- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- Big story: How will India vaccinate 1.3 billion people?

Big story: How will India vaccinate 1.3 billion people?

India is a powerhouse when it comes to vaccine manufacturing, but the focus is now on addressing the complexities in storing and distributing the Covid-19 vaccines

Pune-based Serum Institute of India has already stockpiled 40 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine

Photo courtesy: Serum Institute of India

The month of November brought some much-needed glimmer of hope in a rather painful year.

It all began with New York-based pharmaceutical giant Pfizer announcing that its vaccine candidate BNT162b2, developed in partnership with Mainz-based BioNTech, showed 90 percent effectiveness in preventing the coronavirus. A week later, 10-year-old pharmaceutical company Moderna announced that its coronavirus vaccine was 94.5 percent effective in preventing the virus. Moderna had given 15,000 participants their vaccine, of which only five developed Covid-19 with none of the five becoming severely ill.

The announcements were followed by claims from the Russian health ministry that its vaccine Sputnik-V showed 95 percent efficacy, while UK-based pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca announced that its vaccine, currently being manufactured in large doses at the Pune-based Serum Institute of India, showed up to 90 percent efficacy in preventing the virus. Two days later, AstraZeneca acknowledged an error in the manufacturing process, raising concerns about the efficacy.

Yet, despite AstraZeneca’s glitch, the recent announcements have managed to raise hopes about an end to a crisis that began in November last year. Globally, Covid-19 has affected some 60 million people, of which some 38.7 million have recovered so far. A recent spike, amidst talks of a second wave, has also meant that many European countries have begun locking down. India, which had announced a two-month lockdown in March this year, has emerged the second worst-hit country with over 9.6 million cases, and 8.6 million recoveries. The country’s death toll from the crisis stood at 1.3 lakh.

Now, with a surge in Covid-19 cases since November, soon after the festive season, India’s prime minister had in a meeting with the chief ministers of various state governments suggested that the immediate goal was to bring down positivity rate to about five percent. “Important issues related to progress of vaccine development, regulatory approvals and procurement were discussed,” Modi had tweeted soon after another review meeting with his administration on November 20. “Reviewed various issues like prioritisation of population groups, reaching out to HCWs, cold-chain infrastructure augmentation, adding vaccinators and tech platform for vaccine roll-out.”

But, even as the efficacy rates of the vaccines raise significant hope, it won’t be likely anytime this year that any of them will be made available in large numbers in India. On November 20, Pfizer had said that it was submitting a request to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of their mRNA vaccine candidate, which will potentially enable use of the vaccine in high-risk populations in the US by the middle to end of December 2020.

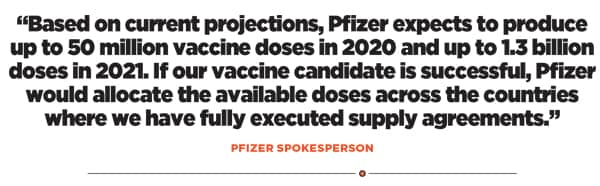

For India, however, Pfizer doesn’t have a definite timeline. “We remain committed to engaging with the Government of India to advance our dialogue and explore opportunities to make this vaccine available for use in the country,” a spokesperson for Pfizer told Forbes India. “Based on current projections, Pfizer expects to produce up to 50 million vaccine doses in 2020 and up to 1.3 billion doses in 2021. If our vaccine candidate is successful, Pfizer would allocate the available doses across the countries where we have fully executed supply agreements.”

Moderna is yet to respond to a questionnaire from Forbes India. “At this time, our priority is to ensure a rapid manufacturing and deployment of the vaccine to cater to a pandemic response scenario,” Pfizer added. “We are also mindful of the unique mRNA technology that is being utilised in this vaccine. Given these considerations, Pfizer has created two dedicated supply lines with established vaccine capabilities–one each in US and Europe–to exclusively manufacture this vaccine for use across the world.”

That means, it is quite likely that the country’s indigenous manufacturers will have some critical role to play in the coming months, apart from a need to ramp up storage and distribution capacity to make the most of our manufacturing capabilities.

