Indian space startups ready for take off in 2022

A handful of private space startups have come tantalisingly close to getting their products off the ground. The government's clear intent and support are welcome, but they also need more money to succeed

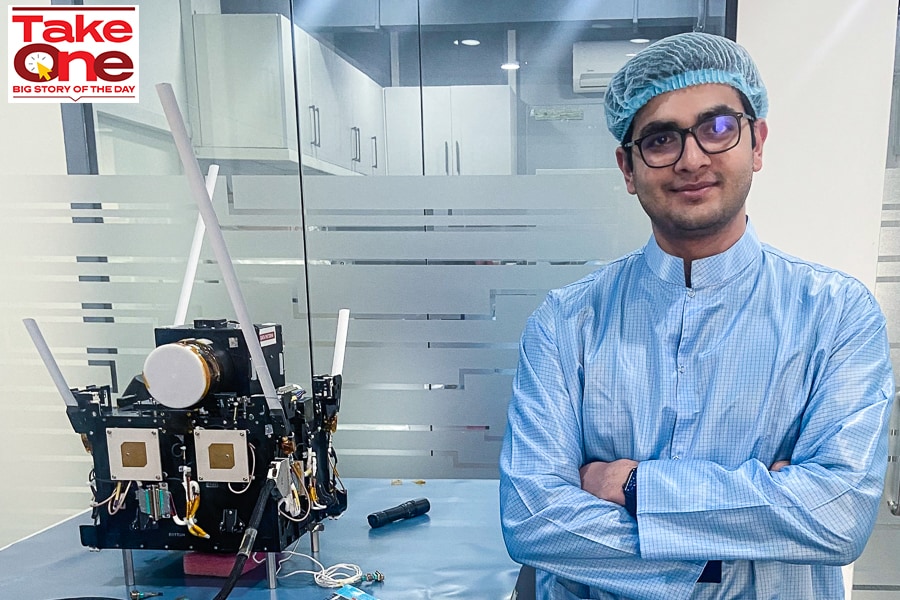

Awais Ahmed of Pixxel

Awais Ahmed of Pixxel

Awais Ahmed has come a long way from the astronomy book, and later a telescope, his father gave him as a schoolboy. If all goes as planned, the first demonstration satellite at Pixxel, the satellite data company that Ahmed and his friend Kshitij Khandelwal started in 2019, will be launched atop an Isro (Indian Space Research Organisation) rocket to an orbit some 500 km above Earth as early as January 2022.

If that satellite—named Anand to honour the memory of a young intern at Pixxel, who passed away later—proves a success, demonstrating the ‘hyper-spectral’ imaging technology that the company has developed, it will help Pixxel push ahead with its plan of putting up a constellation of 36 micro satellites in what are called low-Earth orbits. Typically in the range of 500 to 550 km above Earth.

“The plan is to have a constellation of satellites that can do global coverage on an every day basis so that we are able to see how things are changing daily,” Ahmed tells Forbes India. “In that process, our first satellite has been built, it has been tested, it's ready to launch… we are just waiting for the Isro rocket to get on the launch pad.”

Ahmed hopes that in January 2022, Bengaluru’s Pixxel will be able to send it up. And following that, the plan is to launch the first phase of the constellation before the end of the year, which will help the startup to start serving customers around the world.

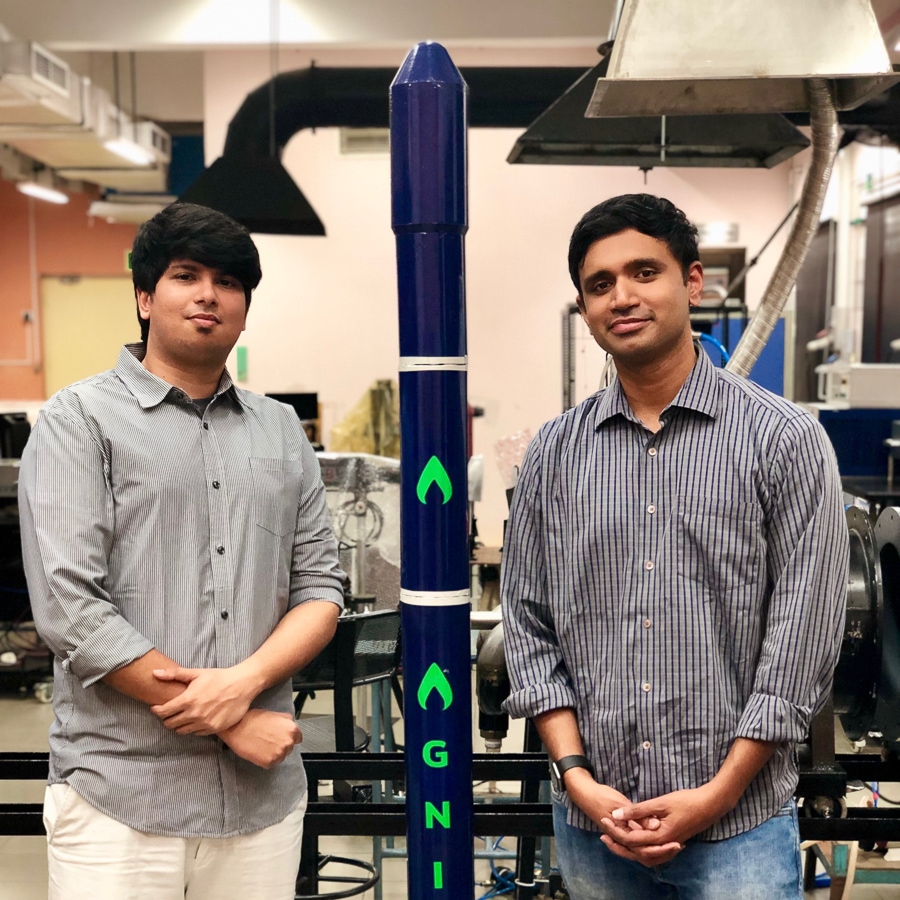

Moin SPM, Co-Founder & COO (L) & Srinath Ravichandran, Co-Founder & CEO, AgniKul Cosmos

Moin SPM, Co-Founder & COO (L) & Srinath Ravichandran, Co-Founder & CEO, AgniKul Cosmos  Today, other well-known investment firms have backed private space startup in India, including Kalaari, which invested in

Today, other well-known investment firms have backed private space startup in India, including Kalaari, which invested in  At a TRL 6, for example—which is a fully functional prototype—a large, established company may be willing to partner a startup to take it to TRL 9 and then commercialise it; and customers might be willing to buy the product.

At a TRL 6, for example—which is a fully functional prototype—a large, established company may be willing to partner a startup to take it to TRL 9 and then commercialise it; and customers might be willing to buy the product.