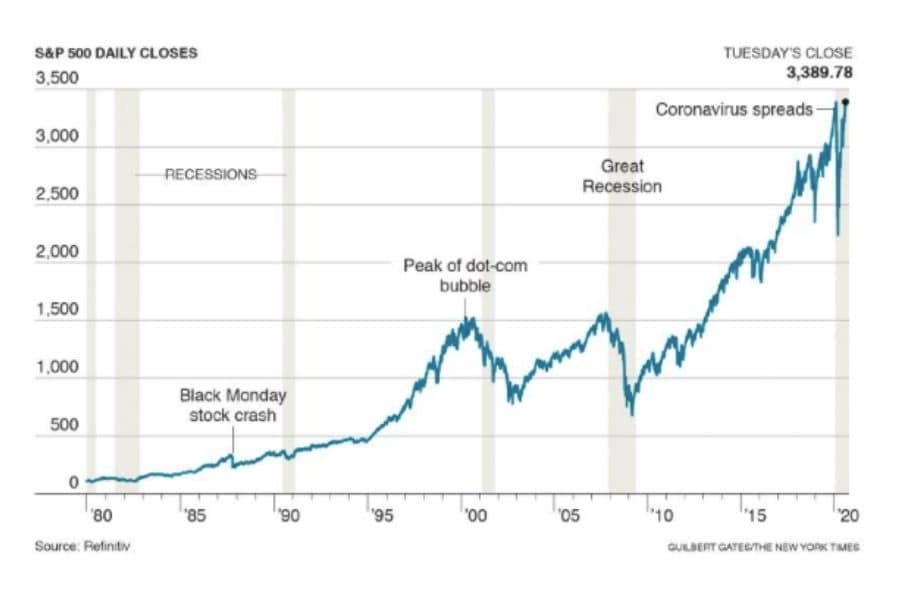

'This Market is nuts': S&P 500 hits record, defying economic devastation

Investors have cast the nearly relentless drumbeat of bad news aside to focus on any signs that the worst of the coronavirus pandemic might be over

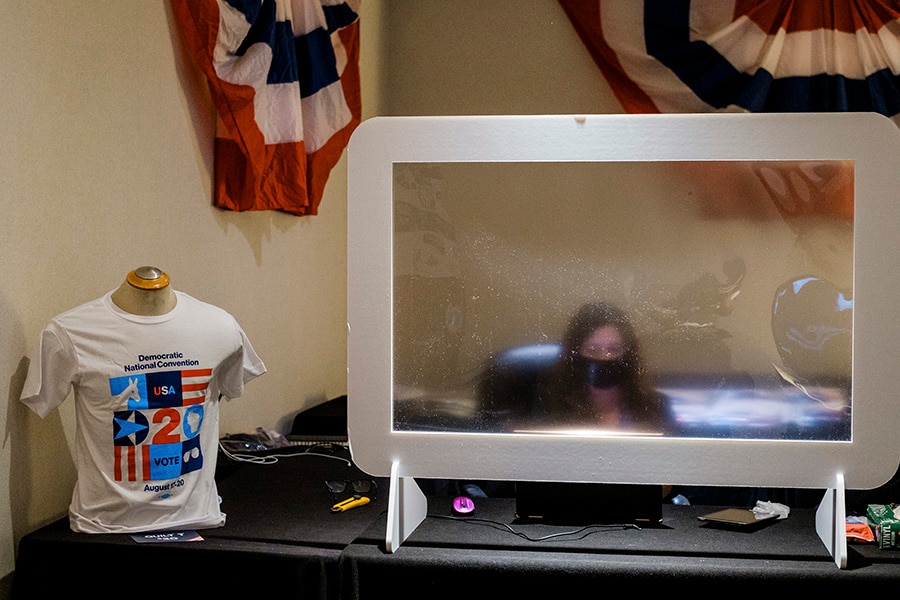

A worker sits behind a barrier at the gift shop for the Democratic National Convention at the Hyatt Regency Milwaukee in Milkwaukee, Wis., Aug. 17, 2020. On Tuesday, undying optimism propelled the market to a new high, pushing it past a milestone reached only six months ago, when the coronavirus was just beginning its harrowing journey across the United States

A worker sits behind a barrier at the gift shop for the Democratic National Convention at the Hyatt Regency Milwaukee in Milkwaukee, Wis., Aug. 17, 2020. On Tuesday, undying optimism propelled the market to a new high, pushing it past a milestone reached only six months ago, when the coronavirus was just beginning its harrowing journey across the United States

Image: Gabriela Bhaskar/The New York Times

Widespread economic devastation, severe unemployment and a grim prognosis for recovery have not stopped the stock market’s exuberance. And Tuesday, that undying optimism propelled the market to a new high, pushing it past a milestone reached only six months ago, when the coronavirus was just beginning its harrowing journey across the United States.

“This market is nuts,” said Howard Silverblatt, senior index analyst for S&P Dow Jones Indices.

To those outside Wall Street, the market’s rise may appear inexplicable given the human and economic toll of the virus, and a stalemate in Washington that has paralyzed efforts to provide more relief that many businesses and workers desperately need. Still, investors have cast the nearly relentless drumbeat of bad news aside to focus on any signs that the worst might be over. They have also been emboldened by the Federal Reserve’s steadfast support of the markets and unwavering embrace of low interest rates.

Investors are taking into account the fact that the virus, which had seen a recent surge that threatened to set back much of the country a second time, has shown signs of abating, with the number of new cases declining by 16% over the last 14 days, according to data compiled by The New York Times. Expectations for 2020 corporate profits, formulated by Wall Street analysts, seem to have stopped plummeting. Also, slow but notable progress toward a vaccine, which many manufacturers and public health experts say could be ready by next year, has made many investors bullish.

And the economy is improving, even if the recovery is tepid. Some 1.8 million new jobs were added in July, and weekly state unemployment benefit claims have fallen below 1 million for the first time since March.

Together, these data points have been enough to create an outlook that, while not exactly rosy, is at least no longer pallid. At the same time, the improvements are hardly so significant that they would prompt the Federal Reserve to pull back its support for the economy. The Fed has started new programs to buy Treasury bonds and other financial assets to calm investors and is financing those programs by essentially creating new money.

©2019 New York Times News Service