A November report by US-based Duke University’s Global Health Innovation Center reckons that India has already laid out plans to procure enough vaccines to cover nearly half of the country’s population. “Among middle-income countries, the Launch and Scale data show that Brazil and India—each of which have large vaccine manufacturing infrastructure—already have secured the rights to enough vaccines to cover about half of their populations and are negotiating additional deals,” a statement from the Center says.

All Eyes on Indigenous Manufacturers

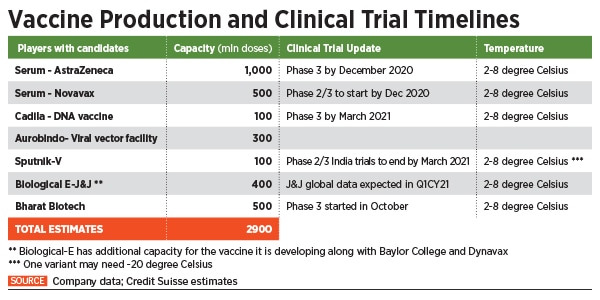

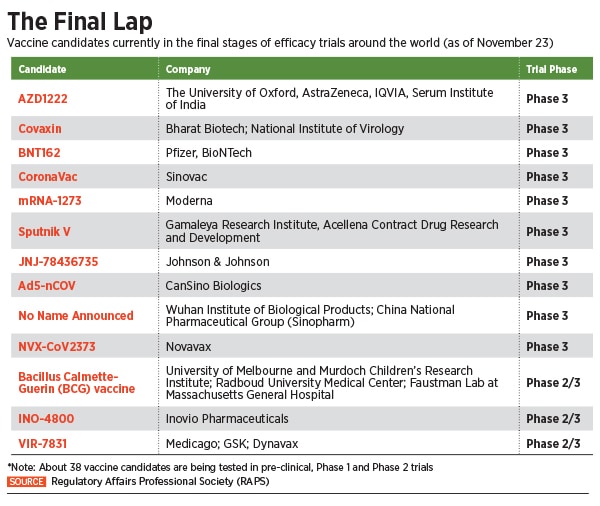

India currently has about seven pharmaceutical companies looking to develop or manufacture a vaccine for large-scale deployment, as soon as they receive approvals. Out of this, candidates of four ventures have reached late-stage trials.

The latter include the Pune-based Serum Institute of India, the world’s largest vaccine maker by volume. Of this, Adar Poonawalla-led SII has already stockpiled some 40 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, according to a spokesperson. Hyderabad-based Dr Reddy’s Laboratories is currently conducting Phase 2 / 3 trials of the Russian Sputnik-V vaccine and has already secured the purchase of as many as 100 million doses of the vaccine.

On November 27, an agreement was also signed between the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) and Hyderabad-based Hetero Biopharma to manufacture over 100 million doses a year of Russia’s coronavirus disease (Covid-19) vaccine Sputnik-V beginning 2021.

Another frontrunner in the vaccine race is Bharat Biotech, which is developing Covaxin, India’s first indigenous Covid-19 vaccine candidate, in collaboration with the National Institute of Virology and the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). On November 16, the Hyderabad-based company announced the launch of Phase 3 trials for the vaccine with 26,000 volunteers across 25 centres in India. According to the company, it is the largest clinical trial conducted for a Covid-19 vaccine in India so far.

“We are working towards manufacturing at least 150 million doses [currently] and with expansion into our new facilities, aiming towards 500 million doses by the end of 2021,” Sai Prasad, executive director, Bharat Biotech International Limited (BBIL), told Forbes India. “Currently, BBIL has invested Rs350-400 crore towards the development of Covaxin alone, which includes vaccine development, manufacturing scale-up, trials and loss of sales towards existing vaccines so as to better concentrate on the Covid-19 vaccines.”

