How safe are the cars you are driving on Indian roads?

India's speed limits are touching 100km for highways and expressways but safety ratings for passenger vehicles in India are given after conducting crash tests at a maximum speed of 64 kmph

Mohan Savarkar, chief product officer, Tata Motors

Image: Anirudha Karmakar for Forbes India

Mohan Savarkar, chief product officer, Tata Motors

Image: Anirudha Karmakar for Forbes India

Expressways in India have speed limits of 120 kmph for passenger vehicles. Highways have speed limits of 100 kmph. Car speedometers show that the vehicle can be driven at maximum speeds of between 180 kmph and 220 kmph (depending on the car model). But safety ratings for passenger vehicles in India are given after conducting crash tests at a maximum speed of 64 kmph.

There is some rationale behind keeping the speed of crash tests at 64 kmph, as explained by industry veterans later in this article, but the information itself seems to be a footnote—if at all—in the sales pitch that most car buyers get from sales personnel at car showrooms, or even the data sheets available on the websites of rating agencies.

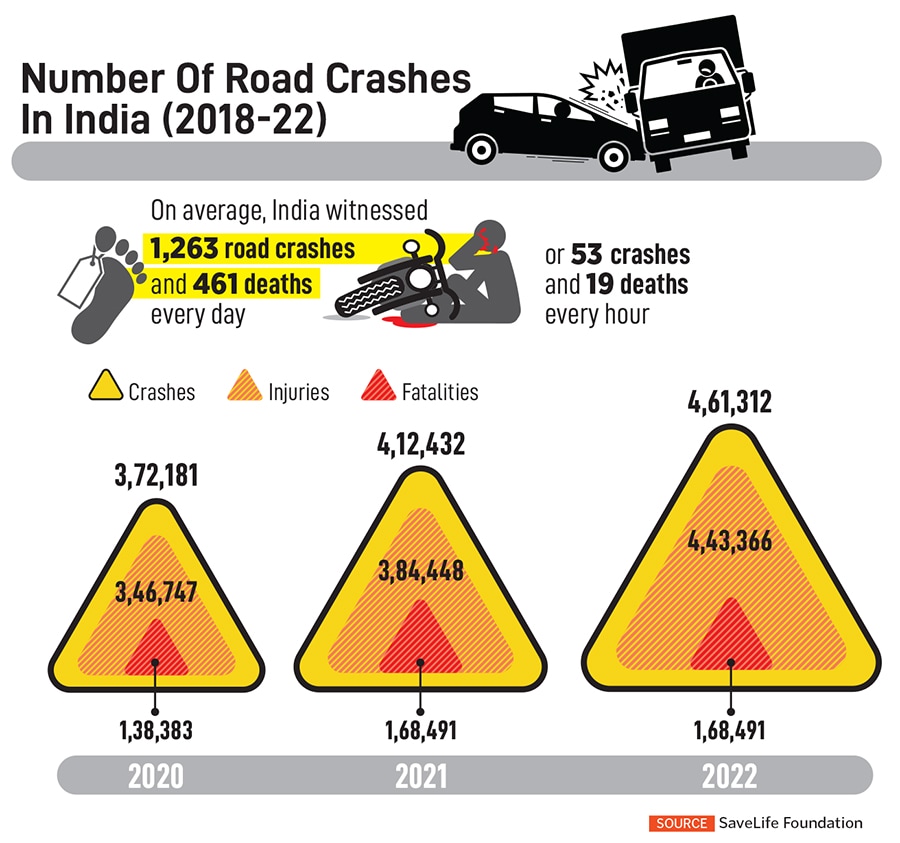

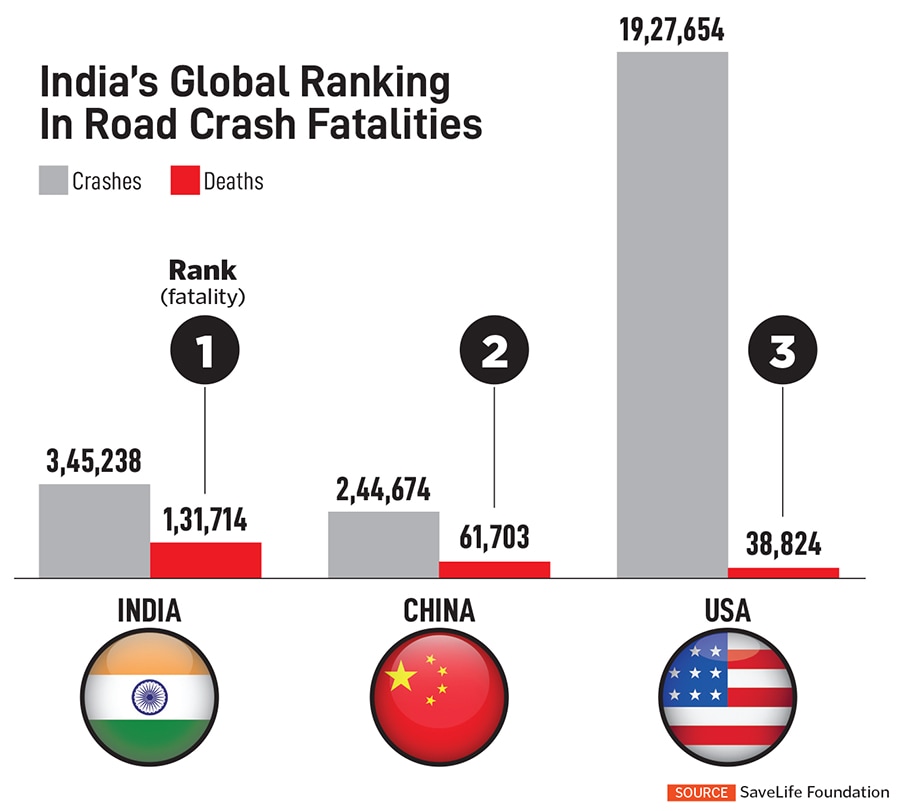

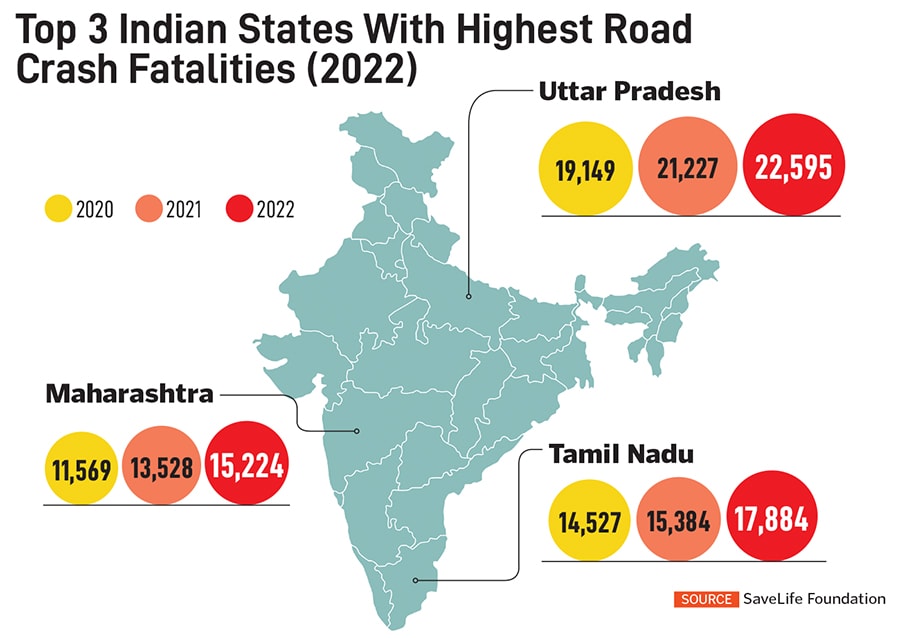

