Delivery and revenge dining: How Riyaaz Amlani survived the Covid-19 battering

The restaurateur wouldn't have imagined that he would mark 20 years in F&B by devising a playbook from scratch. But he's weathered the Covid storm and is looking set to return to his growth trajectory

Riyaaz Amlani, CEO and MD of Impresario Handmade Restaurants, at Carter Road Social; Image: Neha Mithbawker

Riyaaz Amlani, CEO and MD of Impresario Handmade Restaurants, at Carter Road Social; Image: Neha Mithbawker

On a hot weekday afternoon in March, the Carter Road outlet of Social is packed to its Covid-mandated capacity. Waiters shuttle briskly between the kitchen and the tables, while the clink and jingle of the cocktail-shaker gives away the beverage orders pouring in. As he surveys one of his most popular hangouts, you can tell that the ever-affable Riyaaz Amlani, CEO and MD of Impresario Handmade Restaurants, is beaming behind his mask. “We are back to 85 percent of our pre-Covid levels. I can feel a boom coming up,” says the 46-year-old restaurateur, who runs 13 brands, including the likes of Social, Soufflé I S'il Vous Plaît, Slink & Bardot, Smoke House Deli and Ishaara. “Once the vaccines roll out, people will want to step out with a vengeance.”

This is where the redoubtable Mr Murphy must have had a quiet laugh, for, within days, cases began to surge, and a second, far more lethal Covid wave began to sweep the nation—patients mounted to lakhs daily, with a peak of 4 lakh-plus on May 6, and several states began to reel under a shortage of oxygen and hospital beds. In the middle of the unfolding calamity, restaurants were ordered to shut for a second time, and months of zero-income from dine-in returned.

We speak to Amlani again, this time over a Zoom call from Dubai, once the second wave ebbs. But medical circles are already abuzz with the possibility of a third wave, albeit less virulent, and the sword of subsequent lockdowns hang over a crippled F&B industry. However, Amlani sounds upbeat while speaking about his prospects. “The subsequent waves will peter out at some point. The future of the business remains bright because the urge to socialise is a permanent one,” he says. “Besides, while we don’t know when the third wave will come, we now have the playbook for business during shutdowns.”

In 2021, Amlani completed 20 years in the F&B business, having incorporated Impresario in 2001 and kickstarting his venture next year with Mocha, the ebullient coffee shop on Mumbai’s Churchgate Street, styled on Moroccan quahveh khannes. En route, he also created fine-dining restaurant Salt Water Grill, hangouts Salt Water Cafe and Smoke House Deli, and, in 2014, the ubiquitous Social that, by early 2020, clocked 26 outlets across six cities. Before the pandemic, Amlani’s company recorded a business growth at 25 percent CAGR, logged a revenue run rate of Rs 480 crore, and had a network of 58 restaurants, cafes and bars across 16 cities. In March 2020, Covid flattened it like every other neighbourhood diner struggling to figure out where its next penny would come from.

In 2021, Amlani completed 20 years in the F&B business, having incorporated Impresario in 2001 and kickstarting his venture next year with Mocha, the ebullient coffee shop on Mumbai’s Churchgate Street, styled on Moroccan quahveh khannes. En route, he also created fine-dining restaurant Salt Water Grill, hangouts Salt Water Cafe and Smoke House Deli, and, in 2014, the ubiquitous Social that, by early 2020, clocked 26 outlets across six cities. Before the pandemic, Amlani’s company recorded a business growth at 25 percent CAGR, logged a revenue run rate of Rs 480 crore, and had a network of 58 restaurants, cafes and bars across 16 cities. In March 2020, Covid flattened it like every other neighbourhood diner struggling to figure out where its next penny would come from.

“When Covid struck, we realised how lopsided our business was towards dine-in. In those months, we turned our focus to delivery. We had been doing it earlier as well, but through aggregator platforms and our own fleet. But with no income for months, we built delivery-only brands and focussed on developing a direct-to-customer tech interface that would save us the commissions we would have to pay the aggregator platforms,” says Amlani.

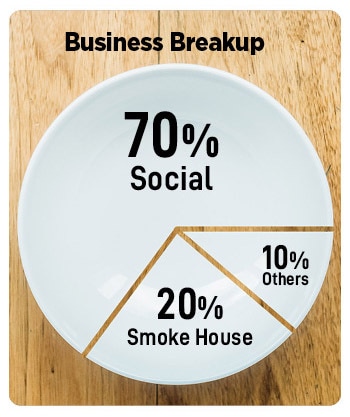

With Social, Impresario found the sweet spot that had been amiss in both Mocha and Salt Water. “Our APCs were Rs 900-plus, way higher than Mocha, and we had 5x table turnarounds than Saltwater,” says Amlani. It also offers the biggest returns on investment for Impresario, bringing in 70 percent of the business for the group, and breaks even in 18 months—“QSRs usually take four and a half years,” says Amlani. Smoke House Deli is the next-best performer with 20 percent of the business and a breakeven period of two and a half years.

With Social, Impresario found the sweet spot that had been amiss in both Mocha and Salt Water. “Our APCs were Rs 900-plus, way higher than Mocha, and we had 5x table turnarounds than Saltwater,” says Amlani. It also offers the biggest returns on investment for Impresario, bringing in 70 percent of the business for the group, and breaks even in 18 months—“QSRs usually take four and a half years,” says Amlani. Smoke House Deli is the next-best performer with 20 percent of the business and a breakeven period of two and a half years.