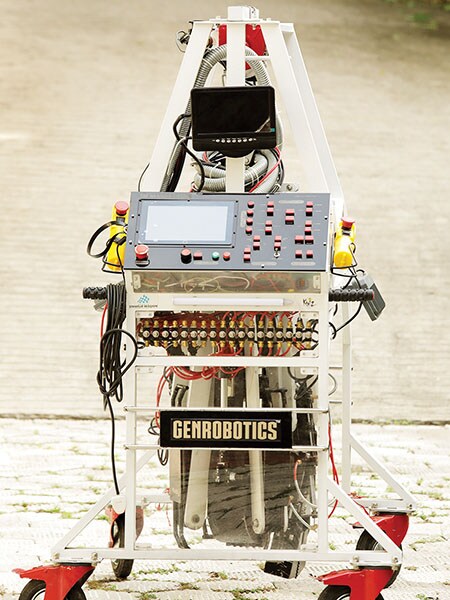

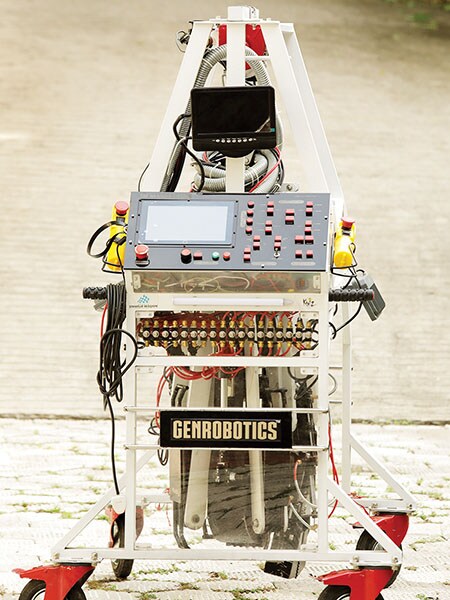

Bandicoot: Genrobotics' robot that scoops out filth from sewers

Kerala-based Genrobotics has manufactured a robot that cleans sewage; this may eventually end the barbaric practice of manual scavenging

From left: Nikhil NP, Rashid K, Vimal Govind MK and Arun George

From left: Nikhil NP, Rashid K, Vimal Govind MK and Arun GeorgeImage: Vivek R Nair for Forbes India

The warren of passages leading to the Genrobotics office in a building on the Technopark campus, on the northern fringes of Thiruvananthapuram, doesn’t even remotely resemble the dream lab of Tony Stark, the billionaire genius inventor portrayed by actor Robert Downey Jr in the movie franchise Iron Man.

There aren’t any Artificial Intelligence-enabled assistants strolling around, nor do any 3D holographic images hang mid-air; just a Transformer toy is seen sharing shelf space with a trophy, if you must identify a leitmotif. But beyond the mustard yellow walls and a slumping bean bag at the reception is a hub of activity where, inspired by the superhero, four 20-somethings are furiously racking their robotics savvy to take on a social scourge no less nefarious than any villain in the Marvel universe.

Just about a year old, Genrobotics scripted its headline act with Bandicoot, a 50-kg, pneumatic-powered, remote-controlled robot that goes down into a manhole, spreads its expandable limbs like a spider and scoops out the solid and liquid filth that block urban sewers. It has a robotic arm that, in a 360-degree motion, can sweep the floor of the manhole to collect the debris in a bucket, cleaning manholes in 20 minutes as opposed to over 2 hours that at least three workers would take to do it manually. Through its magnetic mechanism, it also lifts the heavy manhole cover on its own, a job earlier performed by multiple workers. Bandicoot ran its first successful trial in February, at the government medical college in Thiruvananthapuram, and later across the city before it was introduced to the state later that month by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan.

Just about a year old, Genrobotics scripted its headline act with Bandicoot, a 50-kg, pneumatic-powered, remote-controlled robot that goes down into a manhole, spreads its expandable limbs like a spider and scoops out the solid and liquid filth that block urban sewers. It has a robotic arm that, in a 360-degree motion, can sweep the floor of the manhole to collect the debris in a bucket, cleaning manholes in 20 minutes as opposed to over 2 hours that at least three workers would take to do it manually. Through its magnetic mechanism, it also lifts the heavy manhole cover on its own, a job earlier performed by multiple workers. Bandicoot ran its first successful trial in February, at the government medical college in Thiruvananthapuram, and later across the city before it was introduced to the state later that month by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan.

By replicating all the human actions required to clean sewage, Bandicoot has provided a viable option to end the barbaric practice of manual scavenging in which sewage workers, mostly Dalits, are dipped into mucky manholes that often emit toxic gases and overflow with liquid sewage.

