Will Notre Dame get a taste of modern architecture?

A glass or crystal spire, or a 300-foot carbon-fibre and gold leaf spire -- architects have submitted dozens of design renderings to rebuild the Notre Dame after the fire

In an undated architectural rendering, a proposal for the Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris, featuring a rebuilt roof and spire entirely in stained glass. The proposal from Aj6 Studio is one of dozens upon dozens made public since the fire. No details of a proposed redesign contest have yet been released. (Alexandre Fantozzi/Aj6 Studio via The New York Times)

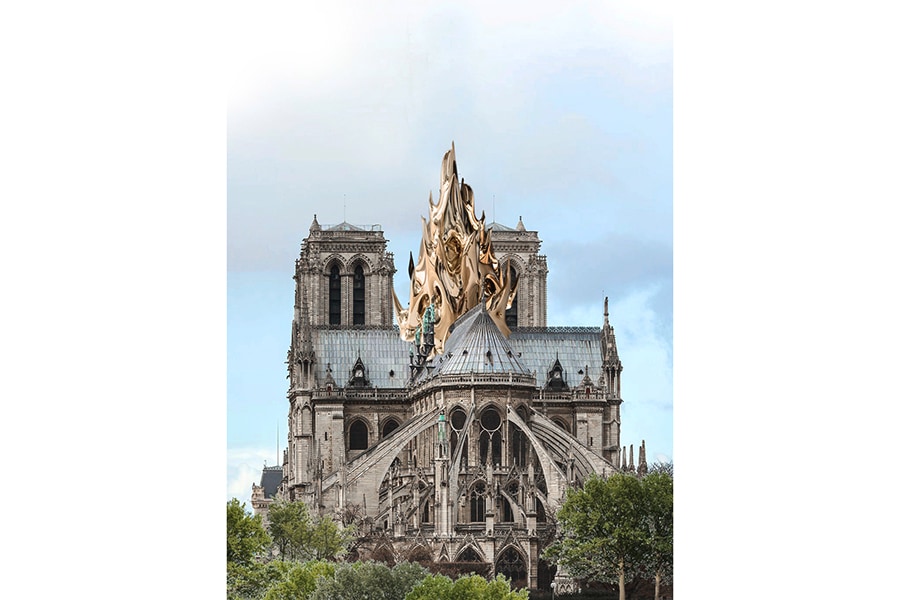

On April 23, about a week after the fire at Notre Dame in Paris, designer Mathieu Lehanneur unveiled his plan for a new spire for the cathedral: a gleaming, 300-foot flame, made of carbon fiber and covered in gold leaf, that would be a permanent reminder of the tragedy.

The suggestion, first made on Instagram, did not go down very well — some even called it blasphemous, Lehanneur said.

In an undated architectural rendering, a proposal for the rebuilt roof and spire of the Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris, featuring a 300-foot spire 'flame' rendered in carbon-fiber and gold leaf. The proposal from Mathieu Lehanneur is one of dozens upon dozens made public since the fire. No details of a proposed redesign contest have yet been released. (Mathieu Lehanneur via The New York Times)

The idea was meant as a simple provocation: to show the absurdity of rebuilding the spire as it was in the 19th century, he said. But, he added, he had since become serious about the plan.

“A few days after I put it online, I thought, ‘Why not?’ ” Lehanneur said. “The flame is actually a very strong symbol in the Bible,” he noted. “It’s powerful.”

Lehanneur’s plan is among dozens that have been made public since the fire, most of them produced by small architectural and design firms. They range from the madcap (an architectural folly that looks like a spaceship has landed on the cathedral) to the modern (a project that would turn the roof into a greenhouse).

Many of the designs are glass towers. But one, from Vizum Atelier, a design firm based in Slovakia, would see a beam of light shoot up from a new spire into the sky. It would be a “lighthouse for lost souls,” Michal Kovac, an architect at the firm, said via email. It would fulfill the aim of the architects of Gothic cathedrals around Europe who wanted to touch heaven with their spires, he added.