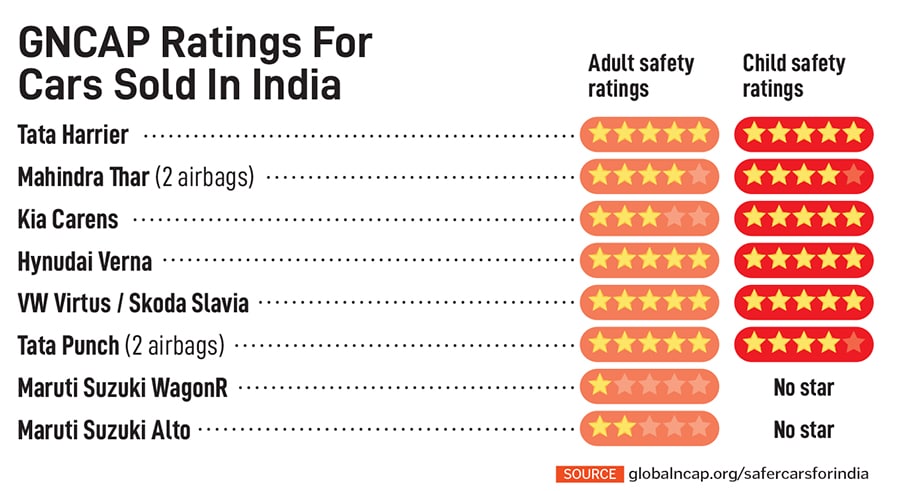

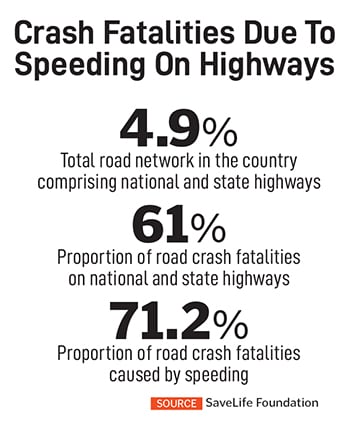

India has the highest number of road crash fatalities in the world (see box), and most of them on national and state highways where drivers were speeding (see box). There is a pressing need to make safety information of vehicles more readily accessible to consumers, while also raising mass awareness about the need to follow driving rules and guidelines in order to avoid crashes, fatalities and injuries.

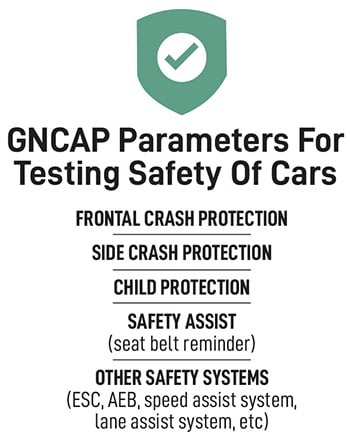

India’s Ministry of Road Transport and Highways introduced the BNCAP (Bharat New Car Assessment Programme) in October 2023, in collaboration with Global NCAP, thus becoming the fifth nation in the world to adopt such a safety system. Although the BNCAP testing parameters are broadly based along the existing GNCAP parameters, there are differences between the two with regard to the rating categories and types of crash tests. Also, GNCAP is a private entity, funded by different car companies and charitable organisations, while BNCAP is a government entity.

(This story appears in the 01 November, 2024 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Tewari further explains that a rear-seat passenger who is not wearing a seat belt is like an 80-kg projectile being hurled at the front seats from behind in the case of a front or rear collision. “This can cause serious injuries not just to the rear passenger, but also to the driver and front passenger,” he adds.

Tewari further explains that a rear-seat passenger who is not wearing a seat belt is like an 80-kg projectile being hurled at the front seats from behind in the case of a front or rear collision. “This can cause serious injuries not just to the rear passenger, but also to the driver and front passenger,” he adds. “Along highways or expressways, there are metal guardrails placed alongside the carriageway,” says Singh. “The point at which the guardrail begins or terminates, the end of the rails are supposed to be covered with a flat sheet of metal, so that no car actually hits the sharp end of the rails, but hits the flat metal surface instead.”

“Along highways or expressways, there are metal guardrails placed alongside the carriageway,” says Singh. “The point at which the guardrail begins or terminates, the end of the rails are supposed to be covered with a flat sheet of metal, so that no car actually hits the sharp end of the rails, but hits the flat metal surface instead.”