Noise Pollution: When will the government wake up?

Despite the well-established adverse effects of noise pollution on human health and life, widespread breach of decibel levels continues unabated

In Mumbai, noise barriers are mandated under the Development Control Rules at all new flyovers, to protect residents from traffic noise. Similar barriers can be used at construction sites too. However, BMC building permissions are given without mitigation measures even though protecting health and environment are primary responsibilities of Government.

Image: Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg via Getty Images

In Mumbai, noise barriers are mandated under the Development Control Rules at all new flyovers, to protect residents from traffic noise. Similar barriers can be used at construction sites too. However, BMC building permissions are given without mitigation measures even though protecting health and environment are primary responsibilities of Government.

Image: Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg via Getty Images

In Mumbai, a luxury skyscraper coming up next door digs deep into the bedrock. Metal crushes rock, even while under-construction buildings like this one advertise happy children, blue skies and birdsong. The advertisements say nothing of those who live in here and now of this to-be-utopia, forced to bear the health effects and disruption to their lives of noise pollution for months or years.

In March 2022, newly-appointed Mumbai Police Commissioner Sanjay Pandey invited complaints on his own Whatsapp number. Among the first things he discovered was the serious impact of noise pollution on people. Within days of taking office, at his very first weekly Facebook live chat, he announced construction would not be permitted at night and on Sundays.

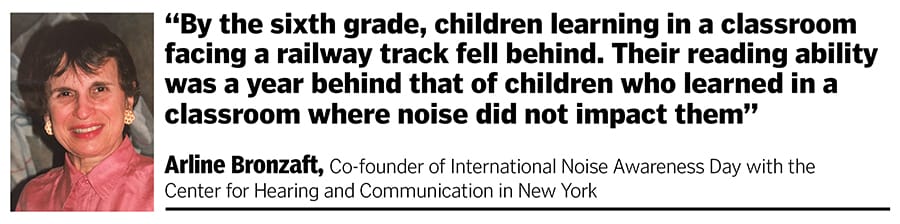

The commissioner’s discovery of ordinary people’s distress with noise pollution is not a surprise. Forty-seven years ago, in 1975, New York-based environmental psychologist Arline Bronzaft studied the effects of noise on learning in children. In a Zoom call from New York, she told me: “My study clearly showed that, by the sixth grade, children learning in a classroom facing a railway track fell behind. Their reading ability was fully a year behind the reading abilities of children who learned in a classroom where noise did not impact them.”

In Mumbai, many schools and colleges are placed next to construction sites and other noise sources. In the last two years during Covid-19 lockdowns and afterwards, ‘work from home’ has become routine and some classes continue to be held online.

Pandey’s action to control noise has the ability to provide relief to people’s daily lives and bring in long-lasting systemic change. To effectively support him, we need to make our voices heard and to complain effectively against all types of noise, including the ‘unavoidable’ construction noise.