How Taylor Swift dragged private equity into her fight for music rights

In an open letter posted to social media, the pop megastar had implored her fans to intervene in what might otherwise have been an obscure music industry dispute

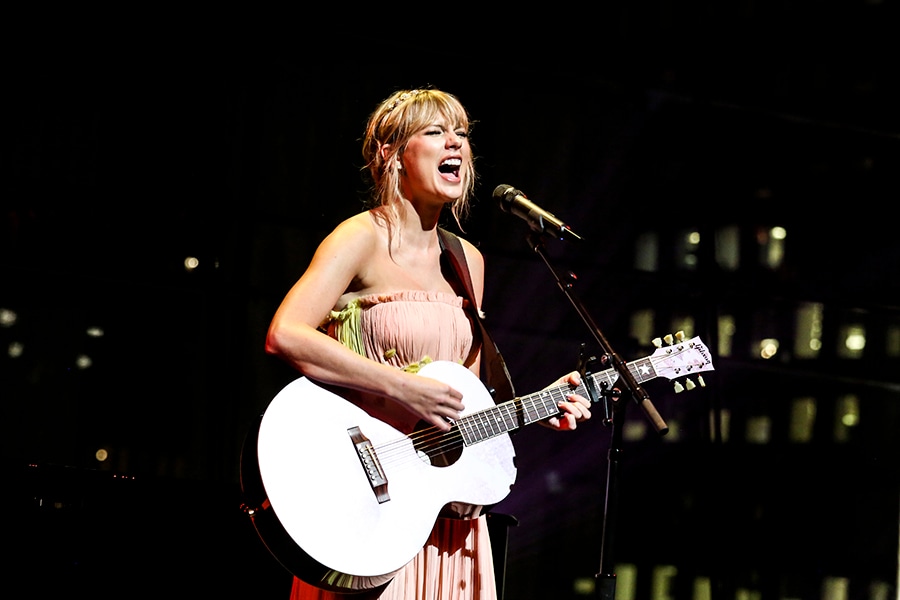

Taylor Swift performs at the Time 100 Gala at Lincoln Center in New York, April 23, 2019. The firm the Carlyle Group, a part owner of her catalog, has stepped in to encourage talks between Swift and Scooter Braun, who now controls her old label. (Krista Schlueter/The New York Times)

Taylor Swift performs at the Time 100 Gala at Lincoln Center in New York, April 23, 2019. The firm the Carlyle Group, a part owner of her catalog, has stepped in to encourage talks between Swift and Scooter Braun, who now controls her old label. (Krista Schlueter/The New York Times)In an open letter posted to social media, the pop megastar had implored her fans to intervene in what might otherwise have been an obscure music industry dispute. The new owners of her former record company, she said, were trying to prevent her from playing her old hits at the American Music Awards on Sunday night. Swift asked her followers to tell Scooter Braun, the top music manager who now controlled her music catalog, how they felt. She added that she was “especially asking for help” from the Carlyle Group, which had backed Braun’s deal for the label, Big Machine.

After Swift’s post, her fans swarmed Braun — he has said that he and his family have received death threats — and the issue even became a high-profile political talking point, with Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez using it to attack private equity.

The public callout also got the attention of Carlyle, one of the world’s biggest private equity firms, which moved quickly to encourage a deal between the two sides and urged Braun to reach out to Swift, according to four people close to the situation.

Carlyle’s intervention — which people in both camps say has brought the bitter fight closer to a resolution — says as much about the zeitgeist as it does about private equity. At a time of public outrage over corporate greed and a heightened awareness of gender-based power dynamics, the 29-year-old Swift was able to turn a commercial dispute into a cause célèbre.

According to the four people close to the discussions, a deal could take various forms, including a partnership or joint-venture arrangement. But the artist’s ideal outcome — and probably the only one she will accept, according to her team — appears to be a sale that would give Swift possession of her master recordings from Big Machine. Such an agreement could well cost her hundreds of millions of dollars.

Ownership of her master recordings, and the copyrights associated with them, would put Swift in rare company. Relatively few major-label artists — among them Jay-Z, Metallica and Janet Jackson — have gained such control, since labels typically own those assets in exchange for the risks they take in financing artists’ careers. But Swift has made no secret of her desire to control her work, which became a crucial contract point when she signed a new deal last year with Universal Music Group.

The singer’s battle with Braun and his partners at Carlyle represents an unusually public collision between a superstar’s social media power and the status quo of the music business. It has also exposed the awkward fit between artists and private equity investors more accustomed to dealing with corporate boards at large industrial and consumer companies than with popular entertainment figures.

“People in private equity look at music copyrights and think, ‘It’s like real estate,’ but it’s not,” said Matt Pincus, the founder of Songs Music Publishing, which was sold in 2017. “You’re dealing with living, breathing artists.”

Carlyle bought into Beats Electronics, Dr. Dre’s headphones company, in 2013 and made an initial investment in 2017 in Ithaca Holdings, the entertainment holding company that Braun runs. With its headquarters in Washington and its past advisory arrangements with former heads of state like President George H.W. Bush and John Major, the former prime minister of Britain, the firm is in some ways a natural mediator in the Swift dispute.