Despite being outlawed by the government—through the Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act, 1993, and Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, 2013—manual scavenging continues rampantly across the country due to lack of alternatives and casteism. According to IndiaSpend, a data journalism initiative, 102 workers reportedly died in 2017 while cleaning sewer lines manually. That’s an average of over eight deaths a month.

***

Arun George, 25, Nikhil NP, 25, Rashid K, 24, and Vimal Govind MK, 25, launched Genrobotics as a student startup in 2015, during their college days in MES College of Engineering, Kuttippuram, in Malappuram district, a nine-hour drive north of Thiruvananthapuram.

Working as part of the IEDC (the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Development Cell, about 400 of which have been set up by the Kerala Startup Mission, or KSM, to connect students with the ecosystem), they put together a first-generation (G1) powered exoskeleton, a wearable mobile machine, to help soldiers lift heavy weapons and military supplies in remote locations where automation wasn’t possible. While that created a buzz in the local media and was christened the Iron Man suit after their favourite superhero, the team fine-tuned the model next year and developed the G2 medical exoskeleton designed to help physically-challenged persons, like assisting amputees to walk. A paper on it won the best concept award at the International Conference on Mechatronics and Manufacturing held in Singapore in 2016.

But once they passed out of college, Genrobotics was chucked on to the backburner. There weren’t enough funds for their experiments and the quartet took up jobs with IT services companies, “just as any engineering graduate would do”, says Arun, now the chief administrative officer (CAO).

In times away from their day jobs, they would hop from one event to another to keep abreast of the latest innovations and opportunities in the field of robotics. In one such event organised in 2016 by KSM, the government’s nodal agency for startups, they met M Sivasankar, the IT secretary. “It was he who alerted us to the problem of manual scavenging and told us that the state was looking to mechanise the job,” says Arun.

Once the four staked out the extent of the problem, they figured it wasn’t a part-time job. Against the advice of their families and friends, they quit their well-paying corporate positions and, with a few lakhs of their savings, brought Genrobotics back on track. In June 2017, the company was formally registered and they approached KSM for funds. The KSM vetted their project and gave them a grant of ₹10 lakh, with which they roped in five of their classmates. The nine lived and worked out of a single room, barely slept and saved just about enough to pay for rent and food, channelling the rest towards R&D and production.

It was also around this time that the founding members met with A Shainamol, the then MD of the Kerala Water Authority (KWA), which is in charge of sewage cleaning in the state, to get details about the exact nature of the job. “They had earlier come up with the Iron Man suit so I knew they had ability. They spent hours with our engineers and even the sewer workers to ferret out details about the sizes of the manhole, the nature of the filth, etc,” says Shainamol. Accordingly, they made adaptations to accommodate the unique proportions of each manhole. For instance, controlled expansion of the leg to fit each space.

Shainamol also encouraged them to apply for an innovation grant given by the KWA. In January, Genrobotics was selected as the first Startup Innovator by the KWA and awarded ₹14 lakh with which they produced the beta version in just over a month.

At a time they were pinching pennies and reusing components from the Iron Man suit to refashion their cardboard prototype into a working product—it took anything between ₹10 lakh and ₹12 lakh to produce a Bandicoot—Anil Joshi, a managing partner with Unicorn India Ventures, caught the buzz around Genrobotics. He was introduced to their work during one of his visits to the state. Says Joshi, “Technology-wise, they have intelligently combined all details of mechanical, electro-mechanical, electronics, etc. Second, they have managed to build a world-class product without much intervention. In Genrobotics, we saw a promising team with a potential to take the company global.” Earlier this year, Unicorn swooped in with a close-to-$200,000 investment.

The single unit of the finished product is now with the Kerala Water Authority, which has ordered 50 more units in the next six months. In early June, Genrobotics will deliver its first order outside the state, to Tamil Nadu. It has received inquiries from the Cochin International Airport, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, the PMO and even from Sharjah.

Bandicoot’s ability to solve a large-scale India-first problem with a global solution has also drawn marquee investors towards it. Among them is Google India managing director and angel investor Rajan Anandan. “What they’ve done is technically very difficult. These robots have to be flexible, mimicking human behaviour. That’s got some serious tech stuff like computer vision which is hard. Also, you have to make it user-friendly. It has to be simpler than a smartphone. Imagine building something that is really really complex but its usability needs to be easier than a smartphone,” says Anandan.

Now that the orders are starting to come in, Genrobotics is gearing up for its next challenge: Setting up a manufacturing unit. At present, it is producing the components at various places, outsourcing some work, and assembling them at Kinfra (Kerala Industrial Infrastructure Development Corporation). But the team is scouting for an ideal location and sufficient capital to scale up production. Once that’s done, they expect the cost of production to come down considerably.

Anandan’s roadmap for the company over the next 6-12 months? Get product-market fit right based on the learnings from the robots deployed on the field, raise some capital, build a plant, crank out another couple of dozen units, and then get into large-scale business development, “because this is the kind of thing that you should sell to every municipality in the world”. “This can become a very large business, but it is very hard work,” he says.