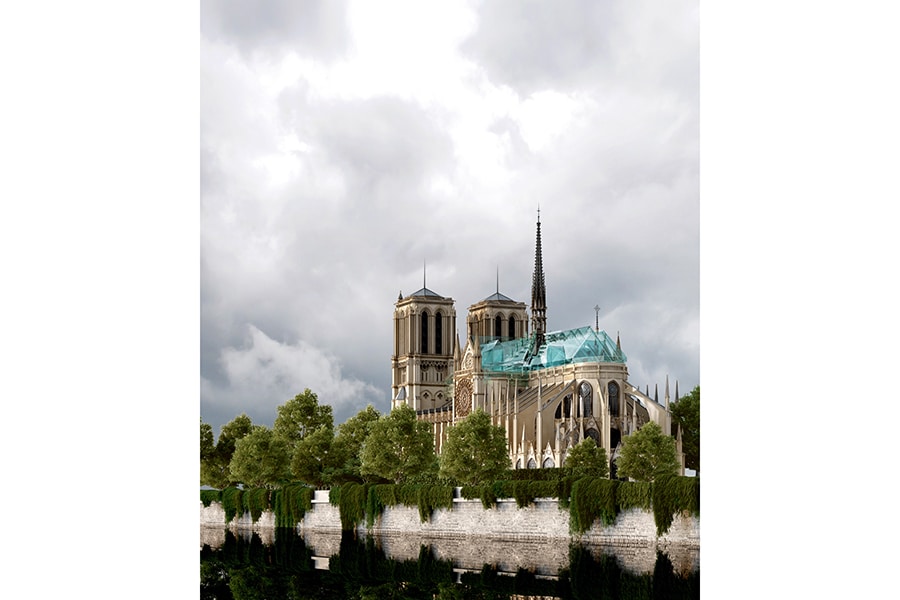

Another proposal with religious overtones came from Alexandre Fantozzi, a Brazilian architect, who envisaged the cathedral’s roof and spire being rebuilt entirely using stained glass.

A further design, by Alex Nerovnya, a lecturer at the Moscow Architectural Institute, suggested a roof resembling a diamond around a rebuilt Gothic spire.

In an undated architectural rendering, a proposal for the rebuilt roof and spire of the Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris, featuring a diamond-like roof. The proposal from Alex Nerovnya is one of dozens upon dozens made public since the fire. No details of a proposed redesign contest have yet been released. (Alex Nerovnya via The New York Times)

Several designers said that their designs were merely artistic responses to the shock of the fire. But some also hope that their plans will be chosen. Two days after the fire, Prime Minister Édouard Philippe of France said that there would be an international competition for a spire to replace the one designed by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc that was destroyed. “This is obviously a huge challenge, a historic responsibility,” Philippe said.

No details of the proposed contest have yet been released.

President Emmanuel Macron of France said last month that he was not opposed to a “a contemporary architectural gesture” that could make Notre Dame “even more beautiful.” But many in France have called for Viollet-le-Duc’s spire to be restored as it had been built. On Thursday, the daily newspaper Le Figaro published a survey suggesting that 55 percent of French people wanted the spire restored to its original form, and several politicians have pushed for an identical replacement.

A proposed law on how the restoration would be financed was to be put before the French Parliament on Friday. The law would also allow exemptions from environmental and heritage rules for the project, seen as measures intended to make it possible to comply with Macron’s stated desire to rebuild the cathedral within five years.

In response, more than 1,100 architecture professionals and art historians published a letter in Le Figaro on April 29 calling on the government to “take time to find the right way” to restore the structure and ensure that heritage laws were respected.

In an undated architectural rendering, a proposal for the rebuilt roof and spire of the Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris, featuring a crystal and glass spire. The proposal from ABH Architectes is one of dozens upon dozens made public since the fire. No details of a proposed redesign contest have yet been released. (Alexandre Chassang/ABH Architectes via The New York Times)

Franck Riester, the French culture minister, told Parliament on Friday that the restoration would “not be hasty” and that the government would listen to critics of the proposed law.

No major architect has yet issued a proposal for how they would rebuild Notre Dame, but several said they would consider entering a competition when details were announced.

