Can wildfires be prevented in a world dealing with climate change?

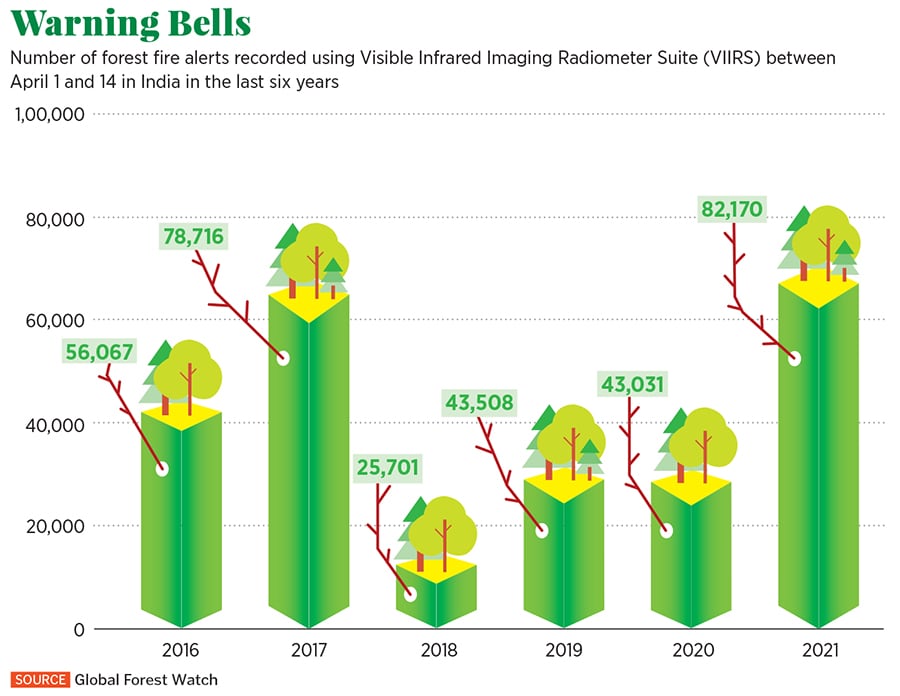

India recorded 82,170 forest fire alerts from April 1 to 14, nearly doubling from 43,031 in the same period in 2020. Forest fires, wildfires and their alerts in the country have gone up sharply in recent times, posing a serious threat to our environment, wildlife and biodiversity

Firefighters and forest officials struggled to control fires in the Similipal Biosphere Reserve, about 200 km away from Bhubaneswar, Odisha, earlier this year

Firefighters and forest officials struggled to control fires in the Similipal Biosphere Reserve, about 200 km away from Bhubaneswar, Odisha, earlier this year

Image: STR/NurPhoto via Getty Images

With her arms stretched wide, a content smile on her lips and moist eyes, an Indian Forest Service (IFS) officer looked up and thanked the pouring skies in March. Her little dance of joy in the rain-washed jungle went viral on social media. There was reason for her to turn emotional.

For weeks, the woman, along with others, had been battling raging forest fires in Similipal’s 2,750 sq km area in Odisha. The wildfire at the Unesco World Heritage biodiversity hotspot and Asia’s largest biosphere was uncontrollable even with 1,000 combatants. The devastation was heartbreaking: The sky had turned reddish orange, filled with rings of bright fire, threatening the biodiversity, wildlife and locals there. The unexpected rain and thunderstorms, understandably, brought relief.

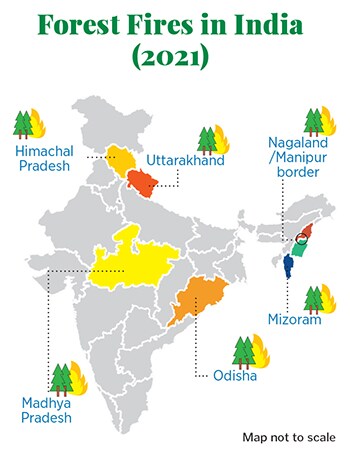

India recorded 82,170 forest fire alerts from April 1 to 14, nearly doubling from 43,031 in the same period in 2020, according to Global Forest Watch, an open-source monitoring application. Most were concentrated in North and Central India—Odisha, Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Jharkhand and Telangana. The Forest Survey of India (FSI) also reported a consistent increase in fires in the country: From 8,654 in 2004 to 35,888 in 2017. It found 277,758 forest fire points—20,862 in Assam; 25,995 in Chhattisgarh; 24,422 in Madhya Pradesh; 20,686 in Maharashtra; 32,659 in Mizoram and 26,719 in Odisha.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Arun Lohra and his family collecting dry leaves from Tisiya Forest

Arun Lohra and his family collecting dry leaves from Tisiya Forest