Get, Set, Go: Why Ather Energy is ready to ride the hockey-stick growth

With a new factory, launch of its premium scooter 450X and expansion into several cities, the electric vehicle company is set to move into serious production mode. Positive unit economics have kicked in too, says its co-founders

Tarun Mehta (left) & Swapnil Jain, Co-founders of Ather Energy

Tarun Mehta (left) & Swapnil Jain, Co-founders of Ather Energy

When Ather Energy came out with one of its earlier scooters, Ather 450, the first two-wheeler took a week to fully assemble. By the time the Ather 450X platform came around in 2020, the company was doing 10 scooters per shift in the early mass-production days of that scooter. Today, it can comfortably turn out a 100 scooters in an eight-hour shift, and there is room for more.

If all goes well, especially with India’s struggle with the Covid pandemic, Ather could get to the point where it will have cleared the base of the hockey stick—ready for serious growth. In fact, the company’s performance in the first three months of the current calendar year shows that.

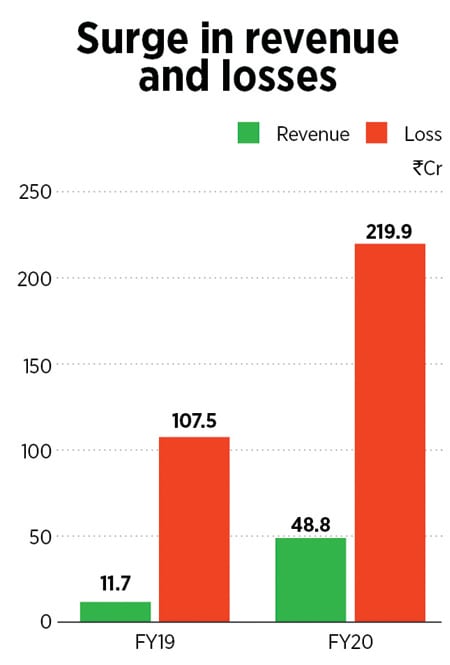

“Just the last month of the last quarter was like one-third of our annual revenue. We saw solid growth,” CEO Tarun Mehta tells Forbes India.

At the end of last year, Ather was present in only two cities—Bengaluru and Chennai—and the company was still selling an older generation of scooter, Ather 450. It moved to the 450X sometime in November and that’s when the product-market-fit clicked and growth got supercharged. From November 2020 to March 2021, retail sales grew roughly 5x, Mehta says, and Benguluru, the company’s most established market, is seeing almost two-and-a-half times as many scooters sold in a month versus November last year.

“Numbers have truly skyrocketed, inquiries are 10x higher, and we are only able to service 20 percent of people who book a test drive, so we are now at a place where essentially the biggest focus of the company is getting more distribution going,” he says.