Fighting Superbugs: How an Indian Avenger is building a life-saving weapon

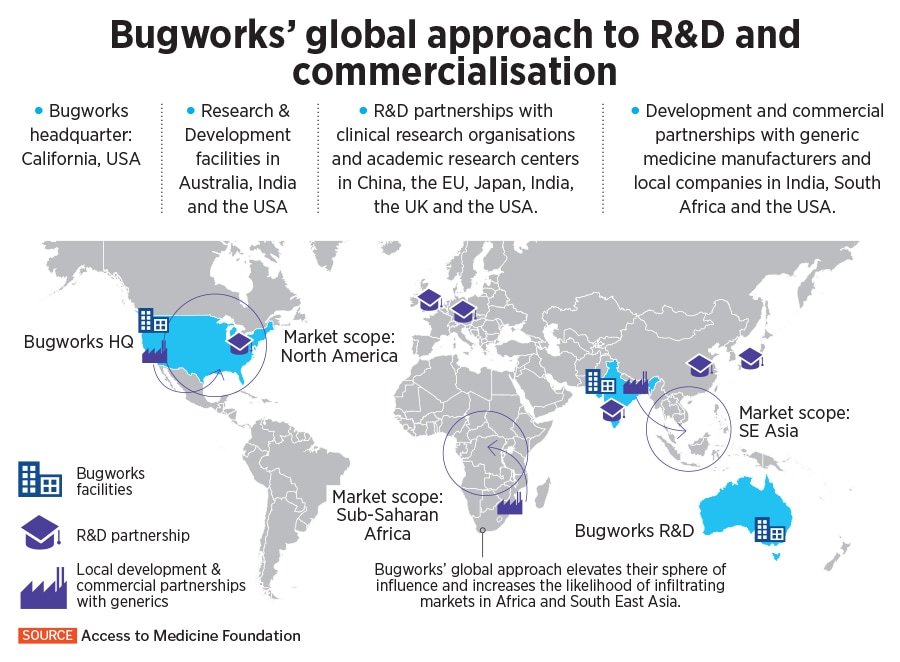

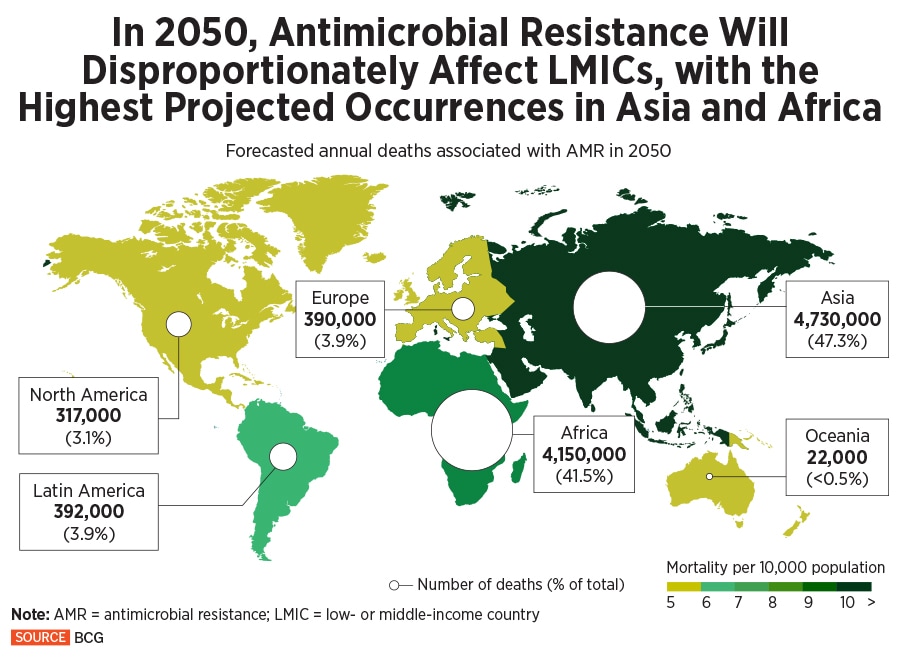

Big pharma has little interest in antibiotics because there's not enough money in it, making Bugworks, with its R&D in India, among a handful of startups that is attempting the impossible

Left to right: Shahul Hameed, Santanu Datta, Anand Anandkumar, and Balasubramaniam V - Bugworks Reasearch cofounders.

Photo credits: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Left to right: Shahul Hameed, Santanu Datta, Anand Anandkumar, and Balasubramaniam V - Bugworks Reasearch cofounders.

Photo credits: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Anandkumar’s journey to founding his drug discovery company, Bugworks, out of India and the US, is a long one, and it started in an entirely different industry. Over the last six months or so, however, Anandkumar and his co-founders Santanu Datta, Shahul Hameed and Balasubramanian V, have been engaged in the first significant step towards making a new broad-spectrum antibiotic that might kill bacteria already resistant to other antibiotics and medicines. If they succeed, it will be the first time in more than 60 years that a new class of antibiotics will come to the market to combat ‘superbugs.’ And it will also be a significant milestone for drug discovery out of India. Since November, Bugworks has been putting its first promising candidate, a molecule the founders have named BWC0977, through the first phase of clinical trials. The tests are being conducted in Australia. If all goes well, then, by around October this year, they will be ready to move into Phase 2 trials. An eventual commercial drug, even if everything goes well and according to plan, is still at least 3-4 years away. But if it does come to the market, then Bugworks’ founders expect it to be able to combat bacteria that cause severe urinary tract infections, but also, eventually, pneumonia and infections of the bloodstream, kidney, stomach, skin and so on.