Apart from Covaxin, Bharat Biotech has also placed its bets on two other vaccines. One is the CoroFlu, a one-drop Covid-19 nasal vaccine, which is being developed in collaboration with virologists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and vaccine company FluGen. “We are also working on another intranasal vaccine candidate in collaboration with the Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, which is also in pre-clinical development. We will soon apply for Phase 1 approval,” Prasad adds.

Another Hyderabad-based company Biological E is manufacturing the viral vector vaccine being developed by Johnson & Johnson (currently in Phase 3 trials), while its own vaccine candidate being developed along with Houston-based Baylor College and US biopharma company Dynavax is in Phase 1 / 2 of trials and is getting ready for Phase 3 trials with about 30,000 people in the first quarter of 2021. The company is also in late stage talks for a potential vaccine candidate using an mRNA platform.

“The advantage that the mRNA platform provides is that it can be scaled up very fast,” says Vishal Manchanda, research analyst for pharma at Nirmal Bang Institutional Equities Research. “It is far easier to manufacture and that means even with a single plant, you can manufacture enough.”

How much will India get?

In an interview with the Financial Times in September, Poonawalla had said that it may take us at least 15 billion doses and five more years to make enough vaccines to cover the world’s population. And the rich countries are already hedging their bets to procure as many doses as possible, even before any vaccine candidates are approved for the market.

In a show of ‘vaccine nationalism’, the US government’s Operation Warp Speed has promised Pfizer $1.95 billion for 100 million doses, which means the company’s entire 50 million dose capacity for 2020 and about half of its projected production for next year. Similarly, Moderna has received $1.5 billion for 100 million doses from the US government, which includes 20 million doses by the end of 2020. According to a report in The New York Times, the US government has awarded over $10 billion to seven different companies to develop vaccines for the country.

Similarly, according to the BBC, the UK government has signed deals with six leading vaccine manufacturers, including J&J, Novavax, Pfizer and AstraZeneca. If their candidates become successful, the UK will have a stockpile of 340 million doses of coronavirus vaccines for a population of 68 million people, which means roughly five doses per citizen.

Similarly, according to the BBC, the UK government has signed deals with six leading vaccine manufacturers, including J&J, Novavax, Pfizer and AstraZeneca. If their candidates become successful, the UK will have a stockpile of 340 million doses of coronavirus vaccines for a population of 68 million people, which means roughly five doses per citizen.

In India, Union health minister Dr Harsh Vardhan announced on October 4 that India expects to immunise about 20-25 crore people by August 2021---about a sixth of the total population---with about 500 million doses. In August, the Centre formed the National Expert Group of Vaccine Administration for Covid-19 (NEGVAC) chaired by Niti Aayog member VK Paul. The expert group, apart from discussing financial resources required for procuring the vaccine, is also looking into delivery platforms like cold chain and associated infrastructure required to roll out the Covid-19 vaccines.

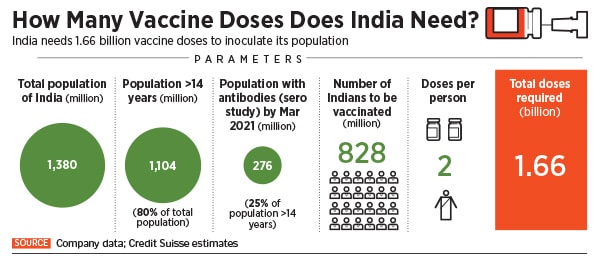

A November 2020 report from Credit Suisse says that India will need about 1.7 billion Covid-19 vaccine doses to vaccinate majority of its adult population. “It targets to administer 400-500 million doses by July-2021,” the report says. “In our view, there is sufficient capacity for vaccine manufacturing (>2.4 bn doses) and various components like vials, stoppers, syringes, gauze, alcohol swabs, etc.”

With manufacturing capacity in itself not being much of a concern, experts are now turning their focus to the complexity associated with storing and distributing the vaccine, which largely limits the number of vaccines that can be administered at a time to around 500-600 million.

“The rollout has to be prioritised and planned in a systematic manner. Doctors and health care workers getting directly exposed to the virus have to be covered first, followed by other frontline personnel like police and sanitary workers,” says E Sreekumar, a senior scientist at the Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology. He says the government has already started taking count of the number of first responders across the country to take stock of the rollout situation.