There aren’t any Artificial Intelligence-enabled assistants strolling around, nor do any 3D holographic images hang mid-air; just a Transformer toy is seen sharing shelf space with a trophy, if you must identify a leitmotif. But beyond the mustard yellow walls and a slumping bean bag at the reception is a hub of activity where, inspired by the superhero, four 20-somethings are furiously racking their robotics savvy to take on a social scourge no less nefarious than any villain in the Marvel universe.

Just about a year old, Genrobotics scripted its headline act with Bandicoot, a 50-kg, pneumatic-powered, remote-controlled robot that goes down into a manhole, spreads its expandable limbs like a spider and scoops out the solid and liquid filth that block urban sewers. It has a robotic arm that, in a 360-degree motion, can sweep the floor of the manhole to collect the debris in a bucket, cleaning manholes in 20 minutes as opposed to over 2 hours that at least three workers would take to do it manually. Through its magnetic mechanism, it also lifts the heavy manhole cover on its own, a job earlier performed by multiple workers. Bandicoot ran its first successful trial in February, at the government medical college in Thiruvananthapuram, and later across the city before it was introduced to the state later that month by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan.

Just about a year old, Genrobotics scripted its headline act with Bandicoot, a 50-kg, pneumatic-powered, remote-controlled robot that goes down into a manhole, spreads its expandable limbs like a spider and scoops out the solid and liquid filth that block urban sewers. It has a robotic arm that, in a 360-degree motion, can sweep the floor of the manhole to collect the debris in a bucket, cleaning manholes in 20 minutes as opposed to over 2 hours that at least three workers would take to do it manually. Through its magnetic mechanism, it also lifts the heavy manhole cover on its own, a job earlier performed by multiple workers. Bandicoot ran its first successful trial in February, at the government medical college in Thiruvananthapuram, and later across the city before it was introduced to the state later that month by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan.By replicating all the human actions required to clean sewage, Bandicoot has provided a viable option to end the barbaric practice of manual scavenging in which sewage workers, mostly Dalits, are dipped into mucky manholes that often emit toxic gases and overflow with liquid sewage.

Despite being outlawed by the government—through the Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act, 1993, and Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, 2013—manual scavenging continues rampantly across the country due to lack of alternatives and casteism. According to IndiaSpend, a data journalism initiative, 102 workers reportedly died in 2017 while cleaning sewer lines manually. That’s an average of over eight deaths a month.

***

Arun George, 25, Nikhil NP, 25, Rashid K, 24, and Vimal Govind MK, 25, launched Genrobotics as a student startup in 2015, during their college days in MES College of Engineering, Kuttippuram, in Malappuram district, a nine-hour drive north of Thiruvananthapuram.

Working as part of the IEDC (the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Development Cell, about 400 of which have been set up by the Kerala Startup Mission, or KSM, to connect students with the ecosystem), they put together a first-generation (G1) powered exoskeleton, a wearable mobile machine, to help soldiers lift heavy weapons and military supplies in remote locations where automation wasn’t possible. While that created a buzz in the local media and was christened the Iron Man suit after their favourite superhero, the team fine-tuned the model next year and developed the G2 medical exoskeleton designed to help physically-challenged persons, like assisting amputees to walk. A paper on it won the best concept award at the International Conference on Mechatronics and Manufacturing held in Singapore in 2016.

But once they passed out of college, Genrobotics was chucked on to the backburner. There weren’t enough funds for their experiments and the quartet took up jobs with IT services companies, “just as any engineering graduate would do”, says Arun, now the chief administrative officer (CAO).

In times away from their day jobs, they would hop from one event to another to keep abreast of the latest innovations and opportunities in the field of robotics. In one such event organised in 2016 by KSM, the government’s nodal agency for startups, they met M Sivasankar, the IT secretary. “It was he who alerted us to the problem of manual scavenging and told us that the state was looking to mechanise the job,” says Arun.

Once the four staked out the extent of the problem, they figured it wasn’t a part-time job. Against the advice of their families and friends, they quit their well-paying corporate positions and, with a few lakhs of their savings, brought Genrobotics back on track. In June 2017, the company was formally registered and they approached KSM for funds. The KSM vetted their project and gave them a grant of ₹10 lakh, with which they roped in five of their classmates. The nine lived and worked out of a single room, barely slept and saved just about enough to pay for rent and food, channelling the rest towards R&D and production.

It was also around this time that the founding members met with A Shainamol, the then MD of the Kerala Water Authority (KWA), which is in charge of sewage cleaning in the state, to get details about the exact nature of the job. “They had earlier come up with the Iron Man suit so I knew they had ability. They spent hours with our engineers and even the sewer workers to ferret out details about the sizes of the manhole, the nature of the filth, etc,” says Shainamol. Accordingly, they made adaptations to accommodate the unique proportions of each manhole. For instance, controlled expansion of the leg to fit each space.

