How to know when it is time to switch to plan B

Novice entrepreneurs often make the mistake of sticking with a business plan for too long

Entrepreneurs are consummate optimists. They have to be. How else could they power through all the things that go wrong when starting a new venture?

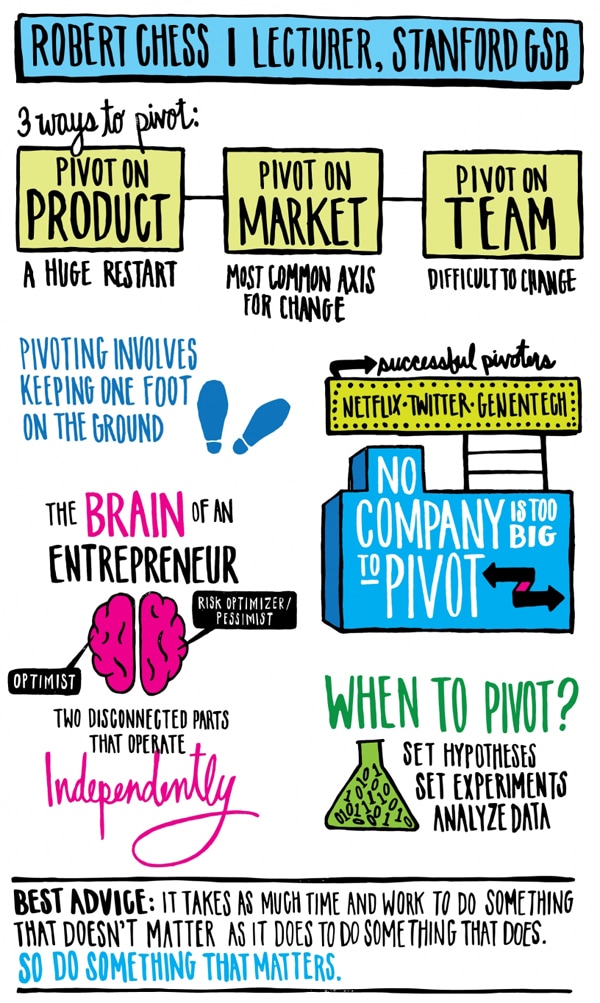

Their positive attitude, however, can also blind them to the warnings that it is time to consider plan B, says Robert Chess, a lecturer of management at Stanford Graduate School of Business.

“The first-time entrepreneurs oftentimes don’t recognize the signs that a pivot needs to be made, and (they) will stick with things too long,” says Chess, who is also chairman of Nektar Therapeutics, a biopharmaceutical company. Chess shared his thoughts with Stanford Business on how to know when to change the direction of a company following a May 1 symposium sponsored by the Center for Entrepreneurial Studies at Stanford GSB.

Use Both Sides of Your Brain

Company founders need to have a split personality: the optimist who thinks everything is going to work out and the pessimist who can be the risk optimizer, keeping an eye out for what can go wrong, he says.

“I think you have to have those two almost disconnected parts that can operate simultaneously,” Chess says.

Determine What Needs to Change

“A pivot involves keeping one foot on the ground and moving the other foot,” says Chess. That means something needs to remain constant in the company when it becomes clear that the current business plan is not working.

You may have a great product and the right customer fit, for example, but the team that’s executing it may not have the right skills to bring it to market. Or, you may have a dynamic team and a quality product, but you may be targeting the wrong market.

Typically, the area where startups get it wrong initially is the market for their product, and luckily, that is not a fatal error. It’s much easier to a find a new application for a product than to pivot on the product, which can take years, he says. Also, it is difficult to change out the team and investors. “It sounds like an easy thing, but it’s not,’’ Chess says.

When is it time to call it quits? If multiple key areas — product, market, and team — are not working,“that may be time to pack it in,” he says.

Make Change Part of the Culture

The companies that build nimbleness into their credo from the start are the most successful at making the switch to plan B.

They signal to employees and investors early on that because theirs is a start up, there will be bumps along the way, and there will be failures. A company might, for example, seek a cushion with its early investors, building in sufficient money for product experimentation, and tailoring the product-market fit.

“You have to bring your investors along. You need to bring your board along. You need to bring your employees along,” Chess says. The most important thing is having them buy into the overarching mission of company, knowing that the exact details of the product or service they provide may change over time.

“All these things that you might call ‘failure’ are really just learnings and actually are contributions to the intellectual success, intellectual base, and eventual success of the company, “ he says.

Too Big to Pivot?

Even larger, more well-established companies may find they need to change course from time to time. Netflix’s decision to stream video content as DVDs became less popular is a classic example of a product pivot, Chess says. Even in the biotech industry, where scientific research demands long product development lead times, 80% of firms are successful in areas very different from their original ideas, he says. “I don’t think any company is too large (to pivot), and every company needs to adapt.”

Trust Your Gut (and Analytics)

Entrepreneurs cannot ignore objective data; nor can they ignore their instincts.

“Steve Jobs did not make his decisions based on a lot of analytics. He was making it based on gut and based on a true understanding of what the customer would want, if it only existed,” Chess says.

It may take a while for a product or application to work out, but there are ways of testing it to make sure that the product concept and market are right, he says. “I think the key thing is setting up a lot of experiments — setting up hypotheses and finding ways of testing them.”

Then, have a trustworthy adviser outside your immediate sphere who can help you be more objective when you’re evaluating that data.

This piece originally appeared in Stanford Business Insights from Stanford Graduate School of Business. To receive business ideas and insights from Stanford GSB click here: (To sign up: https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/about/emails)