The Best Whiskey in the US, from Under a Bridge

Want to find the best single malt whiskey in the world? Look under a bridge in Waco

A quarter-mile from downtown Waco, Texas, in a neighbourhood of long abandoned storefronts, is a small, rusted-metal shed beneath the 17th Street Bridge. It sits between the overpass’ support pillars, next to a white trailer. It’s a safe bet none of the drivers know they’re speeding over the worldwide headquarters of Balcones Distilling, the maker of the finest new whiskey in America.

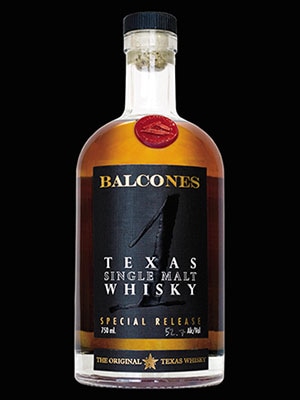

Founder Chip Tate stands inside across from two handmade copper stills. Tate dips a glass pipette into a vat and pours the liquid into tasting glasses. It is the unmatured form of his Texas Single Malt Whisky—the drink that put Balcones on the map.

Balcones’ arrival was first heralded by its distiller-of-the-year awards in 2012 and then by the single malt’s firstplace finish in the 2012 Best in Glass competition, a British contest that names the best whiskey released each year. Balcones was the first American distiller to capture the highest honour, defeating such venerable brands as Johnnie Walker, Macallan and Balvenie.

So how did a small distillery in Waco rise to the top of the whiskey world in only six years? In part Balcones’ success is the result of America’s love affair with all things artisanal. Only 68 craft distillers existed a decade ago. Today there are 623, at least one in every state.

It’s a crowded space, but Balcones has been able to stand out. Partly it is due to Tate’s story as a Texas pioneer. He has long been fascinated by mixing different ingredients. As a child in rural Virginia he made explosives: Bottle rockets and tennis ball cannons. After college, he brewed beer or baked: “I was basically a monk.”

In 2007 Tate was a Baylor enrollment administrator dreaming of leaving the ivory tower for the copper still. With a wink and a nudge he will admit some initial experiments—presumably moonshine made at his Waco home—led him to believe he could make it as a legitimate distiller. A rudimentary handbook called Whisky: Technology, Production and Marketing became his bible; instruction at the Bruichladdich Distillery on whiskeymaking fundamentals, one meant for prospective brand ambassadors, was new-found gospel.

To launch Balcones—named after the fault that bisects Texas and provides the area with drinking water—Tate raised $100,000 in startup capital, and a real estate buddy found him the shack under the bridge.

For Balcones’ first release, Tate drew inspiration from a dessert sauce of raw sugar, honey and figs he had served at a party. And that’s what he fermented to create Rumble. Early customers appreciated its rum-and brandy-like qualities. Rumble was released along with Baby Blue, an unusual whiskey made with heirloom blue corn that tastes of apricot, sweet tea, smoked chilis and, most oddly, cotton candy. Balcones has developed another blue-corn-based whiskey called Brimstone made with Texas scrub oak to add smoke the way Islay whiskys use peat.

Tate had always been a Scotch man, though, and longed to bring a single malt to market. For what would become Balcones’ signature whiskey, Tate selected a main ingredient with a fortuitous-sounding name: Golden Promise, a Scotch-malted barley that hadn’t been used regularly in four decades. His single malt ages in custom American and French barrels. The end result has hints of vanilla, plum and pear.

It has helped Balcones win one award after another. Last year Balcones received Whisky Magazine’s Craft Distiller of the Year award (again) and cleaned up at the Wizards of Whisky competition in London, where the single malt claimed World Whisky of the Year, World Single Malt of the Year and American Single Malt of the Year. As a result, demand for Balcones now greatly exceeds its supply.

Last year the company produced roughly 5,000 cases (with capacity now at 12,500), hand-bottled down to the wax seal, and took in a little more than $1 million in revenue. (Balcones’ whiskeys typically run $60 to $70 a bottle.) Tate knows he must think bigger—a larger distillery, greater distribution and more products— to fulfill his ambitions for the company.

“It’s a great problem to have, but it is a real problem,” Tate admits as he opens the door to a six-storey building a short drive from his current distillery. The future home of Balcones is in slightly better condition than the one under the bridge. In the next year Balcones will add two new stills that will boost production to 100,000 cases. Assuming sales continue apace with greater production, that would mean estimated revenue of $20 million.

As Tate trudges through a set of dimly lit hallways he reiterates his desire for Balcones to stay relatively small and independent. “Something that’s the magnitude of a Macallan or a Balvenie,” he adds. “We’re not trying to make the Hamburger Helper of the whiskey world.”

If Balcones wants to stay independent it will need to grow closer with its distributors. A little over a year ago the company hired its first brand ambassador, whose job is to talk up the various whiskeys with distributors. Today it is in roughly 20 states, as well as in the UK, Norway, Sweden, Japan and Australia. Tate would soon like to add Canada, France and Korea.

Inside his office—the white trailer next to the shed—Tate rummages for a new treasure: One of only three bottles left of a rum he experimented with. He isn’t blind to the necessity of continued innovation, and once he has bigger stills the rum is at the top of the list of the new products he wants to make. “There’s an American brandy tradition that hasn’t been explored fully. And I think rye’s a very interesting grain. I’ve got plans, man.” He thoughtfully sips the rum. “No one wants to be the troll under the bridge forever.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)