Monsoon 2022: Will uneven rains worsen inflation woes?

A failure of the monsoon in the east is likely to impact India's food basket adversely

A file photo of a dried canal in late May in Badokhar village on the outskirts of Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh. A severe heatwave in May had caused drought-like conditions in vast swathes of India's agricultural heartland as the rains that usually arrive before the country's prolonged monsoon season had failed. India is particularly vulnerable to drought as its under-developed agriculture sector is heavily dependent on timely, uninterrupted natural weather cycles for its survival.

Image: Ritesh Shukla/Getty Images

A file photo of a dried canal in late May in Badokhar village on the outskirts of Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh. A severe heatwave in May had caused drought-like conditions in vast swathes of India's agricultural heartland as the rains that usually arrive before the country's prolonged monsoon season had failed. India is particularly vulnerable to drought as its under-developed agriculture sector is heavily dependent on timely, uninterrupted natural weather cycles for its survival.

Image: Ritesh Shukla/Getty Images

In April 2022 there were few indications of a deficient monsoon. Weather forecaster Skymet predicted rains within 98 percent of the average. And the arrival of the first spell in late May pointed to a timely start of the monsoon.

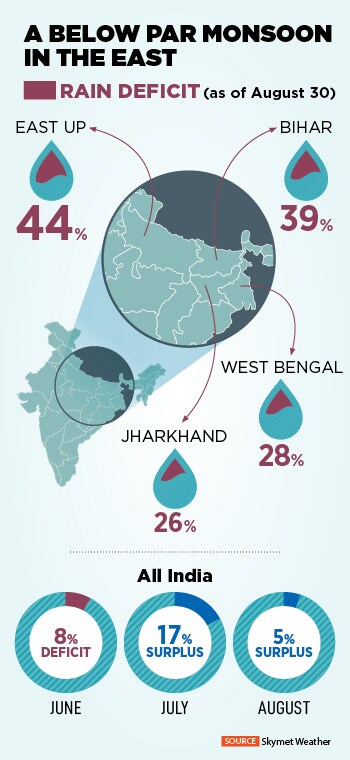

But in the first full month–June–it became clear that the start was not as expected. The country ended the month with an 8 percent shortfall in rains. Pretty soon it became clear that La Nina would have a role to play.

This weather phenomenon results in a lower than normal surface temperature of 3-5 degrees in the eastern equatorial part of the central Pacific Ocean affecting multiple weather patterns across the globe. In India it can result in more rain in the west and south and a deficiency in the east.

So far the monsoon has played out according to this script.

According to G P Sharma, president, meteorology, at Skymet Weather, July and August were excellent months and saw a surplus of 17 percent and 5 percent respectively.

“As of July, retail rice price inflation rose 9.3 percent y-o-y and we see risks of a further rise. Together with higher wheat prices—due to the heatwave—higher cereal price inflation could offset the disinflationary forces from lower global commodity prices,” it adds. Nomura’s economists expect headline inflation to remain sticky above 6 percent until February 2023.

“As of July, retail rice price inflation rose 9.3 percent y-o-y and we see risks of a further rise. Together with higher wheat prices—due to the heatwave—higher cereal price inflation could offset the disinflationary forces from lower global commodity prices,” it adds. Nomura’s economists expect headline inflation to remain sticky above 6 percent until February 2023.