Inside Mark Kahn's vision to accelerate agri entrepreneurship at Omnivore

Kahn, leading India's best-known agri-focussed venture capital firm, is readying for his third fund, at $150 million, to expand investments into game-changing startups in the sector

Mark Kahn, Managing Partner, Ominvore

Mark Kahn, Managing Partner, Ominvore

Mark Kahn’s exposure to India happened fairly early, growing up in parts of Houston, Texas, where there was a large ABCD (American-Born Confused Desi) community, he jokes. Later as a college student, he had visited India, and in fact a college internship was at ITC’s agri business unit. But the switch to venture capital, backing agri startups in India, wasn’t something he had seen coming, he says.

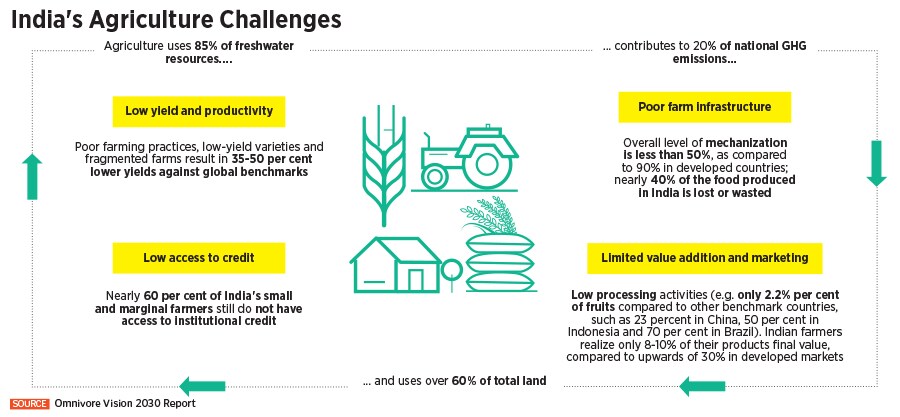

All along, he had expected that he would probably run a large agri-based company, and stints at Syngenta and Godrej Agrovet seemed to be preparing him for that. However, he got frustrated seeing the incremental, and sometimes ineffectual, changes happening in a sector that was 25 percent of the economy and accounted for 50 percent of the country’s population.

He wanted something that would bring step-jump change for the better, to the sector, and improve the lives of the millions of farmers in the country. But, back then, over a decade ago, “If you were an Indian startup and you were focused outside of what was conventional, which in those days was urban consumer or B2B software-as-a-service, you just couldn’t get funding. And we felt that that was insane.”

In 2010, Kahn teamed up with Jinesh Shah, who came from Nexus Venture Partners and really understood the lay of the land in the startup ecosystem, and started Omnivore. Kahn had been working in India from 2007, and the two knew each other because when Kahn was an EVP at Godrej Agrovet, Shah, who was CFO at Nexus, had contacted him while studying the agri business sector in India.

“Despite our personalities being very different, we really hit it off and decided to work together,” Kahn, 42, recalls.

One of the problems that Omnivore set out to tackle is to try and radically increase the profitability of farmers

One of the problems that Omnivore set out to tackle is to try and radically increase the profitability of farmers

Investors like Kahn are seeing many more platforms and marketplaces with embedded fintech and the ability to build much more full-stack models, meaning bringing internet-led services spanning the supply chain — from inputs to finance to market access

Investors like Kahn are seeing many more platforms and marketplaces with embedded fintech and the ability to build much more full-stack models, meaning bringing internet-led services spanning the supply chain — from inputs to finance to market access