But its portfolio managers, who tend to wear dark suits and skinny ties, were not used to dealing with sneaker- and leather-jacket-wearing musicians and managers for whom business is often personal. And then, there were the obsessive, protective fans known as Swifties. While social media heat can be directed at anyone, anytime, Carlyle was unhappy to be dragged into the dispute in such a public way, three of the people said.

Swift has long railed against what she considers injustices in the music business, including past disputes with Apple and Spotify. She first went public in June with her displeasure over the deal that brought Carlyle into the picture.

On June 30, Braun, who discovered Justin Bieber and has managed Ariana Grande and Kanye West, took over most of Swift’s music catalog as part of Ithaca’s purchase of Big Machine, an independent Nashville, Tennessee, label whose founder, Scott Borchetta, signed Swift as a 15-year-old country singer. Big Machine’s ownership of Swift’s first six albums — all of them multiplatinum hits — allows it to make money anytime that music is used, whether it’s streamed by a fan or placed in a Hollywood movie.

Scooter Braun, who discovered Justin Bieber and has managed Ariana Grande and Kanye West, at his home in Los Angeles, March 7, 2018. The firm the Carlyle Group, a part owner of Taylor Swift's catalog, has stepped in to encourage talks between Swift and Braun, who now controls her old label. (Graham Walzer/The New York Times)

Scooter Braun, who discovered Justin Bieber and has managed Ariana Grande and Kanye West, at his home in Los Angeles, March 7, 2018. The firm the Carlyle Group, a part owner of Taylor Swift's catalog, has stepped in to encourage talks between Swift and Braun, who now controls her old label. (Graham Walzer/The New York Times)Ithaca paid $300 million to $350 million for Big Machine, according to two people briefed on its valuation at the time. But it also brought Swift into Braun’s orbit, stirring up heated feelings toward him largely because of his association with West, a longtime antagonist. The deal, she wrote on Tumblr, meant that Braun and Borchetta, who joined Ithaca’s board, would be in the position of “controlling a woman who didn’t want to be associated with them. In perpetuity.”

Carlyle’s stake in Ithaca was overseen by Jay W. Sammons, who runs the firm’s media, retail and consumer team. Carlyle added to its investment in Ithaca with the recent Big Machine deal. (It currently owns roughly a third of Ithaca, according to a person briefed on the size of the position.) And Sammons knew Carlyle was taking on exposure to an outspoken pop figure in Swift. But given the substantial value of her music catalog and the chance to invest in other Big Machine label artists, including Reba McEntire and Florida Georgia Line, he saw it as a compelling opportunity, a person familiar with his thinking said.

Soon after the deal was signed, Swift threatened in interviews to make new recordings of her old songs, potentially devaluing Braun’s investment in her original catalog. Braun and Borchetta accused Swift of bending the facts to fit a victim’s narrative, and said that she had rejected attempts to negotiate over the past six months.

Then, on Nov. 14, the pop star published another Tumblr post. Braun and Borchetta had essentially told Swift to “be a good little girl and shut up,” she wrote. The two men were imposing “tyrannical control” over her, she added, threatening to block her American Music Awards performance and refusing to license her music for a Netflix documentary in the works.

Swift’s note sent Swifties on a passionate mission to familiarize themselves with the Carlyle portfolio. Some shared clips from the socially conscious comedian Hasan Minhaj in which he discussed the company’s investments and its connection — through its ownership of the aerospace component manufacturer Wesco Aircraft Holdings, which supplies parts used to make a combat aircraft — to Saudi Arabia’s war against Yemen.

“When you think about it, you either support Taylor Swift or the war in Yemen,” one fan wrote on Twitter, earning more than 3,700 retweets.

Sammons soon saw Swift’s post on his phone. Concerned by the turn things had taken, he rolled into action, according to two people familiar with his role, contacting Braun and others to see what could be done to assuage Swift — potentially even by selling her masters back to her. Shortly thereafter, both public and private overtures were made to Swift, inviting her to explore an outcome that would satisfy all parties.

On Friday, Braun used Instagram to publish his first public statement on the matter, urging Swift to consider her role in the threats facing his family. But he added that he hoped to “come together and try to find a resolution,” adding: “I’m open to ALL possibilities.”

Despite Braun’s open-minded public stance, he may be reluctant to sell. Big Machine is a crucial part of a larger strategy to expand the reach of Ithaca, which has investments in music publishing, artist management and even a film studio, Mythos. Big Machine would also help establish Braun, 38, as a mogul in the style of his hero, David Geffen, who controlled his own major record label and became a top Hollywood producer.

Private equity has long been a part of the financial backdrop of the music industry, with mixed results. Some deals have gone well; in 2013, for example, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts doubled its investment in BMG, the recorded music and publishing company, after five years.

Others have been disasters. Terra Firma Capital Partners paid about $8 billion for EMI in a highly leveraged deal in 2007, shortly before credit markets collapsed. The deal fell apart four years later, but by then Terra Firma had already alienated top artists with a tone-deaf approach to cost cutting. Paul McCartney, the Rolling Stones, Radiohead and other stars fled the label, some with harsh words for its management.

Pincus, the music publisher who now advises a financial firm, put it this way: “The question of whether the power of a global superstar can wildly swing the asset value of music is hard to quantify in a spreadsheet.”

©2019 New York Times News Service