C-Camp: India's effort to back biotech startups begins to bear fruit

What's needed now is the infrastructure, and a venture capital and private equity network for the next critical phase of growth

One of the labs in the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Platforms (C-Camp)

One of the labs in the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Platforms (C-Camp)

More than a decade ago, with the backing of Government of India’s Department of Biotechnology, an effort began to encourage biotech research in the country with the aim of bringing life-sciences-based products to the market that could potentially benefit millions of people.

With the progress made by some of these startups–even as the venture ecosystem in India expanded – that effort is today beginning to attract a small number of investors, both local and foreign. This increases the chances that Indian biotech startups, which largely relied on government grants and small amounts of seed money, can now increasingly look to private venture capital (VC) for more significant funding.

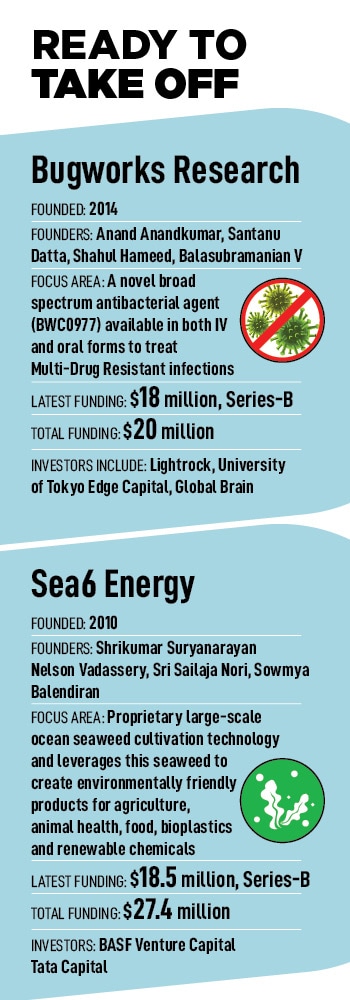

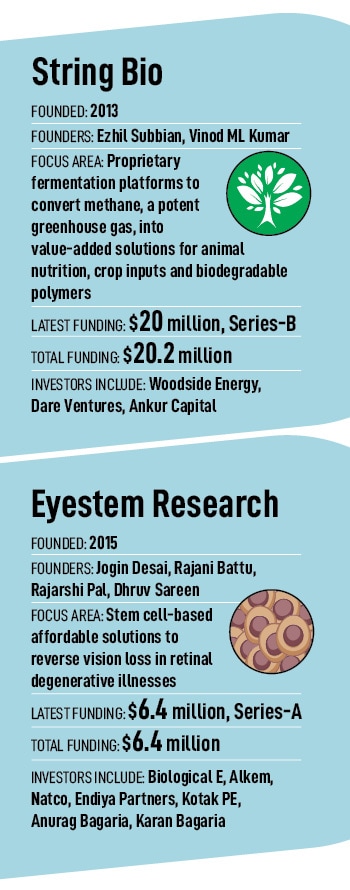

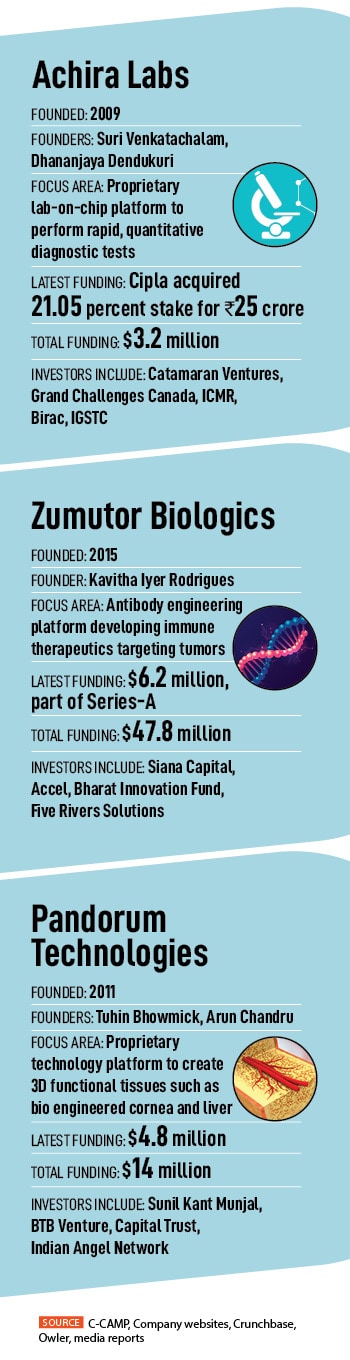

To underscore that point, the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Platforms (C-Camp) recently announced that seven biotech startups started with its support have together raised about $70 million this year, at a collective valuation of about $250 million.

Those are small numbers, in comparison with the billions that global investors have poured into India’s ecommerce sector, for example, but that these ventures have been able to raise tens of millions of dollars at Series-A and Series-B stages reflects the growing investor interest in supporting deep-science ventures out of India.

C-Camp—co-located with the National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bengaluru—is one of India’s biggest government-backed biotech startup enablers. It was conceptualised to provide office space, lab infrastructure, including expensive sophisticated equipment, as a service, and business handholding and networking. The organisation has supported hundreds of biotech startups so far.

“It might appear to be impossible, when something is just an idea, but these startups are showing that there can be significant outcomes,” says Taslimarif Saiyed, CEO and director of C-Camp.

“It might appear to be impossible, when something is just an idea, but these startups are showing that there can be significant outcomes,” says Taslimarif Saiyed, CEO and director of C-Camp.

In general, a handful of early-stage VC firms, like Endiya Partners, Inflexor Ventures, and Speciale Invest are doing significant work in backing deep-tech startups in India. But the next stage of funding is missing.

In general, a handful of early-stage VC firms, like Endiya Partners, Inflexor Ventures, and Speciale Invest are doing significant work in backing deep-tech startups in India. But the next stage of funding is missing. “This year, we hope to do $8-10 million in revenue, just based on this product,” says Suryanarayan, who was also one of the architects of C-Camp. In fact, he was also involved in recruiting Saiyed to lead C-Camp. Saiyed, at the time, was looking to come back to India from the US, where he was working on post-doctoral research—a winner of the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation fellowship—as well as biotech venture consulting at University of California San Francisco.

“This year, we hope to do $8-10 million in revenue, just based on this product,” says Suryanarayan, who was also one of the architects of C-Camp. In fact, he was also involved in recruiting Saiyed to lead C-Camp. Saiyed, at the time, was looking to come back to India from the US, where he was working on post-doctoral research—a winner of the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation fellowship—as well as biotech venture consulting at University of California San Francisco.