Data Protection Bill: Can it ensure your privacy online?

Following WhatsApp's proposed changes to its privacy policy, all eyes are now on the Bill that will be tabled in Parliament in February. But is the Bill robust enough?

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

The internet, in a post Covid-19 world, has brought us together in a way that it had not in the past. We are doing our jobs online, meeting people online, buying and selling online, and spending more of our lives online.

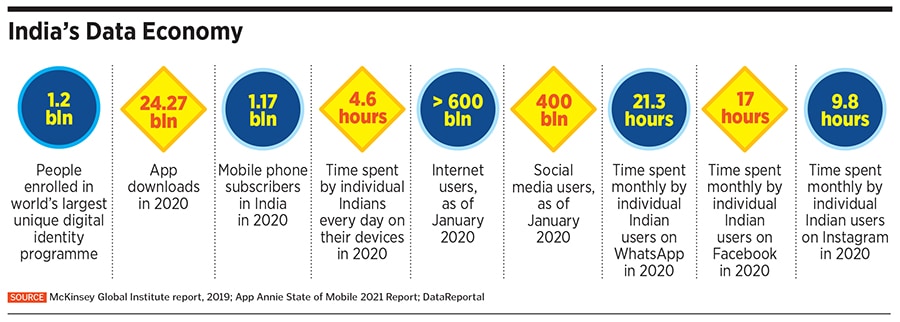

The State of Mobile 2021 report by App Annie, a mobile analytics firm, shows that Indians spent more than 650 million hours using mobile applications in 2020. During that time, consumer spending through apps hit $500 million (Rs 3,652 crore). There were over 24 billion mobile app downloads, and people spent the maximum time on WhatsApp. Every Indian spent more than 21 hours a month on the app, followed by 17 hours on its parent company Facebook, and 9.8 hours on Instagram, also owned by Facebook.

Earlier in January, WhatsApp—it has 400 million users in India—announced policy updates, in which a closer integration with Facebook would result in sharing of private user chat data with advertisers. This has made the need for a legislative framework to empower users against the misuse of personal information more crucial than ever.

Earlier in January, WhatsApp—it has 400 million users in India—announced policy updates, in which a closer integration with Facebook would result in sharing of private user chat data with advertisers. This has made the need for a legislative framework to empower users against the misuse of personal information more crucial than ever.

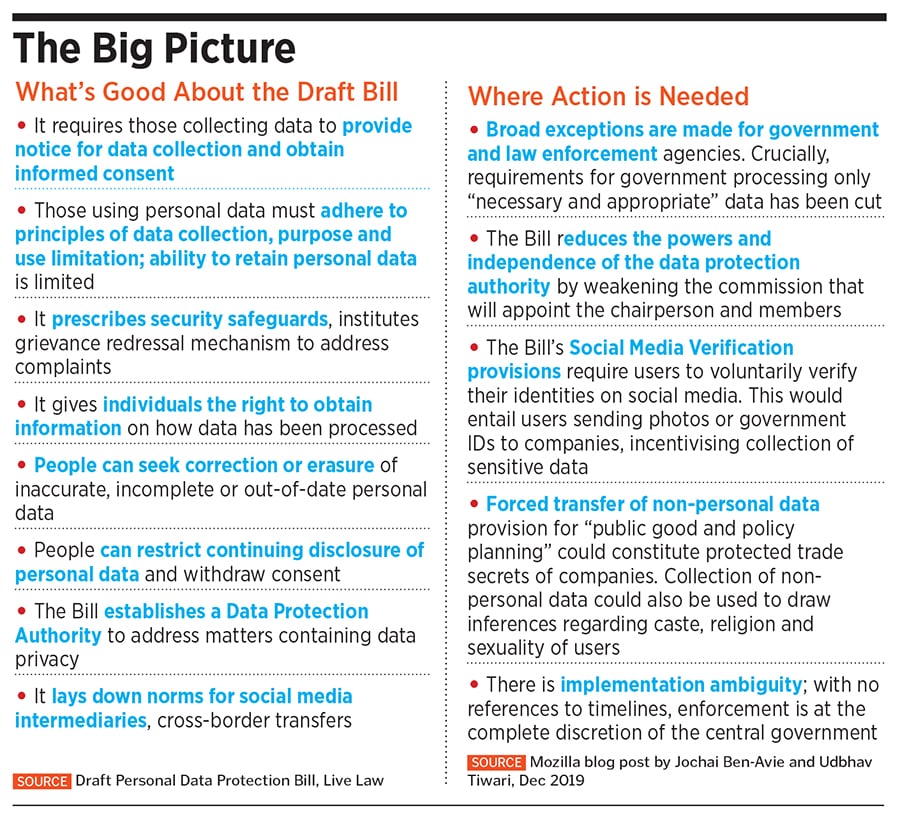

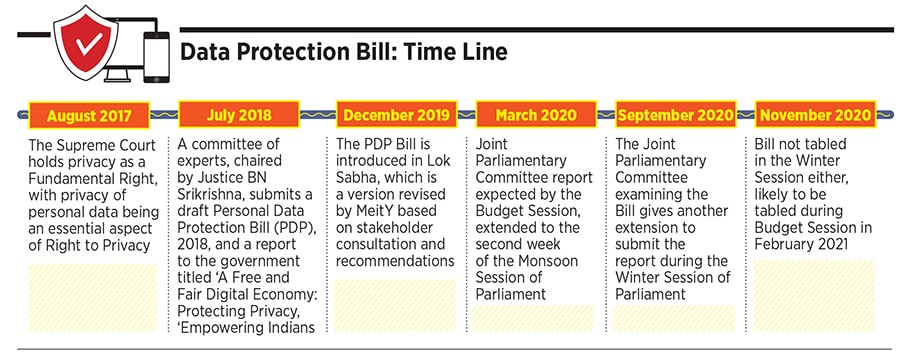

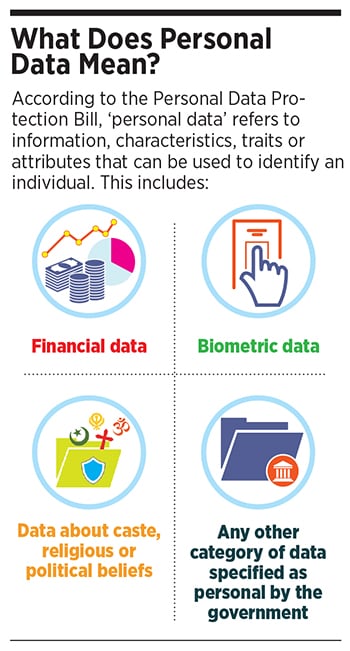

Although WhatsApp has subsequently postponed the rollout of its new privacy policy to May 15 for users to review and accept the new terms, all eyes are on the Budget session of the Parliament in February, where a Joint Parliamentary Committee is expected to table its report on the draft Personal Data Protection (PDP) Bill, 2019. The Bill is a result of the Supreme Court declaring privacy as a Fundamental Right in 2017, and it not only has provisions for individual consent and control over private online data, but also outlines strong obligations for companies that use and process this data.

“Had there been a data regulator during the WhatsApp privacy policy debate, it would have assessed if the policy meets data minimisation and purpose limitation requirements, and would have come out with a review immediately,” says Kazim Rizvi, founder of The Dialogue, a technology public policy think-tank. According to him, given that Indians are sharing more personal data online, transacting more through digital platforms, and depending more on internet service providers to go about their daily life than ever before, there need to be checks and balances around data collection and processing practices, in which both technology companies and the state are held accountable.