careers. But those who have distinguished themselves for their acting abilities rather than just their looks probably won’t face this problem; Shabana Azmi is a great example.

Or Vidya Balan. Most of her films have had her play non-traditional roles: Not much dancing around trees or simply being the hero’s romantic interest. By design or default, her choice of work has had her play parts that are significant to the plot as a contributing character, not just as a woman. Her roles, and the way she played them, had a quiet dignity about them. Even The Dirty Picture; any other actress, and the film could have turned into a sleaze fest. Audiences, male and female, find her easy to identify with, and relate to. She doesn’t come across as an unreal celestial being. I feel Vidya’s career is unlikely to be affected by her being married, as her body of work is based more on performance and less on any sexy, nubile image. Whether she will do another The Dirty Picture, though, remains to be seen. Kareena Kapoor, on the other hand, has had a career largely dictated by the demands of the traditional Hindi film industry, that has seen her essay mostly romantic leads opposite big stars involving the stereotypical song and dance. She has chosen parts, with a few exceptions, that don’t showcase her enormous talent. As an in-demand actress in a profit-driven industry, she perhaps has little choice. All that said, I feel her career isn’t going to be impacted either. She was promoting her first post-marriage release, Talaash, as though nothing had changed. Her choice of work may change; she had already stopped dancing at weddings a while ago. She may lean more and more towards performance-oriented roles instead of the pure romantic roles.

Kareena Kapoor, on the other hand, has had a career largely dictated by the demands of the traditional Hindi film industry, that has seen her essay mostly romantic leads opposite big stars involving the stereotypical song and dance. She has chosen parts, with a few exceptions, that don’t showcase her enormous talent. As an in-demand actress in a profit-driven industry, she perhaps has little choice. All that said, I feel her career isn’t going to be impacted either. She was promoting her first post-marriage release, Talaash, as though nothing had changed. Her choice of work may change; she had already stopped dancing at weddings a while ago. She may lean more and more towards performance-oriented roles instead of the pure romantic roles.

The bottom line: Marriage needn’t impact an actress’s career. If anything does, it’s her state of mind.

I firmly believe urban audiences will happily accept their favourite actress, married or not.

The masses though will perhaps take longer to come around. Now, it’s up to a maverick producer to cast a willing married heroine in a mainstream block buster and see what the masses really want.

Gul Panag is an actor and producer who has been part of the entertainment industry for the last 13 years. She is also an activist and opinion-maker who speaks her mind.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)