MF Husain's 'Last' Works

The master's works on the Indian civilisation, commissioned by the Mittal family, goes on view at London's V&A

At 93 years of age, MF Husain could have been forgiven for calling it a day. But when he sought exile from India in 2006—on account of the vandalisation of his works and the stress of presenting himself in small-town courts all over India, where cases of obscenity had been filed to harass him for having had the temerity to paint goddesses in the nude—he sought not retirement but revalidation.

And that came easily for, arguably, India’s most popular artist. In spite of his advanced age, the royal family of Qatar commissioned him to paint an epic series on the Arabic civilisation for the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha. And in London, the Mittal family—which had gifted the city the controversial ArcelorMittal Orbit ahead of the Olympic Games—seized the opportunity to ask him to paint a tribute to Indian civilisation.

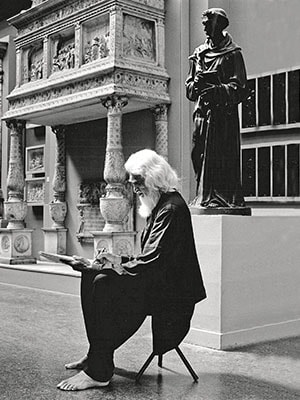

That should have been enough to keep most artists busy, but Husain, missing familiar places and faces in India, was known to have painted extempore at the homes and offices of a large number of Indian families, demanding nothing more than affection and a home-cooked meal in exchange for a hastily improvised drawing or painting. He would appear at the doughty Dorchester, where the staff invoiced him for scribbling figures on its pristine damask napkins. In Mayfair, where he had a studio, the white-haired and often barefoot artist became a familiar sight for Londoners bemused that he should carry a large paintbrush with him as an indication of his profession. At the venerable Victoria & Albert Museum, like scores of art students on any given day, he could be seen sketching on his pad at the Ironwork Gallery, unaware of the chuckles he inspired among visitors ignorant of his fame but conscious only of his age.

It is from this phase of his life, spent in Doha, Dubai and, in particular, London, that a number of ‘last’ works by the artist are gaining currency.

Most, understandably, are not for sale; they are the legacy of families who befriended him in an alien city and extended warmth and hospitality. Though Husain was wealthy—if his collection of sports cars and bikes is any indication, he was extremely rich—money was something he rarely carried on him, so his art became the currency of exchange for favours rendered. The right-wing parties that had hounded him in India enjoy the support of many non-resident Indians, but in London Husain seemed not so much offensive as vulnerable. Secretly, they clamoured for his works, so even though prices were falling back home—or, at least, they were failing to keep pace with modernists SH Raza, FN Souza, Tyeb Mehta and VS Gaitonde—his popularity never waned. Because he still had a large inventory of unsold canvases, he was not required to paint to eke out an existence, however luxurious. The sale of those works—this writer is privy to some of them—now afforded him the comfort to paint in a manner and style of his choosing.

Some of these ‘last’ works, the ones commissioned by Usha Mittal, will now go to the V&A’s gallery 38A for a viewing as ‘Master of Modern Indian Painting’ from May 28 to July 27. According to a spokesperson, even though Husain is “not very well-known” in London, “this exhibition will rectify that”. The V&A had been in conference with the Mittals about a number of projects, and it was natural that the First Family of Steel should suggest the Husain exhibits as a starting point for that venture.

Husain wanted to paint 31 triptychs or 93 panels to express his vision of India, a country that he referred to as “a museum without walls”. Among the peers of the Progressive Artists’ Group, Husain alone, among the founding members, chose to paint a holistic view of Indian society from the vantage of the street, often portraying myths from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, but also singers, dancers, musicians in a manner that some described as expressionistic while others dubbed it primitive impressionism. Wrongly called ‘the Picasso of India’—that sobriquet better suiting Souza—Husain was maverick, manipulative, marketable, as popular for his remarkable talent as his ability to command the media. He mocked the press, made films with popular film stars, and was quick with repartee, a one-man act that became the face and form of modern art in India from the 1950s till his death in London in 2011.

Critics and collectors claim his best works were done in the early decades, but Husain continued to reinvent and surprise himself and everyone else. Identified for his paintings of horses, he is equally well regarded for his works on Mother Teresa. He courted controversy during the Emergency, when he painted Indira Gandhi in the form of Durga riding a tiger, but was a member of the Rajya Sabha in the eighties.

An observant artist, his eye for detail livens up the Mittal canvases, even though he was at an advanced age when they were painted. Husain completed eight of the 31 triptychs before he died, each painting consisting of three 12ft x 6ft panels (or 12ft x 18ft for the triptych), and it is this unfinished collection that offers a glimpse into his thinking.

Not only did he refuse to create a linear historicity, his insistence on providing glimpses of the life and culture of India in the manner that he experienced it became the context from which he visualised the whole project. The exhibition, therefore, begins with an invocation to Ganesh, the beloved elephant-headed god who is considered a remover of obstacles, the only single panel or painting in the exhibition. The eight triptychs, which form part of his vision of India from Mohenjodaro to Mahatma Gandhi, span “mythology, architecture and popular culture”, according to Usha Mittal, who was privileged to see the artist work on the series in London.