Shainamol also encouraged them to apply for an innovation grant given by the KWA. In January, Genrobotics was selected as the first Startup Innovator by the KWA and awarded ₹14 lakh with which they produced the beta version in just over a month.

At a time they were pinching pennies and reusing components from the Iron Man suit to refashion their cardboard prototype into a working product—it took anything between ₹10 lakh and ₹12 lakh to produce a Bandicoot—Anil Joshi, a managing partner with Unicorn India Ventures, caught the buzz around Genrobotics. He was introduced to their work during one of his visits to the state. Says Joshi, “Technology-wise, they have intelligently combined all details of mechanical, electro-mechanical, electronics, etc. Second, they have managed to build a world-class product without much intervention. In Genrobotics, we saw a promising team with a potential to take the company global.” Earlier this year, Unicorn swooped in with a close-to-$200,000 investment.

The single unit of the finished product is now with the Kerala Water Authority, which has ordered 50 more units in the next six months. In early June, Genrobotics will deliver its first order outside the state, to Tamil Nadu. It has received inquiries from the Cochin International Airport, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, the PMO and even from Sharjah.

Bandicoot’s ability to solve a large-scale India-first problem with a global solution has also drawn marquee investors towards it. Among them is Google India managing director and angel investor Rajan Anandan. “What they’ve done is technically very difficult. These robots have to be flexible, mimicking human behaviour. That’s got some serious tech stuff like computer vision which is hard. Also, you have to make it user-friendly. It has to be simpler than a smartphone. Imagine building something that is really really complex but its usability needs to be easier than a smartphone,” says Anandan.

Now that the orders are starting to come in, Genrobotics is gearing up for its next challenge: Setting up a manufacturing unit. At present, it is producing the components at various places, outsourcing some work, and assembling them at Kinfra (Kerala Industrial Infrastructure Development Corporation). But the team is scouting for an ideal location and sufficient capital to scale up production. Once that’s done, they expect the cost of production to come down considerably.

Anandan’s roadmap for the company over the next 6-12 months? Get product-market fit right based on the learnings from the robots deployed on the field, raise some capital, build a plant, crank out another couple of dozen units, and then get into large-scale business development, “because this is the kind of thing that you should sell to every municipality in the world”. “This can become a very large business, but it is very hard work,” he says.

Bandicoot is a 50-kg, pneumatic-powered, remote-controlled robot. Genrobotics has received enquiries from different states

Image: Vivek R Nair for Forbes India

Image: Vivek R Nair for Forbes India

Genrobotics is also looking to create a social impact, rehabilitating sewer workers who would have lost their jobs to automation. For this, it is training them in the use of Bandicoot and developing a simple user interface to help them navigate the controls smoothly. “We had to ensure this machine wouldn’t take away livelihoods,” says Arun.

Says Saji Gopinath, the CEO of the Kerala Startup Mission, “Conventionally, there was a belief that startups involved in hardware have a long gestation period before they can become successful, that the chances of success are low, that you require to burn a lot of money and a lot of resources to start with. These notions have been dispelled by the success story of Genrobotics.”

But, for Arun, the highest point in Genrobotics’s fledgling life lies somewhere else. The whole conversation around ending manual scavenging in the state, he says, began in 2016 when a vernacular daily published a telling image of a sewage worker dunked neck-deep in filth. It reached the CMO and chief minister Pinarayi Vijayan shot off a letter to the KWA and the IT secretary to find a solution on a war-footing. That set the ball rolling for a chain of events that culminated in late-February this year where Vijayan formally launched the Bandicoot. “That day, the robot was operated by the man whose picture had appeared in the newspaper. To see him transform from a sewer worker to an operator is our happiest moment yet,” says Arun.

Says Saji Gopinath, the CEO of the Kerala Startup Mission, “Conventionally, there was a belief that startups involved in hardware have a long gestation period before they can become successful, that the chances of success are low, that you require to burn a lot of money and a lot of resources to start with. These notions have been dispelled by the success story of Genrobotics.”

But, for Arun, the highest point in Genrobotics’s fledgling life lies somewhere else. The whole conversation around ending manual scavenging in the state, he says, began in 2016 when a vernacular daily published a telling image of a sewage worker dunked neck-deep in filth. It reached the CMO and chief minister Pinarayi Vijayan shot off a letter to the KWA and the IT secretary to find a solution on a war-footing. That set the ball rolling for a chain of events that culminated in late-February this year where Vijayan formally launched the Bandicoot. “That day, the robot was operated by the man whose picture had appeared in the newspaper. To see him transform from a sewer worker to an operator is our happiest moment yet,” says Arun.

X