Inside the reshaping of CSR in India during Covid-19

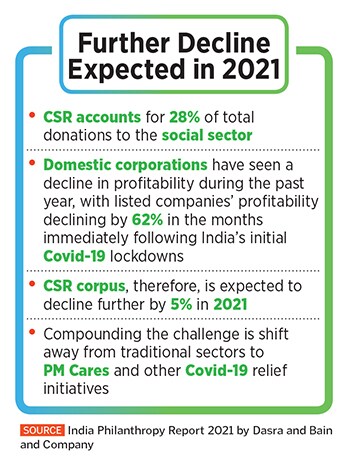

With the recent amendments to CSR rules, a gruesome second coronavirus wave and reduced corporate performance due to the pandemic, social responsibility spend for companies is not going to be the same this fiscal

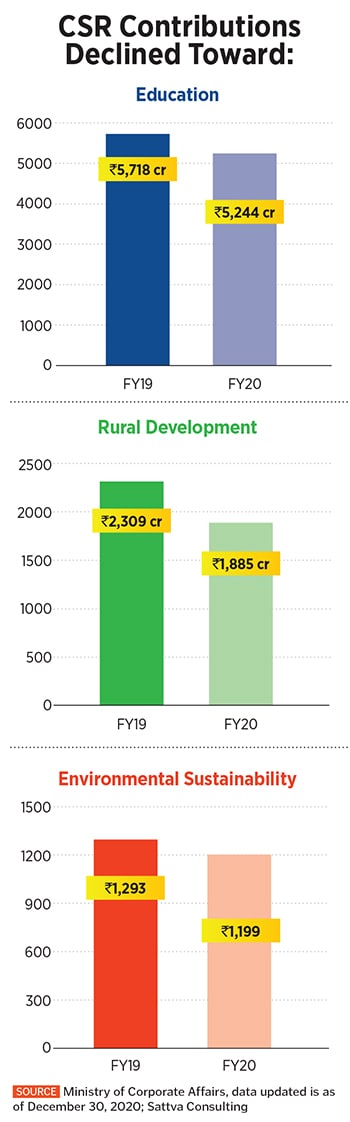

CSR expenditure on education reduced from Rs5,718 crore in FY19 to Rs5,244 in FY20. The pandemic has affected company profitability, which in turn has impacted overall CSR giving. Representative image of the RG Halli government school in Bengaluru

; Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan

CSR expenditure on education reduced from Rs5,718 crore in FY19 to Rs5,244 in FY20. The pandemic has affected company profitability, which in turn has impacted overall CSR giving. Representative image of the RG Halli government school in Bengaluru

; Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan

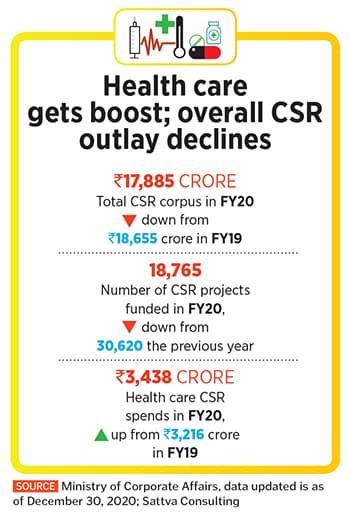

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has been evolving ever since India became the first country in the world to legally mandate it in 2014. A number of recent developments in 2021, as India finds itself in the midst of the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, has set the stage for major shifts in the way companies view social responsibility and work with the social sector.

In the wake of urgent emerging health care requirements, as India pushes over four lakh Covid-19 cases every day, the ministry of corporate affairs (MCA) has been issuing multiple clarifications on what companies could consider as part of their CSR expenditure. The most recent, on May 5, was the announcement that companies could use CSR funds for “creating health infrastructure for Covid-19 care, establishment of medical oxygen and storage plants, manufacturing and supply of oxygen concentrators, ventilators, cylinders and other medical equipment for countering Covid-19”.

This comes on the heels of another clarification on April 22, when the government had clarified that CSR funds could be used to set up “makeshift hospitals and temporary Covid care facilities”. The purpose of these new clarifications, according to experts, is to help companies with compliance as they finalise their CSR budgets for the current financial year in the coming months.

Corporates in India, as they draw up their CSR budgets this year, are trying to strike a balance between taking stock of emerging health care requirements and their traditional social focus areas.

Sudha Murty, chairperson of the Infosys Foundation, tells Forbes India that outlays for the coming financial year will be prioritised around Covid-19 relief, followed by the construction of infrastructure for the Bengaluru Metro, as the Karnataka state government has given a go-ahead for the project and it provides livelihoods to many workers.

Sudha Murty, chairperson of the Infosys Foundation, tells Forbes India that outlays for the coming financial year will be prioritised around Covid-19 relief, followed by the construction of infrastructure for the Bengaluru Metro, as the Karnataka state government has given a go-ahead for the project and it provides livelihoods to many workers.