“We’d certainly think about it,” Stephen Barrett, a partner at the London-based practice of architect Richard Rogers, said. Rogers was one of the architects who designed the Pompidou Center in Paris.

Barrett said the five-year deadline was unrealistic, unless a new spire was constructed elsewhere, using modern lightweight materials, and then dropped into place. But that was “not in the spirit of a medieval cathedral, which took decades and involved a lot of craft,” he added.

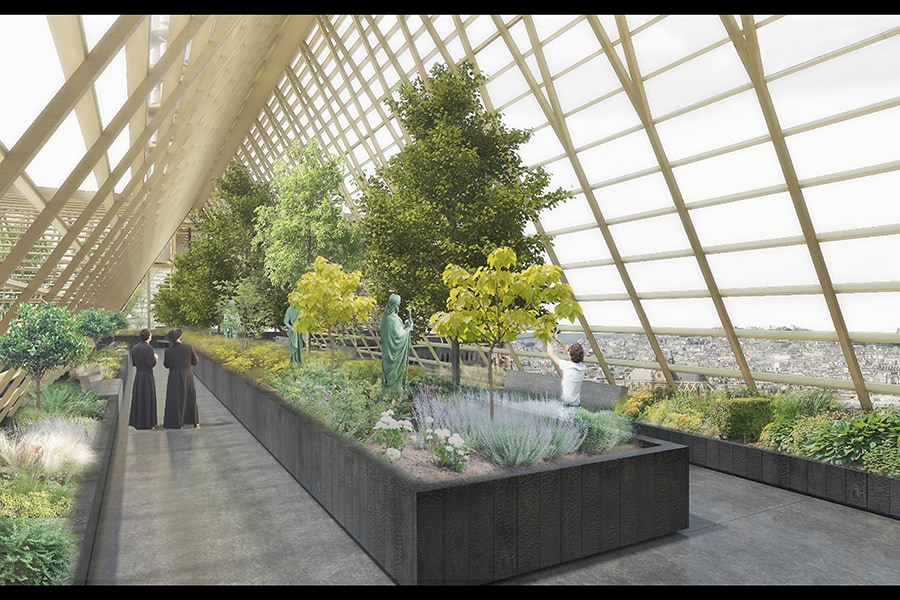

Barrett said “the most interesting” designs he had seen so far were those that involved opening up the roof and creating a new public space. Those included turning the structure into some kind of garden with trees, echoing the lattice of ancient timber beams that used to make up the cathedral’s attic and that were known as “the Forest.”

“That process of democratizing space is something we like and have done before,” Barrett said, though he speculated that the weight of trees could be too much for the cathedral.

Several designs have appeared online that look to create gardens. The greenhouse design was created by Paris-based Studio NAB and would include beehives in the glass spire. Those plans are a nod to the beehives that have long been kept on Notre Dame’s roof — the honey produced has traditionally been given to the poor. (The hives survived the fire.)

In an undated architectural rendering, a proposal for the rebuilt roof and spire of the Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris, featuring a greenhouse and beehives. The proposal from Studio NAB is one of dozens upon dozens made public since the fire. No details of a proposed redesign contest have yet been released. (Nicolas Abdelkader/Studio NAB via The New York Times)

Clément Willemin, a director at a French landscape architecture firm, posted on LinkedIn his idea to turn the cathedral’s roof into a garden with views across Paris “dedicated to all the species of animals and plants that we have been erasing off the planet.”

Willemin said that a love of nature and a desire to protect the environment were concerns that united people across the world. “In that way, it is our one and only universal religion,” he said.

Like most of the plans, Willemin’s idea has received a mixed response. But he predicted that whatever idea was chosen would cause upset. “There is no way we’ll get to a consensus and an idea that everyone is happy with. Definitely not in France,” he said.

Lehanneur, who designed the flame spire, noted that most of the landmark buildings in Paris had been contentious when they were constructed, including the Eiffel Tower, the glass pyramid at the Louvre and the Pompidou.

The objections never last long, Lehanneur said. “After one or two decades, the most conservative people not only accept them, they want to defend them,” he added.

©2019 New York Times News Service