However sure he might have been, Husain pored over books, journals and tomes to ensure that he chose the correct nuances for the triptychs.

Which other artist would have picked something as banal as Indian Households as a subject for one of those triptychs? Yet, in his hands, it becomes a comment on the co-existence of religions and faith in India with its unique syncretism. The first panel of the painting depicts a Muslim household, where the old man with the hookah could be an allegory for his grandfather, and the little boy playing under the charpoy may be autobiographical. The second panel peeps into an educated Hindu household from the south—witness the head of the family immersed in The Hindu—while the familiar image of the umbrella, another leit-motif for his grandfather, links it to the previous panel. The third panel depicts a warrior Sikh family, but not without its middle-class nuances, captured through the table clock and Singer sewing machine, voyeuristic glimpses of middle class lives in India.

It is these delightful insights that make up the rest of the triptychs. In ‘Indian Dance Forms’, the sage Bharata holds forth on the Natya Shastra, while the other two panels depict bharatnatyam and kathakali. The ‘Hindu Triad’ has, of course, Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva in their roles as protector, preserver and destroyer, while in ‘Three Dynasties’ he picks the Mauryan, the Mughal and the British Raj for their abiding influence. In ‘Tale of Three Cities’, he opts for Delhi for its historicity, Varanasi for its spirituality and Kolkata for its culture, and in ‘Indian Festivals’ he chooses Holi, Tulsi Pooja and Poornima—all Hindu festivals, the right-wingers will be glad to know—while ‘Language of Stone’ highlights the country’s—again, Hindu—sculptural tradition alongside poet-laureate Rabindranath Tagore’s poetry.

Handwritten notes describe each panel and their importance, something he discussed at length with Usha Mittal as part of a venture that, had it been completed, would have changed the visual perspective of India as well as that of its artist.

Let it be said: Husain was its most enthusiastic votary.

The Commission

Usha Mittal was principally responsible for the patronage the family extended to MF Husain when he began work on the project in 2008 in London. In this email interview, Usha Mittal shares the shaping of the series and her interactions with the artist.

Why did you choose Husain for painting this series?

Husain Sahib had a profound understanding of Indian history and culture and was knowledgeable about many aspects of life in the subcontinent, from mythology and religious beliefs to architecture, poetry, music and the visual arts. On seeing Husain's series on the Hindi film Mughal-e-Azam, I suggested to him that he should capture the history of the Indian civilisation on canvas. The conversation led to a major commission, which the artist started working on during the final years of his life.

Why pick on the Indian civilisation as the series theme?

The Indian civilisation is rich in culture and diversity, and spans thousands of years. Aspects of Indian civilisation have been represented in Husain's paintings from the start, whether folk images, rural life, dance, mythology or history. With his immense understanding of India and her culture, I felt that Husain Sahib was uniquely endowed to execute such a commission.

Did he discuss the panels with you before painting them?

He was very inspired by this project. Every time I would meet him, he would talk only about the next panel, and would ask for my opinion. In fact, he was talking and dreaming about the forthcoming panels on his last day.

Which are the other Indian artists in your collection?

Apart from Husain, I very much admire the works of Ram Kumar, Tyeb Mehta and SH Raza.

Can you share incidents

of your interactions with Husain while he was working on this series in London?

I saw him paint on several occasions. When he painted, he was totally submerged in the paintings. He had a childlike enthusiasm, and happily painted while listening to music. He had a great sense of humour, and his knowledge of Indian culture, customs and traditions was commendable. Before he started painting the history of India, he read several books on Indian history, and spent several weeks analysing and determining what he wanted to paint and how. He decided he wanted to paint 31 triptychs, but unfortunately could complete only eight. I always admired his qualities as a painter.

Husain’s worth, or the worth of a Husain

Despite a fall from grace, he cared about his legacy

Image: Amit Verma

A Husain (left) and a Souza displayed on the same wall at the Christie’s auction in Mumbai last December

That he was prolific has never been in doubt, and observers have speculated about the number of paintings he painted in his lifetime: Variously between 20,000 and 40,000 works, which record has a parallel with that other equally productive artist, Pablo Picasso.

Husain was always conscious of his value, using it as a benchmark of his talent as well as his popularity. Early in his career, he would sulk if Raza’s prices at an exhibition were marked higher than his, removing his own works on one such occasion. He did see Raza’s prices, as well as those of Souza’s and Tyeb Mehta’s, best his own in his lifetime, by which time he was concentrating harder on his painting, knowing that time was now against him as he raced to complete commissions that would result in a unique legacy of art.

Even so, for decades he enjoyed the distinction of being India’s most expensive artist, and the movement of Husain’s works in galleries and at auctions has always been brisk. With his most iconic works in museums and in collections that are unlikely to sell, it is only those works in the market that determine his benchmark.

For now, his top canvases do command prices in the region of Rs 2–5 crore. Since uniqueness and provenance adds value to an artist’s worth, his triptychs for the Mittals could be among the more expensive of his works, though Usha Mittal has refrained from commenting on the commission’s value, only commenting that it was “a private matter between Husain Sahib and myself”.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)