Fund managers worry as Sebi tightens noose around AIF Investment Committees

While a few managers believe this will bring in more accountability, others express concern that regulatory hurdles might deter independent experts from accepting IC roles

Image: Shutterstock

Image: ShutterstockIt was an easy day for Malini Sharma (name changed) who is an external advisor and investment committee member to private equity funds in India. But in the evening of October 19, a circular on the website of markets regulator Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) brought in a series of amendments to the Alternative Investment Funds (AIF) Regulations of 2012. This is not unusual, but of late, Sebi is on a spree of dropping circulars after circulars on AIF guidelines, and tightening the noose around this largely independent sector that is usually less-understood among the common folk.

Sharma, however, is not common folk. A private equity investor for the last two decades, she sits on the boards of some of the largest homegrown funds in India. Yet, she is worried. To know why, we have to first understand how Indian PE funds work.

PE and venture capital funds in India register themselves as AIFs and are governed by AIFs regulations that came into effect in 2012 after Sebi repealed the Venture Capital Fund (VCF) regulation of 1996.

Fund managers have to raise a minimum of Rs1 crore from each investor and they cannot have more 1000 investors in each fund. Sebi has specified that fund managers, as part of their skin the game, have to invest 2.5 percent of the fund value or $1 million, whichever is lower. But Sebi did not specify the rules for internal fund structure or for penalising members in the fund.

Globally, PE and VC funds usually have very lean teams and they constitute a committee called the investment committee (IC), comprising the decision-makers of the fund, experienced professionals and marquee names from the industry. In most fund constructs, the IC has a final say on whether a fund manager should go ahead with the deal or not. Almost all homegrown Indian funds follow this structure.

The Sebi circular released on October 19 firstly stated that the fund manager shall be responsible for investment decisions of the AIFs. Usually, the investment manager is the name of the firm under which the fund is registered, and the firm was liable for any cases against them, and not individuals.

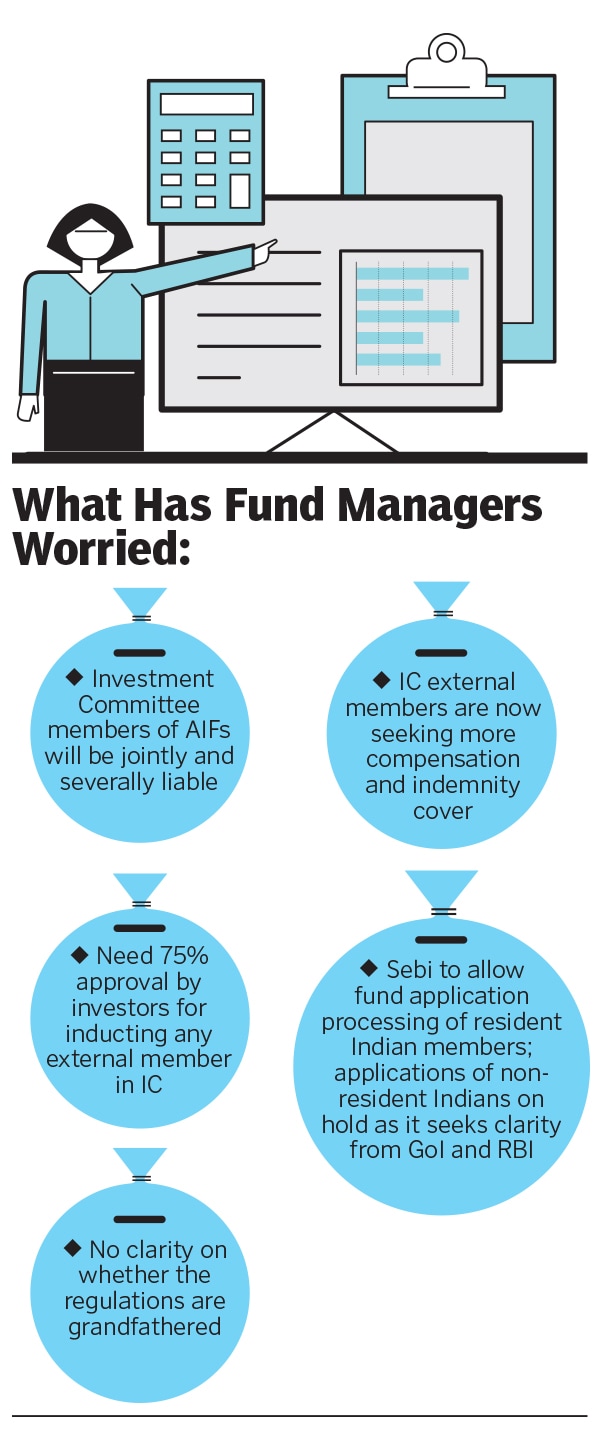

The second part, which has the likes of Sharma worried, is where Sebi states that the members of the IC shall be equally (jointly and personally) responsible as the fund manager for investment decisions. This is the first time the Sebi has referred to the IC since 2012.

Sharma says, “Our job is predominantly to oversee if the deal that the fund manager has brought is a good deal or not on an economic and financial basis. But this circular says that we will be personally and severally responsible for everything that the fund does apart from just investing. I would go bankrupt if I have to defend myself in the large funds that I serve, and it is a genuine concern for everyone in the ecosystem.”