Mahima Datla, managing director of Biological E, says that India already has a good primary vaccination system. She is referring to the country’s 42-year-old successful universal immunization programme (UIP) that reaches about 26 million newborns and 30 million pregnant women every year with close to 600 million doses of vaccines every year. According to the Immunisation division under the National Health Mission (NHM) of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India has 27,000 cold chain centres and 76,000 cold chain equipment to store vaccines for immunisation.

Making space for Covid-19, however, would strain this capacity. Datla points out that the Covid-19 vaccine will have to be administered to a larger and more diverse population, including the elderly and people with co-morbidities. Handling an immunisation programme of this scale, therefore, is a first for India. A stronger infrastructure that can track and trace dosages administered to people is essential, she says. “Most Covid vaccine candidates have to be administered over two doses, so we need to put together an infrastructure and a strategy on how to execute this.”

And that may not come easy, especially from the private sector. “What happens to all these storage facilities once the ongoing situation is over?” asks Arif Siddiqui, the founder and CEO of Mumbai-based Coign Consulting, a logistics consultancy firm. “We are a country where cold storage facilities are yet to reach many small towns. If you want to build up storage facilities that meet good manufacturing practices, the private sector may not see much economic sense in that. The government will have to set up the infrastructure. Another area of concern is transportation, and the question is how equipped are we on that front?”

With India’s current facilities, Credit Suisse reckons that the country will be able to administer only between 550 million and 600 million doses of vaccine annually. “The bottleneck in India’s Covid-19 play will be cold storage infrastructure (especially refrigerated vans) and by using a part of the capacity of current immunization program (600 million doses) and the cold chain infrastructure of the private sector (250-300mn doses), potential vaccinations can reach 550-600 million doses annually,” the Credit Suisse report says. That will also require a manpower of around 100,000.

Most Covid-19 vaccines, including the ones being rolled out by Bharat Biotech and Serum Institute, are to be stored at temperatures between 2 and 8 degree Celsius, while some others like the ones being developed by Moderna and Pfizer need to be stored at sub-zero temperatures of -20 degree and -70 degree Celsius respectively.

Apollo, India’s largest private hospital chain, is ramping up its distribution capacity to be able to serve 1 million vaccine doses a day through its 500 corporate health centres, 70 hospitals, 400-plus clinics and 19 medicine-supply hubs with cold chain facilities.

“Our sister company Keimed operates about 19 warehouses that can reach 80 percent of India in 48 hours because they distribute to an additional 35,000 pharmacies and 800 hospitals,” says Shobana Kamineni, executive vice-chairperson, Apollo Hospitals Group, adding that they have identified 17,000 people within the group who are certified to administer the vaccine.

According to a list on the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO) website under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India has about 22 licensed vaccine manufacturing sites in India, among the most in the world. Kamineni reiterates that India has been manufacturing 60 percent of the world’s vaccines, and with Covid-19, the country has also progressed on the research and development front.

From a distribution standpoint, she believes that while India’s cold chain facilities are well-placed for vaccines requiring 2-8 degree Celsius, storage of ones that require sub-zero temperatures, like the ones being developed by Moderna and Pfizer, will be “a challenge”. Building and maintaining a cold chain, she says, requires investments between Rs30 crore and Rs70 crore.

Sreekumar calls for the need for surveillance and gathering data about vaccine administration, explaining that unless the community feels the urgent need to get vaccinated---which he believes is waning as people feel they will get better even without a vaccine in most cases---people’s enthusiasm in general towards the vaccine is likely to come down with time and the turnout for vaccination campaigns would reduce as a result.

Datla suggests that perhaps an Aadhaar-linked database could be used to track immunisation, and that implementing this at scale would be a phenomenal achievement. “I think there’s a huge role for India’s IT talent to get deployed into this.”

Clarity Awaited

The government's universal immunisation programme geared toward maternal and child vaccination has a capacity to store about 600 million doses annually in India. Out of this, only 200-250 million capacity is likely to be available for Covid-19 vaccines.

