Rising inflation could stand in the way of India's economic recovery

If inflation proves to be sticky, rising costs of capital for the government, companies and individuals could also restrict infrastructure spending and slow down private sector capex cycle

Image credit: Amit Dave / Reuters

As India emerges from the Covid-19 pandemic, rising inflation expectations have resulted in a slow uptick in borrowing costs for the government and companies alike. While these are still early days, the next year will be crucial in determining how India’s inflation trajectory progresses. Policy makers are clear they would like to avoid a repeat of a 2011-13 situation when high inflation and low growth derailed the India growth story.

As the pandemic progressed, the government had been careful in its fiscal support for the economy. Much of the Rs 20 lakh crore stimulus package it announced in May 2020 was in the form of food support and credit guarantees. The result was a manageable 9.5 percent fiscal deficit for the year ending March 2021 that included central, state and government enterprises borrowing. “To be fair, the central bank managed that borrowing with no disruption in the bond market,” says Ananth Narayan, associate professor of finance, SP Jain Institute of Management and Research.

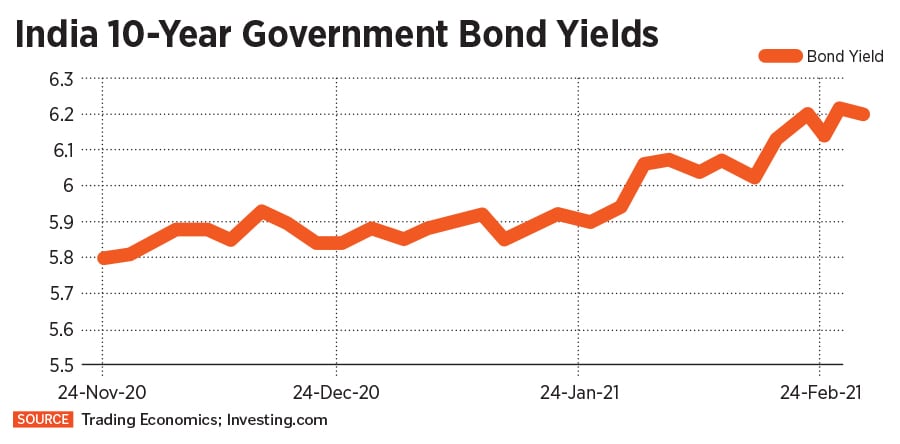

While 2020 went by without any major disruptions, it was the additional borrowing requirements announced in the Union Budget that caught the market by surprise. It included an additional Rs 80,000 crore in borrowing for February and March. This sent the 10 year Government of India bond from 6 percent to 6.2 percent, raising the cost of capital. In two bond auctions post the Budget, the RBI had to intervene to keep bond yields from moving even higher. The government also pushed back the fiscal glide path and indicated that it would bring down the fiscal deficit from a projected 6.8 percent in FY22 to 4.5 percent in FY26. The expectation had been for 3 percent.