The IC is usually concerned about the financials and the economic viability of the deal. The rest of the cleaning in terms of corporate governance, background checks, share purchase agreements, contracts with investors and investee companies, and other such diligence is driven by the fund manager and the fund’s internal team. In many cases IC members may not have access to all such documents as this does not entail their job description.

A few fund managers, however, believe that this brings in accountability among IC members in a manner similar to that of people who are on boards of a listed company. Gopal Srinivasan, chairman and managing director at TVS Capital, mentions ‘prakarna’ (context) to discuss why Sebi must have come up with this regulation. He says, “The formal decision-making power is delegated to the IC and it does not rely solely with the fund manager. Sebi is saying that if you give this power to the external body, they need to be accountable.”

Indian real estate funds are a case in example, where multiple investors have lost money over the last decade, with multiple ongoing legal cases across courts in India. “While Sebi’s intention under the amended regulation is to fix accountability for investments, it may have inadvertently sparked an exodus from the IC as talented persons may now be reluctant to take up IC positions, thereby diluting the robustness of the investment operation,” says Adhitya Srinivasan, of-counsel at law firm Touchstone Partners.

Another real estate fund manager who heads more than Rs4,000 crore in assets under management, and did not wish to be identified, says, “If you look at the returns of either vintage funds or the ones over last five years, very few have delivered returns, especially sector focus ones like real estate. And till now there was no one who was accountable for the underperformance of the fund’s performance. This will make the investment decision makers be more cautious about what they are doing and we have informed all our IC members and none of them have left us.”

Globally, individual IC members are not liable under the securities law, although individual contracts can have these clauses. A fund manager mentions that his firm offers Rs1 lakh per sitting to each of its IC members and they meet around six times a year. Fees vary for each fund, but what could be the penalty that comes along if someone actually files a case against the members? Srinivasan says that Sebi may look to apply specific penalties for non-compliance, and there is at least a theoretical risk of a fine of upto Rs 25 crore and/or imprisonment.

As IC members will now take greater risk for their decisions, conversations around increased fees has become commonplace. Members are also seeking indemnity covers to safeguard themselves. “The regulator has now identified IC members in AIFs but we think that it wouldn’t be long before it percolates to other categories too like infrastructure investment trusts (InVITs) and real estate investment trust (Reits) which have constituted formal ICs they may also begin to rethink their strategy,” Srinivasan adds.

Sebi has also said that if a fund decides to onboard a new external member in its IC whose name was not disclosed in the fund marketing material, they need to get consent from at least 75 percent investors by value of their investment in the AIF to approve the induction.

“It is virtually unheard of globally wherein a fund requires 75 percent investor approval to bring an IC member on the board. The amended regulations could trigger a paralysis in investment operations as some people would want to resign their IC memberships in light of the new rules and new members would need to be inducted which will require investor approval, which may or may not be forthcoming,” Srinivasan adds.

Normally, fund placement documents provide details on the past performance of a fund, investment thesis, future-looking guidance and returns expectations, among others. Usually these documents never mention names of limited partners (LPs), the investors in a fund, their investment size, whether they have a board seat or an observer seat, or the kind of veto clauses they have in a fund. While the move will make it transparent for investors, institutional LPs are wary of such disclosures.

In India, listed companies disclose investment in an AIF in their annual reports without serving too many details. Even endowment funds and pension funds mention them as part of their annual report but family offices and private investment firms never disclose such information.

“The circular says you have to name people who are involved in investment decisions. As one of the key functions of the LP Advisory Committee is to clear conflicts of interest investments, this effectively makes them investment decision makers and they will thus need to be named as such. Institutional LPs will never agree to this and that will create a freeze in terms of capital raising for AIF funds,” says Rehan Yar Khan, Managing Partner at Orios Venture Partners.

While the two-page circular on October 19 created a stir in the ecosystem, Sebi came up with another note on October 22. It stated that the markets regulator has written to the government and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) seeking clarity on the applicability of a certain clause under Foreign Exchange Management (Non-Debt Instruments) Rules, 2019, pertaining to investments in Indian companies by an AIF where the IC includes external members who are non-resident Indians.

Pending clarification, Sebi has said that applications where external members of the IC are resident Indians will be processed, and in cases where IC external members have non-resident Indians will be considered only after receipt of clarifications by the government and RBI. “While it is still open to interpretation, if an external non-resident Indian has veto rights or any other control rights and they govern the decision-making process of the fund, then the fund can be called a foreign-controlled fund and then they will have to adhere to those norms,” says a fund manager who did not wish to be quoted. The manager adds that while many industry bodies are trying to reason with Sebi these new regulations, the market regulator might not be willing to water down the rules.

“The industry body was surprised to see the circular and we are trying to understand if there is grandfathering (implementing rules retrospectively) that may apply. In cases where managers are applying for new funds, it will be put on hold if you have a non-resident member as part of your IC. In this climate, it is extremely onerous and brings uncertainty in terms of capital raising,” says Siddarth Pai, founding partner at 3One4 Capital and co-chair, regulatory affairs committee at IVCA.

He adds that no one is arguing for need for regulations that address their concerns but let us not create unlimited liability for members.