Heatwaves: A vicious climate change circle

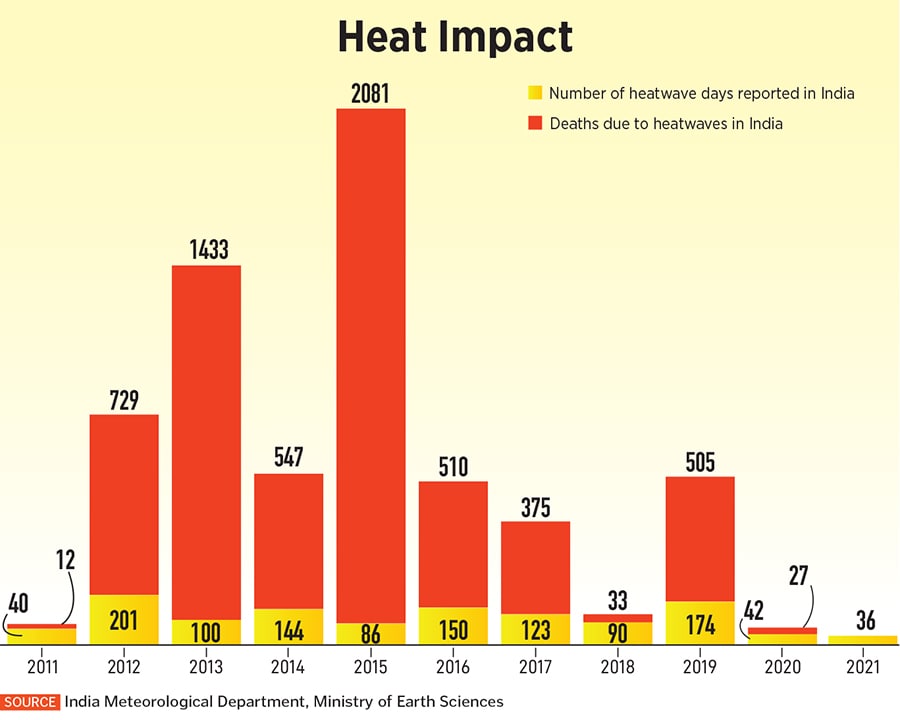

Though heatwaves in India are not a new phenomenon, their frequency and duration have escalated in the past decade. They are not just causing a human crisis, but also an energy and economic crisis

Frequency, length and intensity of heatwaves has increased, while we continue to escalate coal mining and to increase our coal dependence for power

Image: Ahmad Masood/Reuters

Frequency, length and intensity of heatwaves has increased, while we continue to escalate coal mining and to increase our coal dependence for power

Image: Ahmad Masood/Reuters

In Bokaro Steel City, set on the Chota Nagpur Plateau in a coal-rich district of Jharkhand, 55-year-old Jethu Mahto’s work day begins at six in the morning and finishes at two in the afternoon. Mahto has been working in the Bermo Coal Mines for 35 years and continues, even under a punishing sun, amidst a devastating heatwave in one of the hottest areas of India.

The first part of the sixth IPCC report ‘Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis’ released in August 2021 says that in the Indian subcontinent, “Heat extremes have increased while cold extremes have decreased, and these trends will continue over the coming decades.”

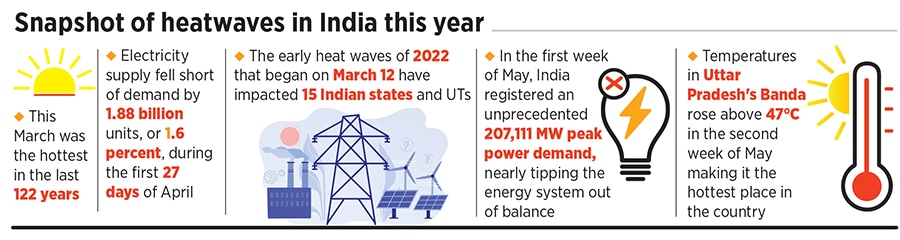

It didn’t take long for India to experience these dire predictions of heat made just a few months ago. In March 2022, even as the second part of the IPCC ‘Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability’ was being released, a series of prolonged heatwaves began unseasonably early, much earlier than normal Indian summer. These heatwaves continue to devastate landscapes and people nearly two months later, showing no signs of abatement.

In Mumbai and Delhi, it’s hotter than we can remember. The worst heatwave in recorded Indian history has us scrambling indoors for the air conditioning and fans. We cannot even imagine the condition of those who toil outdoors, mining coal, exposed directly to unbearable heat.

Besides, the air conditioning we use to combat the worst heatwave in 122 years requires electricity. In India, electricity uses coal; coal is the single greatest contributor to climate change and to the heatwave itself, from its extraction to its burning.