How CEO Aiman Ezzat is positioning Capgemini for its next phase of transformative growth

Ezzat has played a central role in establishing the company's strong base in India and its continued global acquisition strategy. He must now, more than ever, defend his turf from India's IT giants

Image: Joel Saget/ AFP

Image: Joel Saget/ AFP

There was a time when Aiman Ezzat was dropped into the hot seat of CFO at Capgemini, the Paris-headquartered global IT services company.

“I was good with numbers, but I had no finance background. I’d done finance in business school, but that was the limit of my financial experience,” Ezzat, who turns 60 next month, recalls in a recent interview with Forbes India. He had been included in a panel of internal and external candidates and went through a process that would see him become the Chief Financial Officer. It was in December, he recalls, with the end of the fiscal year coming.

Ezzat, who saw himself as an “operations guy,” was thrown in at the deep end straightaway, to close the books for the year, prepare the financial communication that would go out to investors and regulators and also help the then CEO, Paul Hermelin, define the guidance for the coming year.

Would it be a matter of weeks before he was fired, Ezzat had wondered to himself. Then, instead of worrying about knowing everything about finance, he turned the role into one of leadership, and honestly sought out people who knew more than him in specific technical areas.

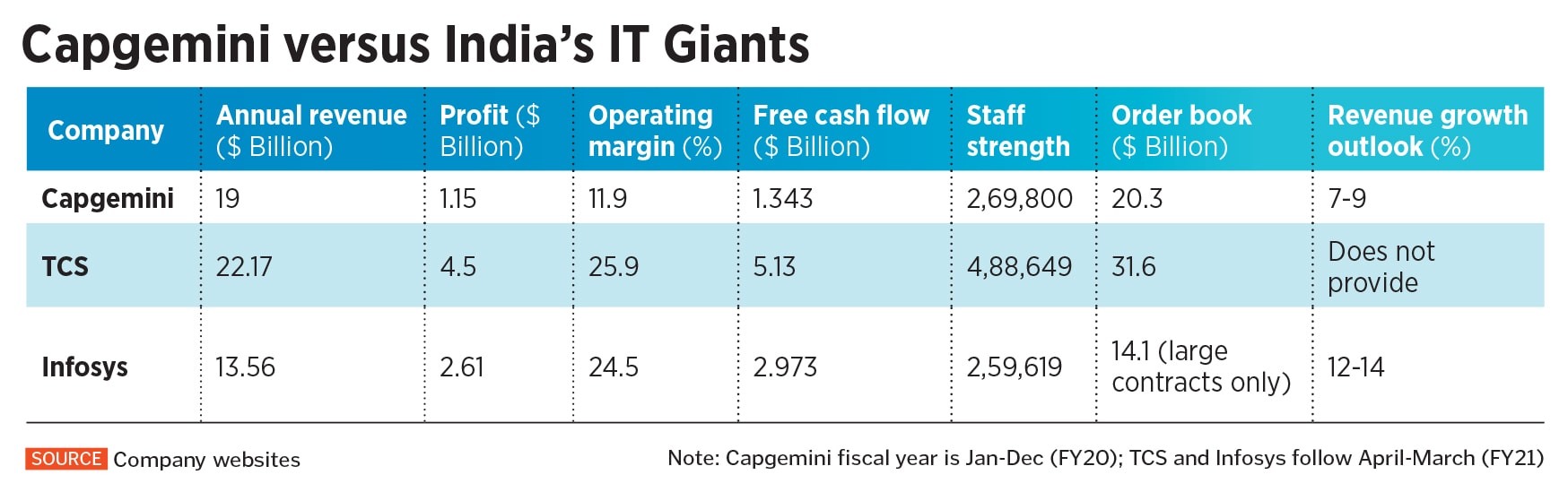

His success in the role over the next six years paved the way for the larger prize. The Chief Operating Officer’s role followed, and in May 2020, after two years as COO, Ezzat was named chief executive of Capgemini Group, a $19 billion technology services provider that offers everything from sophisticated financial services technology to digital twins of complex machinery, full-scale designs of electric and connected vehicles and the plans to manufacture them, migration to the cloud and digital technologies.

Over the last 15 years or more, Ezzat was also instrumental in building Capgemini’s Indian unit that went from a couple of thousand staff to over 46 percent of the 270,000-strong workforce at the company. And, as large corporations around the world boost their technology spending to change their business operations in the post pandemic world, Ezzat expects the Indian unit to play a strong role in innovating for its clients.