Photo: Satish Bate/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

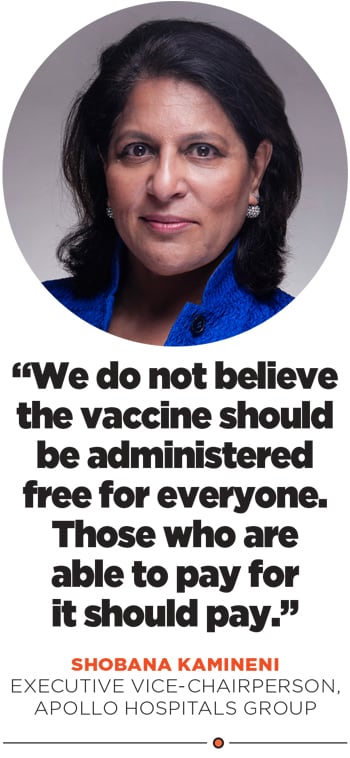

For now, however, Kamineni suggests that private sector stakeholders are waiting for clarity on two fronts. First, they are unsure whether the vaccines will be procured directly by the government or whether they will be allowed to buy, and second is around pricing. “We do not believe the vaccine should be administered free for everyone and those who are able to pay for it should pay,” she says.

Datla of Biological E says that it will be counterproductive if a vaccine candidate is less immunogenic or more expensive, to which Sreekumar adds that it is important for companies to never lose sight of or compromise on safety during clinical trials.

Bharat Biotech, for example, had an adverse event during Phase 1 trials in August, where a 35-year-old participant with no co-morbidities was hospitalised with viral pneumonitis a few days after being administered a Covaxin dose. Globally, AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson had temporarily halted their Phase 3 trials after an adverse event was observed in their respective trial candidates.

Bharat Biotech said in a statement that the adverse event was reported to the regulators within 24 hours of its occurrence and confirmation. “The adverse event was investigated thoroughly and determined as not vaccine related,” the statement said. Prasad, referring to the efficacy outcome goals they are trying to maintain for the trials, told Forbes India they are “optimistic for good efficacy outcomes” and “confident in the time-tested safety of the inactivated vaccine platform”.

Sreekumar points out that not much data is being made available regularly about the safety levels of the vaccines under trial. “Efficacy has to be measured under various parameters, like the kind of immune response required for protection, how long the antibody response is going to sustain, whether we just need antibodies or other kinds of immune response etc. Unless all these questions are answered, and sufficient, transparent data is provided in the public domain, we’ll not be in a very safe position to proclaim that a vaccine is going to be a panacea for anything and everything related to Covid-19.”

He argues that it is important to keep up alternative treatment strategies like repurposing antiviral drugs including Favipiravir (flu), Ivermectin (anti-parasitic) and Tocilizumab (for rheumatoid arthritis) that are currently being used in the absence of a vaccine. “Clinicians have become more experienced compared to six months ago, our diagnostic systems have become faster and the number of people who need invasive intervention for Covid-19 is coming down,” he says. “So in a scenario where a vaccine might not be available immediately for everyone, we must continue building treatment schedules around antivirals.”

That’s something even companies such as Dr Reddy’s have been betting on. The Hyderabad-based company has built up a portfolio over the past few months to address the various stages of illness caused by the coronavirus. In September, Dr Reddy’s announced the launch of Remdesivir under the brand name Redyx in India and got exclusive rights to make, sell and distribute Avigan (Favipiravir) 200 mg tablets in India for patients with mild-to-moderate symptoms.

As vaccine roll-outs for India get tentatively expected around early –to-mid next year, experts also remind that vaccines generally take between 10 and 20 years to be developed, and if a Covid-19 vaccine is being made available within a year’s time, it is due to highly fast-tracked processes. “If it is going well, everyone will accept it, but one adverse event and the credibility that has been generated will be shattered, which will then affect people’s confidence in other vaccines too,” says Sreekumar. “So, ensuring safety before rollouts is paramount.”